We are all in the jungle

Klingenberg

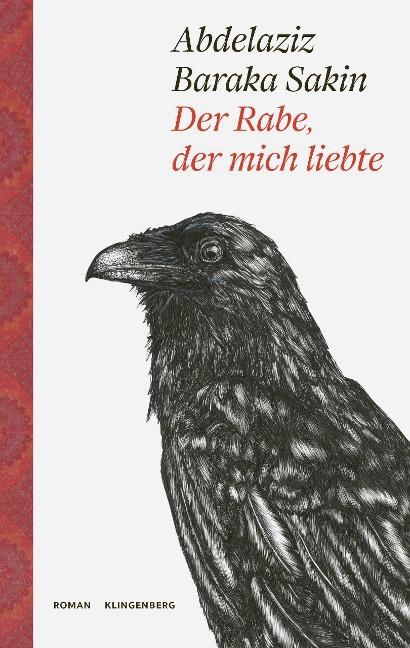

KlingenbergAbdelraziz Baraka Sakin | Der Rabe, der mich liebte | Translated from the Arabic by Larissa Bender | Klingenberg | 136 pages | 21.90 EUR

Abdelaziz Baraka Sakin is one of Sudan’s great authors, known for tackling topical political issues. Recently, another Sudanese author, Leila Aboulela, brought attention to Sakin's novel The Messiah of Darfur (published in 2012 and translated into German in 2021), in Literature.Review to better understand the current situation in Sudan.

Sakin's new novel The Raven Who Loved Me is also a topical, highly political book. Unlike in The Messiah of Darfur, however, Sakin does not focus on the events in his homeland, but on the people who, as a result, have been uprooted and have made their way across borders. This may sound like a well-trodden literary path, as so-called migration literature on arriving and surviving in the diaspora is no longer new territory for writers and has been impressively differentiated: staying in the Sudanese cultural sphere and with the aforementioned Aboulela alone, is her passionate reflection on migration Minarett (2020) for example. With internal migration now also gaining literary significance, as in Abi Daré's great novel The Girl with the Louding Voice, this is even more so the case.

However, Sakin is unusual. This is partly due to the fact that he used his residency as Writer of the city of Graz (2022/23) to craft not only a tender and sombre memorial to the city of Graz in his novel, but also incorporated the experiences of his own years of exile in Saalfelden and Montpellier.

The real surprise is how Sakin transforms these experiences - and his knowledge of migration flows such as the "ant trail" from Sudan via Graz to Calais - into literature. The story of two friends who travel west together, only one of whom is lucky enough to actually arrive, could have been tough, realistic fiction that unequivocally condemns the injustice of the world. But Sakin opts for something completely different. In just 136 pages, he develops a multi-perspective tale that relates the vagaries of life with black humor, and the fateful tragedy that causes Adam, the literary gifted friend, to fail and Nuri, the business traveller, to reach his destination. However, despite all the tender humor and the dizzying moments of a failed escape across the canal at the end, Sakin still manages to weave a dense psychological web, with his hints at early childhood trauma or Adam's schizoid disposition, and his manic obsession with Edgar Allan Poe and his ravens. The whole is a treasure trove of indigenous education too, explained in important footnotes by Larissa Bender, who is responsible for the smooth translation from Arabic into German.

And there is something else that is captivating about Sakin's novel. The ethnographic quality. The psychological profiles of the two friends alone are enough to confirm everything that Hein de Haas recently wrote in his intelligent book on migration, but the other characters who sneak into Sakin's novel through unexpected back doors also tell of migrants (and, of course, European indigenous people) who don’t correspond to popular belief at all. They are thwarted professors, businessmen and blacksmiths who, in their need, become smugglers, finding a livelihood in the jungle of the underground and, of course, always supporting an economy that needs these people, while populist politics portray the opposite. But here, too, Sakin refuses to complain, instead raising his hand, his only weapons humour and a finely honed self-irony, and knows how to tell of a fulfilled life even beyond death, because he knows: "Every side has its dramas and losses. We are all in the jungle."