Against "colonial amnesia"

Atlantis

AtlantisMartin R. Dean | Tabak und Schokolade | Atlantis | 224 pages | 22 EUR

In Jorge Luis Borges' short story Funes, el memorioso (Ficciones), a first-person narrator in the 1940s recalls his encounters with Ireneo Funes, who died in 1889 at the age of 21. Funes, paralysed following an accident, has an infallible memory: he remembers every detail, knows "the shapes of the clouds in the south at dawn on April 30th 1882, and can compare them to the veins in the Spanish leather of a book binding that he'd only set eyes on once". (1)

For the Swiss author Martin R. Dean, this short story is of enduring significance. In his debut novel The Hidden Gardens (1982), Dean already establishes a link with the work by quoting the aforementioned sentence about the clouds from April 30, 1882. (2) In Monsieur Fume (!) or The Happiness of Forgetfulness (1998), he resurrects the character as a writer obsessed with clouds. In A Piece of Heaven (2022), he varies the motif again when the main character's friend is paralysed in an accident and is tormented by an excess of memories. Borges' short story remains a point of reference even for Dean's most recent work, something that is evident when you look at Funes, el memorioso from a postcolonial perspective.

Borges' Funes story is initially conceived as an allegory of historiography in general: from a temporal distance, a narrator speaks about a character with absolute memory and exposes the tension between the complete availability of memory and its linguistic representation, always delayed and reshaped. In this way, the fundamental problem of historiographical narration is exposed: it is impossible to remember without being selective, and to report without shaping. However, little attention has been paid so far to the fact that this allegory is set in a colonial context. Funes is explicitly described as "Indian" (3), located in a peripheral province and provided with exoticizing attributes that deprive him of a concrete historical and social place: he is "Zarathustra" (4), "older than Egypt" (5), "monumental as ore". (6) At the same time, he is linguistically disempowered: "I will not attempt", the narrator declares, "to reproduce his words". (7) "I prefer to accurately summarise the many things Ireneo told me." (8) Borges' text therefore also demonstrates how colonial historiography works. The prerogative of interpretation lies with the white, "[i]ntellectual" "city dweller" (9), who reconstructs and shapes memory for the "Indian boy". (10) The colonised person becomes the source, but not the speaking subject. (11)

Hanser

Hanser

Hanser

Hanser

Atlantis

Atlantis

Atlantis

Atlantis

This addresses problem areas, something Dean also tackles in his current collection of essays In the Echo Chambers of the Foreign (2025): mechanisms of stereotyping, selective memory, colonialism. For example, Dean describes how, as the son of a Swiss mother and a father of Indian origin from Trinidad and Tobago, he was exposed to racist prejudice from childhood in his home in Aargau, and how difficult it was to access the history of the non-Swiss branch of the family, which seemed shrouded in silence. As with Borges, this difficulty can be read allegorically: As soon as Dean traces his origins, he discovers "that his [s]mall history is bound up with the great history of colonialism" (12). The family silence thus appears as a symptom of a comprehensive 'colonial amnesia' - an "active forgetting of the connections between Swiss and colonial history". (13) With this concept of 'colonial amnesia', Dean explicitly ties in with postcolonial memory criticism in the wake of Stuart Hall and at the same time contributes to a field of research (14) that has gained considerable momentum in recent years: Recent historical scholarship has focused so strongly on "Swiss links with colonialism" (15) that Georg Kreis was able to present a 200-page research report on the subject in 2023. (16)

Even before historiographical reappraisal gained momentum, Dean had begun his literary remembrance work, tracing Swiss colonial implications in Der Guyanaknoten (1994) and Meine Väter (2003). His most recent novel Tobacco and Chocolate (2024), conceived as an autofictional memoir project, remains indebted to Funes, el memorioso insofar as Borges' short story - according to the editor's fiction in Ficciones - is intended to be part of a volume of memories. While the narrator of Funes, el memorioso remains solely dependent on his not infallible memory, the protagonist of Tobacco and Chocolate taps into memory via various other mechanisms. Three of these will now be explored: photographs as media memory triggers, food and luxury goods as indicators of neo-colonial ties and human bodies as archives of transgenerational trauma. In the novel, all three activate memory processes that prevent colonial history from being forgotten.

Photographs

The novel Tabak und Schokolade begins with the death of the protagonist's mother. The biography of this protagonist largely coincides with that of Dean. Born in 1955, he spent the first five years of his life in Trinidad, which at the time was still "firmly in British hands" (17). After his mother separated from his father, she returned to Switzerland with her son, where she remarried - again to a Caribbean man of Indian origin.

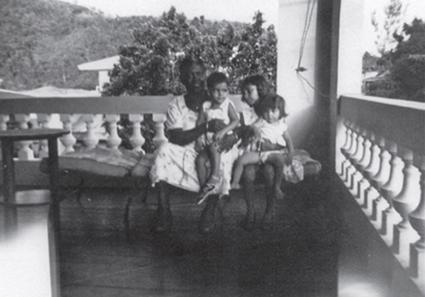

During the funeral, the family's silence that Dean had renounced in his essays was palpable: the mother's "five years in Trinidad" are missing from the publicly read-out résumé - "hushed [...], my beginnings [...], as never happened, clipped away, like cutting out a naughty scene in a movie" (page 63). What is omitted in the biographical fast-forward of the mother's story, however, is preserved in the stillness of the photograph. In the mother's estate, the narrator comes across an album, a private counter-archive, which preserves and bears witness as a "certificate of presence" (18) to what should be erased from social and family memory: "They are pictures from the lost world of my childhood. Black and white prints of my mother and me, [...] of tropical beaches, palm trees, of laughing black people." (page 14)

These photographs, reproduced in the novel, trigger a search for clues that is narratively staged as a treasure hunt - an ironic play on colonial adventure stories, whose models Dean consciously evokes and subverts. However, the images not only lead back to the "sunken continent" (ibid.) of his childhood; they also open up a view of repressed colonial historical contexts.

One photo, for example, shows the narrator as a child among workers on a cocoa plantation (page 17), where his mother worked as a secretary. This scene, which at first appears idyllic, refers to the plantation capitalist economy of Trinidad which, in the course of the narrative, is linked back to its colonial origins and exploitation structures, prompting reflections on the history of slavery and forced labour, which have contributed to European prosperity to this day.

Another shot shows Irene, the black nanny employed to care for the protagonist as an infant (page 20), and initially alludes to the social and racialised hierarchies in Trinidad. In the narrator's memory, such hierarchies resurface later in Switzerland, when he describes his childhood village as "white" (page 38; emphasis added) and understands in retrospect why his own affiliation, which his mother insistently claimed - "You're a Swiss boy, you hear!" (page 25) - remained socially precarious. The photograph thus creates a kind of transregional resonance chamber. It reminds us that the demarcations that were structural in Trinidad continued on a daily basis in Switzerland.

From a poetalogical perspective, this process - the use of photographs as triggers for a narrative reconstruction of repressed history - can be related to Saidiya Hartman's practice of "critical fabulation" (19). In Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments (2019), Hartmann takes photographs of black women from around 1900 as a starting point to reclaim their erased voices in fiction. On the other hand, Dean draws on W. G. Sebald, in whose work reproduced photographs oscillate between autobiographical experience and a "supra-individual" "epochal signature" (20). The fact that Tobacco and Chocolate is preceded by a quote from Austerlitz (cf. 5) indicates that here, too, a personal story of self-searching is intertwined with a larger, historically charged history of violence.

Food and luxury goods

Even before coming to the photographs, the title and cover of the novel evoke two traces of memory: Tobacco and Chocolate. Through their taste and smell, the narrator remembers the "Schoppen[]"(baby bottle) (page 18; emphasis added) of his childhood and the smell of his grandparents' house (cf. page 147) - an effect that corresponds to the special link between olfactory and gustatory stimuli and episodic memory. (21) At the same time, tobacco and chocolate represent goods whose global circulation is embedded in colonial economic and trade relations. In the novel, they link different strands of family history: Caribbean tobacco leads to Aargau, where the grandparents were employed in cigar production at Weber & Söhne and Villiger respectively; Swiss chocolate to Trinidad, to the cocoa plantation where the mother worked.

Tobacco and chocolate thus do not appear as depoliticised consumer goods, but as historically situated products, classic illustrations of colonial links: "Colonialism goes through the mouth and stomach" (page 173). Accordingly, other foods appear in the novel - pineapples, bananas, dates, oranges, lemons (see page 183f.), tea (see page 121), or sugar (see page 118) - whose trade routes span continents and centuries. This creates a cartographic awareness: Each of these goods functions as an indication of global circulations in which familial memory and colonial history intertwine - much like in the photographs.

This intertwining is particularly vivid in the example of the potato (see page 145). The novel traces its migration history from the high Andes via the Spanish colonies to Europe - a history in which the tuber both alleviated hunger and triggered migratory movements in times of crisis. In the narrator's family history, the potato blight in the Emmental around 1850 precipitated the emigration of the Swiss great-grandfather to Rügen. His daughter later returns to Switzerland when living conditions on Rügen deteriorate.

In short, the novel shows how colonial links are evident in everyday goods. This places Dean in a series of texts from recent decades that focus on colonial goods as media of memory - often already in the title - a phenomenon that, to my knowledge, has not yet been systematically investigated. Examples include Alessandro Baricco's Seta (1991), Dany Laferrière's L'odeur du café (1991), Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni's The Mistress of Spices (1996), Andrea Levy's Fruit of the Lemon (1999), Dorothee Elmiger's From the Sugar Factory (2020) and Amitav Ghosh's The Nutmeg's Curse (2021).

Bodies (22)

If colonial history is deposited in food and luxury goods, then it is literally incorporated into the food. However, the novel demonstrates that the same history is also passed on as hunger. In a key scene, the protagonist talks to his Trinidadian relatives about his great-great-grandfather's crossing from India to Trinidad in 1876. Having discussed the precarious conditions on the former slave ships - now a means of transportation for contract workers - the family eats "with the appetite of survivors": "And when we were long full, we kept eating, coconut ice cream, mango ice cream, chocolate ice cream, so that we could be sure we had survived Kaala Pani [the crossing of the sea], once and for all." (page 121; original emphasis)

Eating beyond the point of satiety acts as a physical self-insurance; as if an inherited memory of deficiency is being soothed. Elsewhere, the narrator speculates that the "drama" of his grandmother's "times of hunger" - "who ate boiled shoe soles during the war" - has left its mark on him (page 44). Hunger no longer appears here merely as a physiological condition, but as a transgenerationally transmitted experience that continues as a sensation, attitude and bodily knowledge. This also applies to the experience of being uprooted: according to the narrator, the insecurity of the ancestor during the crossing left a lifelong urge in his "body" to change location(page 114).

In this way, Tobacco and Chocolate picks up on a theory discussed in trauma and epigenetics research: that experiences of one generation can continue physically and psychologically in the descendants - that, as the psychologist Brian Koehler puts it, "the 'nurture' of one generation" can become the "'nature' of the subsequent generations". (23) When the narrator describes his Indian heritage as being "deep in his bones" (page 87), this idea is literally embodied.

Archival traces can also be seen in the phenotype - for example in the external similarities between the narrator and his relatives. When the narrator sees his Aunt April for the first time, he is surprised to see "my face mirrored in the features of the eighty-eight-year-old woman" (page 92). In addition, skin becomes a carrier of historical violence: its "colour" (page 43) is read socially and evokes the history of colonial-racist devaluation. The novel illustrates this, for example, in a scene in which the protagonist, as a child, has the N-word thrown at him by a classmate immediately after throwing a coin into a "Nickn*" figure at Sunday school - a moment that causes "[e]very heat" to rise up in him, "threatening to burn him" (page 24). In this experience, the narrator loses his unmarked sense of belonging, just as Frantz Fanon described in Peau noire, masques blancs: Under the colonial gaze, the "schéma corporel" disintegrates and gives way to a "schéma épidermique racial" - the body is reduced to its skin, a visible racial difference. (24)

The motif of burning, to which the childhood scene refers, points in two directions. On the one hand, it leads back to a scene at the beginning of the novel, in Trinidad, where the drunken father - immediately before the mother flees from him - tries to put out his cigarette on the skin of the toddler, which he does not succeed in doing (cf. page 7). This leaves no scar, no lasting trace; the memory remains physically unsecured. On the other hand, the burning motif refers to the life story of the writer Edgar Mittelholzer - a Guyanese with Swiss roots - who, after years of racially induced self-degradation - with Fanon one could say: after completed "épidermisation" (25) - pours petrol over himself and sets himself alight.

The narrator knows the episode with the cigarette from his mother's memory; it is one of the few fragments she tells him about his father. In turn, a bookseller introduces him to Mittelholzer's literature and biography - Mittelholzer had ancestors from Appenzell (see pages 130-132). His story - and the way in which it has been passed down - opens up the idea that memory appears in the novel as a network of transmissions. It circulates between oral tradition, literary-artistic composition, historiographical knowledge and material carriers. In this way, historiography, oral history and literature, together with the material and affective traces that the novel evokes - bodies, photographs, colonial goods and - as could be shown with a little more space - films, music, names, furniture or feelings of shame - form a polyphonic archive that is only linked into a dense web in the act of storytelling. By exhibiting and thematising this process, Dean's novel also refers back to Borges' Funes, el memorioso, where remembering itself becomes the motif and actual reason for the storytelling.

+++

Did you enjoy this text? If so, please support our work by making a one-off donation via PayPal, or by taking out a monthly or annual subscription.

Want to make sure you never miss an article from Literatur.Review again? Sign up for our newsletter here.

(1) Jorge Luis Borges, ‘Funes, el memorioso,’ in: ibid., Ficciones, Madrid, Alianza, 1974, pp. 123–136, here p. 131: ‘He knew exactly what the southern clouds looked like at sunrise on 30 April 1882 and could compare them in his memory with the grain on a parchment strip that he had only seen once.’ Jorge Luis Borges, ‘Das unerbittliche Gedächtnis’ [The Relentless Memory], in: ibid., Fiktionen. Erzählungen 1939-1944 [Fictions. Stories 1939-1944], trans. by Karl August Horst, Wolfgang Luchting and Gisbert Haefs, Frankfurt am Main, Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 1992, pp. 95-104, here p. 100.

(2) Cf. Martin R. Dean, Die verborgenen Gärten, Munich and Vienna, Hanser, 1982, p. 85.

(3) Borges, Das unerbittliche Gedächtnis, p. 95: “aindiada”. Ibid., Funes, el memorioso, p. 123.

(4) Borges, Das unerbittliche Gedächtnis, p. 95: ‘Zarathustra’. Ibid., Funes, el memorioso, p. 124.

(5) Borges, Das unerbittliche Gedächtnis, p. 103: ‘más antiguo que Egipto’. Ibid., Funes, el memorioso, p. 135.

(6) Borges, Das unerbittliche Gedächtnis, p. 103: “monumental como el bronce”. Ibid., Funes, el memorioso, p. 135. See Madilyn Abbe, ‘“Hopelessly Crippled”. The Construction of Disability in Borges' Funes, His Memory,’ Criterion. A Journal of Literary Criticism, vol. 16, no. 1, 2023, pp. 13-27, here pp. 21-23.

(7) Borges, Das unerbittliche Gedächtnis, p. 99: ‘No trataré de reproducir sus palabras.’ Ibid., Funes, el memorioso, p. 129.

(8) Borges, Funes, el memorioso, p. 129: ‘I prefer to summarise truthfully the many things Ireneo told me.’ Ibid., The Relentless Memory, p. 99.

(9) Borges, Das unerbittliche Gedächtnis, p. 179: ‘Literato, [...] porteño.’ Ibid., Funes, el memorioso, p. 123.

(10) Dean, Die verborgenen Gärten, p. 85.

(11) Cf. Walter D. Mignolo, Local Histories / Global Designs. Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges, and Border Thinking, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2000, pp. 91-214.

(12) Martin R. Dean, In den Echokammern des Fremden, Zurich, Atlantis, 2025, p. 75

(13) Ibid., p. 86.

(14) Cf. Stuart Hall, ‘The Question of Multiculturalism,’ in: idem, Ideology, Identity, Representation, ed. by Juha Koivisto and Andreas Merkens, Hamburg, Argument, 2004, pp. 188-227; Stuart Hall, ‘The Multicultural Question [2000],’ in: idem, Essential Essays. Vol. 2: Identity and Diaspora, ed. by David Morley, Durham, Duke University Press, 2019, pp. 95-133.

(15) Patricia Purtschert and Harald Fischer-Tiné, "Introduction. The End of Innocence. Debating Colonialism in Switzerland," in: ibid. (ed.), Colonial Switzerland. Rethinking Colonialism from the Margins, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 2015, pp. 1-26, here p. 4.

(16) Georg Kreis, Blicke auf die koloniale Schweiz. Ein Forschungsbericht, Zurich, Chronos, 2023. From 13 September 2024 to 19 January 2025, the Swiss National Museum also hosted the exhibition kolonial – Globale Verflechtungen der Schweiz (colonial – Global Interconnections of Switzerland). See Swiss National Museum (ed.), kolonial. Globale Verflechtungen der Schweiz, Zurich, 2024 (last accessed: 25 November 2025).

(17) Martin R. Dean, Tabak und Schokolade, Zurich, Atlantis, 2024, p. 9. Subsequent references in the text are indicated in brackets.

(18) See Roland Barthes, La chambre claire. Note sur la photographie, Paris, Gallimard, 1980, p. 135. The reference to Barthes is also obvious because Barthes begins his reflections in the second part of the note – like Dean in his novel – with the death of the mother; kindly pointed out by Cornelia Pierstorff, Zurich.

(19) Saidya Hartman, ‘Venus in Two Acts,’ Small Axe Vol. 12, No. 2, 2008, pp. 1-14, here p. 11.

(20) Silke Horstkotte, ‘Photographie / Photographieren,’ in: Claudia Öhlschläger and Michael Niehaus (eds.), W. G. Sebald-Handbuch. Leben – Werk – Wirkung, Stuttgart, Metzler, 2017, pp. 166-174, here p. 167.

(21) Cf. Rachel Sarah Herz, ‘The Role of Odour-Evoked Memory in Psychological and Physiological Health,’ Brain Sciences Vol. 6, No. 3, 2016 (last accessed: 25 November 2025).

(22) I would like to thank Alexander Bratschi, Bern, for important information on this chapter.

(23) Quoted from Jil Salberg and Sue Grand, Transgenerational Trauma. A Contemporary Introduction, Abingdon, Routledge, 2024, p. 34.

(24) Frantz Fanon, Peau noire, masques blancs, Paris, Éditions du seuil, 1952, p. 90.

(25) Ibid., p. 8.