Kafka three ways

The greatest happiness is when it is very small.

That's why, if I had to write down my life,

I would only note little things.

How happy it makes me,

to see how you hold your wine glass.

Or how you tie your shoes.

Or just to feel

how you run your hand through my hair.

I believe that the glory of life

always lies ready in all its fullness.

But hidden, invisible in the depths.

If you call it by the right name,

then it comes.

The quote comes from Kafka's diaries. You hear it as an off-screen commentary during the credits. It also appears in Michael Kumpfmüller's novel, on which the film was based.

Michael Kumpfmüller | The Glory of Life | Kiepenheuer&Witsch | 240 pages | 23 EUR

When the novel was published in 2011, it was met with curiosity and skepticism. Kafka was considered a tragic character who suffered under his tyrannical father and was never able to fully emancipate himself from his family. He had neither a stable, happy relationship nor a profession that fulfilled him. He retired at the age of 39 due to incurable pulmonary tuberculosis. Kafka's only passion was literature, but he also found writing difficult and was rarely satisfied with the few texts he completed. On his deathbed, he asked his best friend, Max Brod, to burn them all.

Can the last year of the life of a terminally ill, neurotic writer, who became famous for his descriptions of feelings of guilt, absurdity, hopelessness and overpowering bureaucracy, be credibly told as a happy love story?

Yes, it can, and with what a result! Michael Kumpfmüller has proven this magnificently. His clear style creates a fascination, an identification and a magnetic pull. The novel describes with precision events and impressions both positive and negative, alternating between Franz's and Dora's perspective. There is also an abundance of detail - tiny, sensual details, similar to those in the quote from Kafka.

When the novel begins, Franz is already balancing on the precipice of death. Dora has no choice but to keep him company on this cliff-edge. Nevertheless, their year together is shaped by the love that develops between them. But also by inner doubts, economic and health problems, as well as rigid social conventions and prejudices. They had an age difference of 15 years. Neither of them were completely "free", but "more or less" in a relationship. Dora did not have easy access to Kafka's work. Kafka's integrated Jewish family rejected religious, Jewish "penniless refugees from the East". Dora came from a religious, impoverished Polish-Jewish family. Her father, in turn, refused to give Franz permission to marry Dora as he was not a practising Jew. Without this permission, he was not prepared - as he had been with his previous three engagements - to marry Dora. Added to this, Kafka's health was steadily deteriorating; there was inflation and the flaring up of anti-Semitism in Berlin during the Weimar Republic; Dora's disappointment because Franz and his family would not stand by her, while she was prepared to give everything for their relationship. The list goes on..... or we could sum it up thus : That's life.

The novel's tour de force is describing this reality, as well as the wonderful love between these two complex characters, in a clear and non-judgemental way. Happiness and unhappiness are balanced. A promising prerequisite for an adaptation. However, it is clear that a feature film that fills an evening cannot achieve the wealth of detail and complexity of a novel several hundred pages long.

The film adaptation is reminiscent of a filmed poetry album with best-of quotes

What did the screenwriters (Michael Gutmann and Georg Maas, also director) make of this love in the face of adversity? Which cinematic solutions did they choose for the love and which for the adversity? Which motifs did they cut, which did they shorten, which did they give space to?

The Glory of Life | DEU/AUT 2024 | 99 minutes

It is striking that the screenwriters removed, shortened or anecdotally trivialized much that was negative, problematic or ambivalent.

The biggest change is the transformation of two extraordinary people into two very ordinary people. Their meeting and their relationship are told through standard scenes, like those in the guidebook, Romance for Dummies: Dora and Franz play string games on a bench overlooking the sea. They walk barefoot on the beach. Little waves wash over their feet. Franz takes up Dora's idea of plunging into the sea in his underwear (with tuberculosis!?). Franz picks Dora up for their date on a roaring motorcycle. The sun shines brightly over everything. Dora teaches Franz some dance steps. Franz buys Dora a bouquet of flowers with an advance from his publishers.

Did Kafka really ostentatiously throw his manuscripts into the oven in front of Dora's eyes? So that she has to ask, what on earth are you doing ? The wishful thinking of every Kafka fan is that he was less theatrical, and had ,in fact, burned them in secret.

The children from poor Jewish families that Dora looks after in a spa house on the Baltic Sea are all sweet and well-behaved. Almost geeky, in fact. No wonder none of the children react naturally after Kafka tells his fable about the unlucky mouse that is eaten by the cat. It would have been interesting to give reality a tiny chance. If at least one child had said: I don't understand. Or: Cats are stupid. Instead of that, the death of the mouse turns all the children into Kafka fans. Speaking of children - why do they always look like they've been cast in films? Because they are cast, of course. But couldn't you tell a casting agency for a change: we want children who look like real children. Not like they came from a catalogue of models. I'm sure the casting agencies would be happy to do that.

Max Brod, the best friend, is not a writer, hedonistic womanizer, adulterer and puller of strings as in reality and as in Michael Kumpfmüller's novel. Instead, he is an uncomplicated, cheerful character, always with a smile on his face. He provides comfort and spreads good humour. How does he manage that? He pours champagne and tinkles jaunty melodies on the piano.

This list of scenes forged from the sentiment 'Life is beautiful - for all those who believe in the stork' could go on, but the principle is clear. Such naive notions of happiness and reality are reminiscent of kitsch love stories and feel-good films.

The message from directing duo Georg Maas and Judith Kaufmann seems to be this : that happiness in life comprises blocking out the negative. According to their smooth, clean images, a wonderful life means: a life in an advert - The sea is beautiful. The sky is blue. Children are sweet. Outside, the sun is shining. Inside, everything comes from the Manufactum catalog. (Claim: good things still exist). That would mean we should say goodbye to personal nooks and crannies. Instead, we should content ourselves with consuming and dating, like Lieschen Müller and Max Mustermann. Then the glories of life will also work out.

There are more than enough films like this. New ones are coming out all the time. It is almost superfluous to sweeten, colour and rework Kafka's last bittersweet year of life. Why only almost? Because some elements are surprisingly well done despite all the criticism.

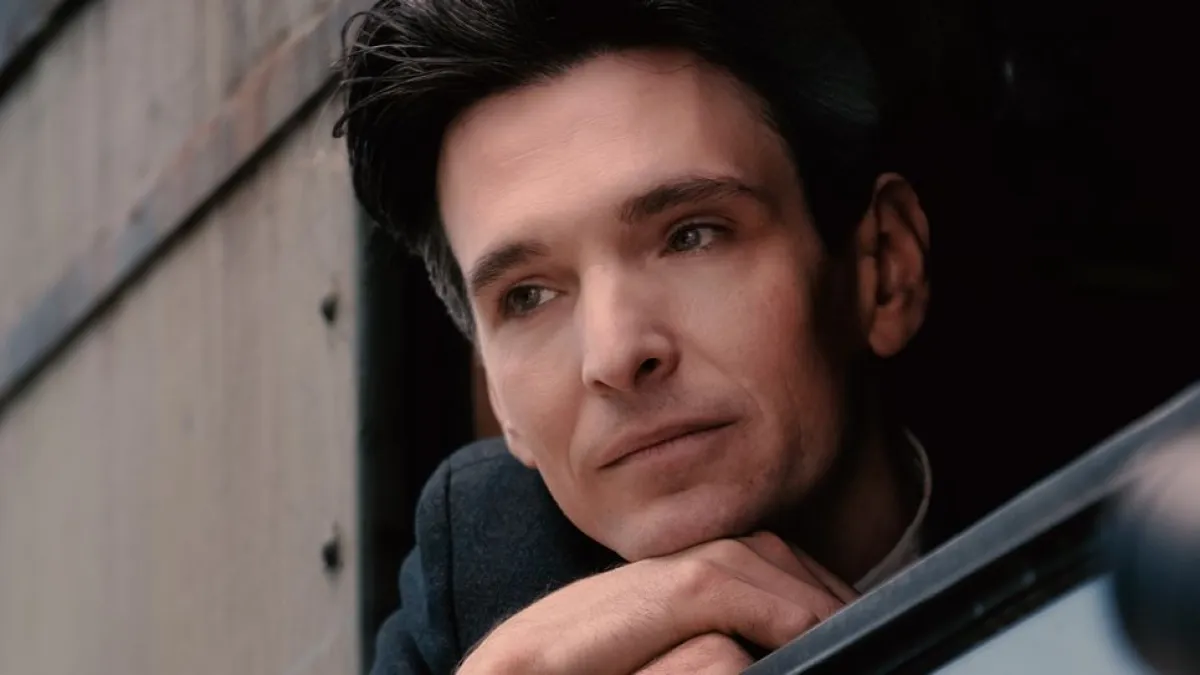

Sabin Tambrea plays Franz Kafka very convincingly. It's as if the aura of his sensitive character hovers over the trivial scenes in the script, especially when he is not speaking fictional dialogue but original quotations. Henriette Confurius is compatible with him as Dora Diamant. It's a shame that the script has reduced her character almost to the point of having no character at all. In reality, a rebellious runaway, self-confident Zionist and communist - in the movie, a self-sacrificing, well-behaved lover.

The best parts are when you listen to Kafka's texts. The film cannot diminish their subtle humour and relevance. On the contrary, the shallow setting really brings out their power. After this film, his work seems even more impressive than it was before.

The series is a brilliant, tragicomic journey through Franz Kafka's life and work

The mini-series Kafka shows that there is another way. However, it is clear that a feature film that fills an evening cannot achieve the wealth of detail and complexity of six episodes.

Reiner Stach | Kafka | S. Fischer | 608 pages | 18 EUR

A comparison is still worthwhile. Daniel Kehlmann wrote the screenplays based on Reiner Stach's three-part biography. The film was directed by David Schalko.

In both cases, the scripts are made up of historical and biographical facts, original quotes and several fictional elements.

Kafka | Miniseries in 6 episodes | David Schalko (director) and Daniel Kehlmann (screenplay)

For example, no one can know what the first words between Franz Kafka and Dora Diamant were on the Baltic Sea beach in Müritz (The Splendor of Life). Or what Kafka chatted about with a prostitute in a Prague brothel (Kafka - The Series).

In the screenplay by Michael Gutmann and Georg Maas, the original quotes are the highlights of the film. In Daniel Kehlmann's series, on the other hand, it is virtually impossible to tell what really happened, what he has reassembled or what detail he has invented. One example is when Franz Kafka is chatting about poems and rhymes with a prostitute during a flirtation. It is unlikely that this happened in a brothel. Or perhaps it did? - With this scene, as with the whole series, the principle is this: it's so seductive that you absolutely want it to be true and to see more of it, whether or not it matches reality.

How does the series manage to make you believe everything and yet be wonderfully surprised even by biographical events that you've heard about umpteen times before? It doesn't even try to give the impression that it is stringing together authenticated facts in the most realistic way possible, like a normal biopic. The exterior and interior locations do not claim to be anything other than studios and backdrops. Sometimes this artificiality is even accentuated.

In contrast, the authenticity, the humour and the personal reflections that Daniel Kehlmann and David Schalko have given Kafka are overwhelmingly real. There are many clichés and platitudes lurking on the path to understanding the writer of the century. Kehlmann and Schalko have found their own, more original ways and means. The screenwriter and director have created, from facts, original quotes and eyewitness accounts, a new reality that is coherent, exciting and seductive. Or, to be precise, several realities that can diverge irritatingly from one another. A great narrator (Michael Maertens) seems to hold the narrative threads in his hand and guide the audience. In this way, they witness how he has to correct himself again and again. Or even how the characters openly contradict the narrator.

The series is not told from Kafka's perspective, but from that of his best friend Max and his three fiancées Felice, Milena and finally Dora, to each of whom a separate episode is dedicated. Another episode focuses on Kafka's family, and another on his work as a lawyer at the Prague Workers' Accident Insurance Institute.

Each of these perspectives shows a new facet of Franz Kafka. His shyness, his feelings of guilt and his fears are well known. The multi-perspective approach also brings out his charm, his quick-wittedness, his emotional cruelty, his emotional coolness, his curiosity and his keen powers of observation, as well as his neurotic quirks, dreams and longings. Actor Joel Basman brilliantly plays Franz Kafka as a humorous rogue, stern critic, loyal friend, highly ambitious writer, anxious son, cowardly lover, pleasure-seeking brothel visitor and vulnerable lover.

Director David Schalko has realized the narrative richness of the screenplays with all the possibilities the medium has to offer. Flashbacks, time jumps, multiple levels of reality, dreams. Characters speak into the camera, address the audience directly.

Despite this exuberant creativity, which is rarely seen on television, you never get the feeling that you're watching an experimental film. On the contrary. The sometimes ironically omniscient, sometimes ironically overwhelmed narrator is followed as enthusiastically as a clever circus director who leads his audience through a breathtaking spectacle.

The multi-perspective approach not only shows different perspectives on Franz Kafka. The people around him have also been impressively portrayed. Normally, the lives of secondary characters are dull. They only have a decorative function, like a salad garnish on a plate in a cheap restaurant. Once they have fulfilled their function, you don't see them again. You don't miss them either.

In this series, however, the fascinating secondary characters shine brightly. Kafka's mother Julie (Marie-Lou Sellem), sisters Ottla (Maresi Riegner), Elli (Mariam Avaliani) and Valli (Naemi Latzer) radiate beyond the scenes in which they appear. Liv Lisa Fries dazzles as Milena Jesenská. It's such a shame that Franz Kafka and Grete Bauer twice broke up, having twice been engaged. Had they married, we could have admired the great Marie-Luise Stocker for longer.

Kafka's father, Herrmann (Nicholas Ofczarek), oscillates between monster, before whose outbursts of rage the family trembles, and victim of his own obsessive character.

The writers Max Brod (David Kross) Felix Weltsch (Robert Stadlober) and the blind Oskar Baum (Tobias Bamborschke) are so humorous that each of their joint appearances becomes a comical feast.

When you see Lars Eidinger as Rainer-Maria Rielke, you wish there was a spin-off about Rainer Maria-Rilke.

The servant in Kafka's parents' house (Blanka Danulek) doesn't even have a proper dialogue. The receptionist at the Askanischer Hof (Anuschka Voss) only speaks a few sentences. Nevertheless, both are so fascinating that you really want to see them again.

Daniel Kehlmann has drawn them all with the greatest precision and artfully exaggerated them. David Schalko has staged these "character extracts" or "character vignettes" with flair and humour.

This eulogy is not over yet. Kehlmann has brought together and interwoven Kafka's life with some of his writings such as The Metamorphosis, The Trial and The Castle. This elegant oscillation between biography and oeuvre is magnificent. It not only makes you want to reread Kafka, or rediscover him. It also reminds us that film and literature are not just for consumption, but that we can and must also be creative with them.

There are many more writers who are worthy of being read, celebrated and filmed with the same delight. It's just a shame that they have to be buried for 100 years first.