Stupid yet still madly brilliant

ACTES SUD

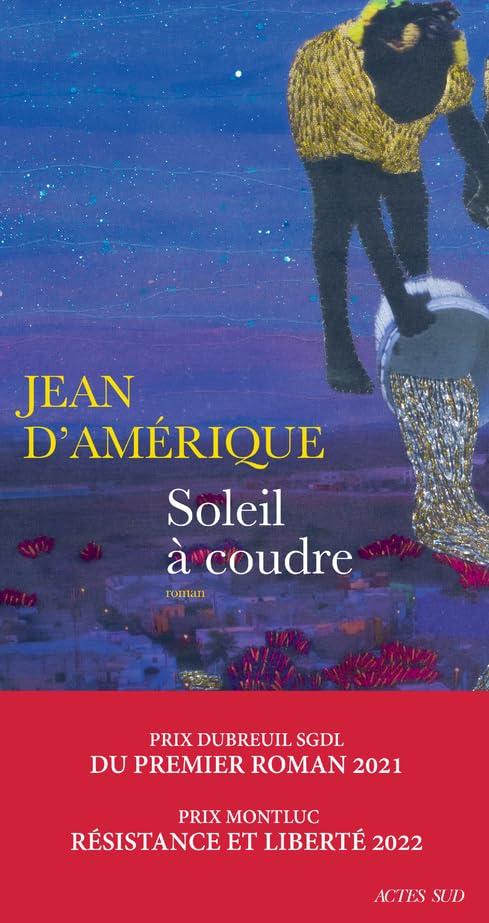

ACTES SUDJean D’Amérique | Soleil à coudre | ACTES SUD | 144 pages | 16 EUR

If, after reading our articles on the Haitian diaspora in the USA by Erica Joseph or the violent deportations of Haitians from the Dominican Republic by Jhak Valcourt, you have wondered why this desperate Haitian diaspora exists at all, you must read Jean D'Amérique's novel A Sun to be Sewn. This slim, 144-page novel is the debut prose novel of the Paris-based, multi-award-winning poet, playwright and rapper.

In language that is by turn intense, sprawling and always poetic, the author describes the coming-of-age of 12-year-old Tête Fêlée, (meaning "cracked head"). And like the name, the language in which the young narrator tells of her life in the slums of Port-au-Prince is also an "allegory of a thousand and one sorrows of the ghetto":

"My search for the symphony of life is running aground. Because of my shipwrecked voice, my breath echoes from now on in a muddy spiral. Strange discord. My name is a poem from the end of the world. Corrosive embers hold the edges of my life captive, consuming me to my core."

In this short book, D'Amérique allows his heroine - and this she absolutely is - to achieve great form and, above all, self-empowerment. This happens not only at plot level, however, in her emancipation from her father, who is part of one of Port-au-Prince's notorious gangs, and at school in the face of an abusive teacher, but she also finds a surprising and tragic fulfillment in sexuality. But despite the sometimes bizarre life of slum and school, it is above all language that stands out, monolith-like, as the driving force of the young Tête Fêlée's self-empowerment. Like the Nigerian heroine of the same age in Abi Daré's magnificent novel The Girl with the Louding Voice, it is the language in Jean D'Amérique's fascinating prose that helps his heroine endure everyday life and ultimately to fight back and take the step that so many Haitians take. This is all the more astonishing as she lives in an environment full of hostililty to this very language, especially from her father: "He hates anything that, in his opinion, doesn't flex his muscles enough. For example, he can't stand literature. Writing would be a physical insult to him. He is not the kind of person who opens himself up to poetry. Poets have huge fists: he would swallow Bernard Lavilliers like a disgusting syrup for this verse. He has no sense of words."

That Tête Fêlée has these words may seem like a miracle to some, like a weird fantasy, but if we think, for example, of the childhood of the South African Nobel Prize winner for literature, J. M. Coetzee, we know that even in the most uneducated households, miracles as well as words can flourish. And Tête Fêlée also knows these miracles, since she is familiar with one of the great classics of modern French literature, Romain Gary's The Life Before Us. And she also knows, of course, that the Cité de Dieu in Port-au-Prince is not Belleville in Paris:

"Here you see cheeks on which poverty stares, meet bursting gazes, yawning abysses of eyes, idle chatterboxes, miles of bread, education and food exile, see the children who have no prospect of sunshine, crawl around in the shadows of violence, becoming gangsters, to shoot each other later, this strangling air, feels the relentless decay during the times of epidemics, in which one must look out for a ray of light, eternal downward spiral, dream-shattering land, in addition to the perishing youth and the women who march silently over the wounds...."

D'Amérique recounts all of this in his short, wonderful but cruel novel and, at the end, we stand before this literary chaos, completely amazed and delighted. Partly because it is simply hard to believe that so much can be told in so few words. It is also perhaps due to the delicate subtext around his heroine that D'Amérique weaves into his prose. Because in memory of Carson McCullers, Tête Fêlée recognises that it is ultimately this wonderful melancholy that makes life bearable for us, a life that can be "both stupid and sometimes madly brilliant".