Inside the mind of Theresa Nages

dtv

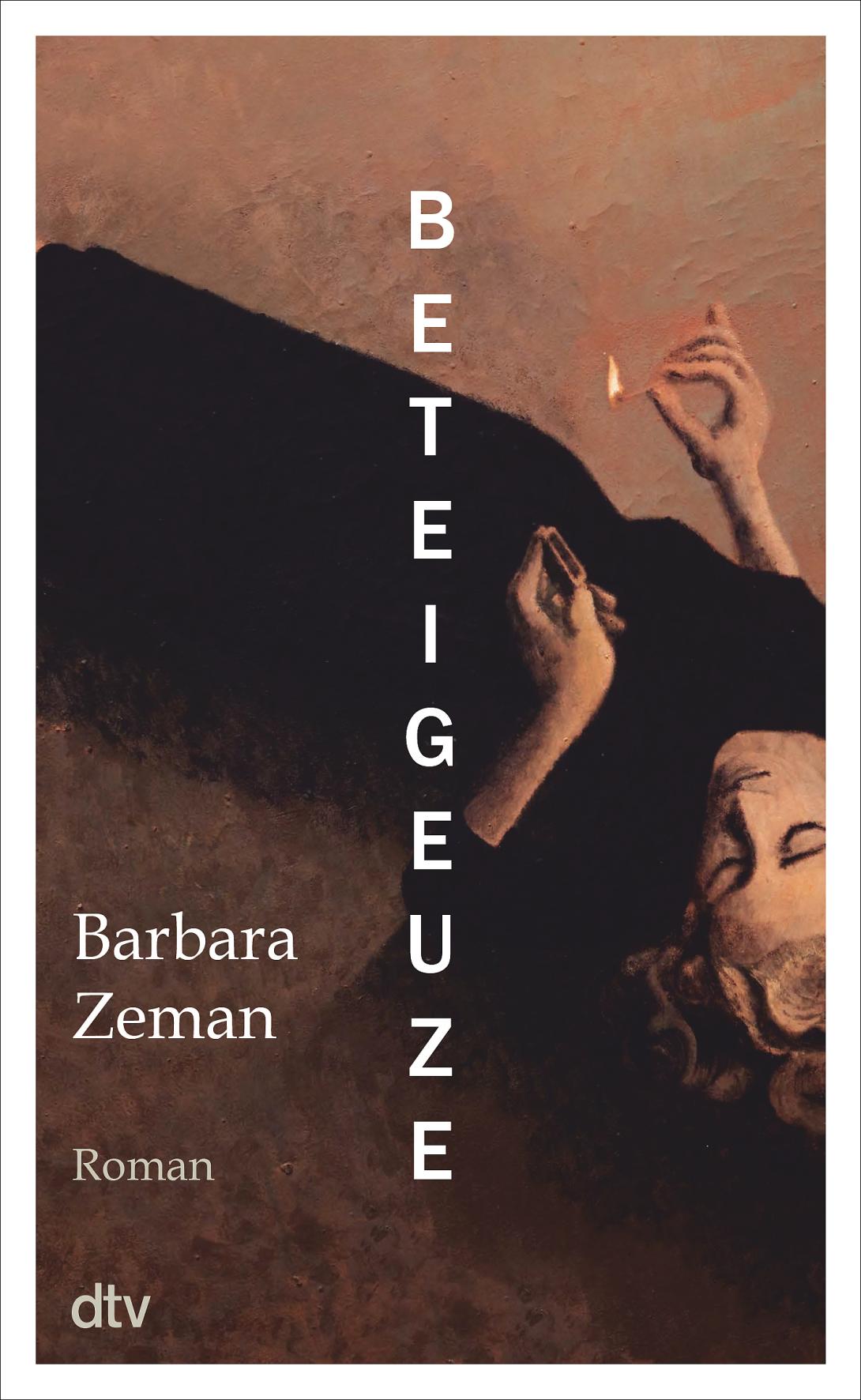

dtvBarbara Zeman | Beteigeuze | dtv | 304 pages | 24 EUR

It is often said that books have to "reach out" to the reader. The title, cover and first sentence should take each reader by the hand and help them "enter" the story. Perhaps in the same way that parents hug their children at nursery before taking them home. Or the way geriatric nurses carefully manoeuvre nursing home residents into wheelchairs to take them to exercise class or bingo.

Anyone seeing the cover of this book - an untitled picture by Swiss painter Lenz Geerk - is neither hugged nor wheeled anywhere. They stand before a small, irritating threshold: a woman in a black dress is lying or perhaps floating, a burning match held between her index finger and thumb. The letters of the title are not juxtaposed horizontally - as is usual - but vertically, recalling the shape of a candle that is about to be lit.

B

E

T

E

I

G

E

U

Z

E

How on earth is that pronounced? What does this word mean? Is it a proper noun? A French meringue? A savoury casserole? Thanks to the internet, a few clicks later we know: "Beteigeuze" is pronounced exactly as it is spelled. The word comes from the Arabic "yad al-ǧauzāʾ", meaning "hand of the giantess". It was distorted in the transcription and refers to a giant star in the constellation of Orion. So far, how mysterious.

The first sentences describe Theresa and Josef's bus journey through good old Europe, on the familiar planet Earth. From Semmering (Austria), via Tarvisio (Slovenia) and Udine (Italy). The author, Barbara Zeman, only needs a handful of short, precise sentences; about the colours of flowers and how the boyfriend of Theresa Neges (the narrator) looks like a dead person when he sleeps. A few pages later and at the end of their day long journey, the couple find themselves in Venice.

Readers, however, sit in awe in Theresa Neges' head. They see with her eyes, smell with her nose, hear with her ears and feel with her skin. Whoever crosses the threshold will be wonderfully seduced, swept away into the heart of Theresa's life.

The forty-year-old fluctuates between depression and euphoria. Appointments with the therapist leave her feeling low. She doesn't take the prescribed psychotropic drug because of its side effects. Theresa tests her limits, fibs, and lies even to herself. Most of the time, the relationship with her boyfriend is wonderful - that is, until her ex shows up and wants to move in with them, when things get dangerously rocky. Contrary to the maxims of the zeitgeist, Theresa doesn't try to optimise herself or her life.

Instead, Theresa savours every moment with passion - whether terrible or beautiful. Holding her breath on the floor of an indoor pool, stumbling from mishap to mishap as a waitress or observing the starry sky. From where the eponymous giant star "Betelgeuse" magically attracts her. Theresa's boundless curiosity soaks up the present, wanders through the past and marvels at tardigrades, tiny creatures that grow no larger than a millimetre.

One of the attractions of good literature has always been that readers can look into the minds of other people. This is also one of the reasons for the wave of success of (auto)biographies, memoirs and self-awareness books. In many cases, what goes on in the minds and books of the authors is similar: coming-of-age stories in which there is more or less whining and a lot of psychologising. Parents, partners, illnesses or turbo-capitalism are always to blame, and all are written with almost interchangeable words and sentences.

Beteigeuze is a far cry from such mass-produced fiction. Theresa Neges is a unique, highly sensitive character whose life Barbara Zeman allows us to participate in almost physically thanks to suggestive, poetic language.

Apropos "sensitive" and "physical" - one of the curiosities of our time is that "health apps" measure, document and analyse our bodies and their activities around the clock. Weight, relaxation and sleep cycles. Blood pressure, pulse, calorie consumption. Oxygen saturation, the female cycle and, of course, every sporting activity. Ironically, such a jumble of numbers and statistics hardly helps us to get to know ourselves better or feel more comfortable in our bodies. Instead, these apps with "ideal values" and "personal goals" only serve to fuel the pressure to compete and perform. And thus the alienation from our bodies and ourselves.

In contrast to this fetish of data collection, Beteigeuze is a triumph of individuality, the senses and sensuality. Barbara Zeman's elegantly precise descriptions of impressions, feelings, self-doubt, desires and dreams create a torrent of reading and sensuality. Her unique sensitivity and rhythmic language inspire us to observe our own lives with the same exuberant curiosity and attention to detail as Theresa Neges, and to live them to the full.