Roots

It is summer in the global North and winter in the global South. Reason enough to bring summer and winter together in August's Literatur.Review and publish previously untranslated or unpublished stories from the North and South of our world.

María Ignacia Schulz Afro-Colombian-German researcher, writer and translator. PhD candidate in Humanities and Digital Society at the International University of La Rioja and member of the GREMEL Research Group at the same university. She holds a Master's degree in Spanish and Latin American Literature (International University of La Rioja) and studied Linguistics and Literature at the University of Cartagena (Colombia), where she also taught Colombian literature, among other subjects. She is a Research Associate of the ERC Starting Grant Project AFROEUROPECYBERSPACE (University of Bremen) and a member of the Research Group De Áfricas y Diásporas: Imaginarios Literarios y Culturales at the University of Alcalá. Her research interests include identity constructions, Hispanic Afro-Caribbean literatures, Black and Afro-Caribbean feminisms and Afro-Cyberactivisms in the Spanish-speaking world.

And once you got to the top, you could see it all and you would feel such happiness

that it would be enough to make you never worry again for the rest of your life. - Amy Tan

Old Stahl has gone back to work in his garden. Days ago it dawned on me that it was empty, barren, the soil grey as cement. Usually by this time of year, it would be full of promise, plants already standing upright and shiny, but there were none to be seen. From my window I observe that he has a hoe in his hands, his movements quite slow. He moves forward, one foot after the other. He is almost ninety years old yet there is so much confidence in what he is doing. The wisdom of someone who all his life has done nothing but sow. His garden, a plot of about 800 m2, had something to offer all year round: at the end of spring, lettuces would be in full bloom, their green leaves populating the garden. With the summer sun, the first sunflowers and the plants that would announce red, juicy, delicate tomatoes could be seen. Once, after my dog crossed into his yard and I desperately tried to apologise, he waved me to wait a moment and returned with a butternut squash and a bunch of beets.

Our garden is also large and Sebastian has taken to planting vegetables, greens and lately flowers for me. He's discovered in himself a farmer's vocation, like all our neighbours on this side of the street. Our house, like the others, was once a farm where people raised animals and grew whatever they needed to keep from starving. Unlike us, though, our neighbours were born here. One generation welcomes the next - living with old Stahl and his wife were his son, daughter-in-law and the grandchildren and no doubt the great-grandchildren would eventually live their too, long after the great-grandparents are gone.

The Stahl family used to sell their harvest in the market places and in some local supermarkets, but with the brutal competition generated by the big distributors they could no longer sell their products, so they decided to continue planting only for family consumption. This is what he told me when we chatted over the fence. Or at least that's what I thought I understood, because he speaks Franconian dialect and many times I nod my head pretending to understand, simply to continue the conversation and listen to his tumbling waterfall of a voice. He told me that the situation had become difficult and his son had decided not to farm anymore, not to continue the family tradition. He, on the other hand, kept getting up between four and five in the morning to start the day's work: activate the irrigation system, remove the weeds that dared to get between his beloved plants, hoe if necessary and pick the fruits that he knew were ready to eat. He must have a large family that spreads beyond the confines of the neighbourhood as here, they are only six and they surely can't consume as much lettuce as that garden produces: as he speaks I think of lettuce salad, marinated lettuce, garlic lettuce, lettuce for the sandwich, lettuce... lettuce. How can they eat so much lettuce? He never gave me one, although I would have liked to try them. They looked big, round, green and fresh.

I say goodbye to old Stahl and return with my dog to my garden. I stop in the middle and slowly turn full circle. This is my garden. This is my home. Here I will die, I tell myself, and a certain trembling moves from my feet to my ears. I close my eyes and think of my mother in Cartagena. Surely she too once stood in the middle of our garden, saying these same words and trembling like this.

***

I had already been to Germany some twenty years before, on holiday. On that occasion the world seemed newly invented to me. A wide meadow of fresh, bright green opened before my eyes. The train was flying, but I didn't care about its speed, only about the wide green and yellow rapeseed fields that from time to time we crossed. My eyes were widening as if wanting to catch it all, the colour, the brightness, the summer. I can imagine that a smile came to my face. It could not be otherwise. I was happy to have dared to cross the 'puddle', as we called among my friends Mr. Atlantic Ocean, in an attempt to conceal the fear of that adventure that had begun a couple of weeks ago when I met Erich.

We had met only three times: the first time, it was an afternoon - I was dressed in blue with my hair down and had a pile of exams to review. He asked what my name was, what I was doing, why the film hadn't started yet, if I would agree to go out dancing with him. I answered that my name was Camila, that I was teaching, that the film would start on time because they were very serious at the institute, that he should calm down and that yes, we could go dancing. But I didn't go. That could have been the second time, instead it was in a salsa bar. I was looking across the balcony towards the Clock Tower to check the time and I was about to take a few steps alone, when I saw him come in. There he was, the guy from a couple of days ago who had probably been waiting for me. I tried to hide between the beer and the rhythm of a song I can't remember now, but I couldn't stop him from approaching me. And again an appointment scheduled, now for Sunday. I arrived two hours later than agreed, with Isabel, my friend who had convinced me to get up. At least this time you arrived, was his greeting. And eight weeks later I was with him on a train from Frankfurt to Stuttgart, looking out of the window as if the world and I had been created at that very moment. I felt the happiness of a little girl who has got up to the most wonderful mischief without having soiled her white school tennis shoes.

It was the first time I had left Cartagena. Actually, the second. The first time I went with my friends to Punta Arena, an island located about fifteen minutes by boat from Cartagena. On that occasion, unused to packing for a trip, I had forgotten many things, including a toothbrush. Since then, I always keep one in my bag, even if I go grocery shopping. But this was my first time traveling by plane. If I think about how I have sworn never to get on one again, unless absolutely necessary, because of the anguish and fear it causes me - the uncontrollable trembling that starts in my throat, the sweating hands and my compulsion to grip the seat - I can't imagine how I can have been happy that first time.

Erich took me to his perfectly tidy little two-room apartment: everything in its place and too much of everything for my taste and peace of mind. Batteries in unfamiliar voltages, paper towels piled up on a shelf, stacks of canned milk, light bulbs, nails and screws of all shapes and sizes. Soaps, dishwashing sponges, oil, salt...more of everything in the apartment could be found in that little chamber that I had accidentally discovered my first morning in Germany. I was alone and I still remember the horror that came over me. Could I be in the hands of a psychopath? How can you have so much of everything, ordered by size to the millimetre, by colour, by use? In my house there was only what was there for the day. If you needed a new light bulb, you went to the shop. If you ran out of milk, you went to the shop. If you needed a screw, you went to your mechanic neighbour. Tools were borrowed from any house and stayed until another neighbour might need them. I reassured myself that I had organised that trip with all the documentation in order, his and mine. If something happened to me, at least at some point they would find out who had butchered my body and where it had been hidden. The most important thing was that they would find me, dead or alive. So that first morning after my deadly discovery, I decided to stand outside the window waiting for Erich to return from work. I wonder why I didn't run away. It was a sort of mystical fascination for that new world that made me wait for my death there, in front of the window, looking at that sky less blue than my Cartagena sky.

Absolutely nothing happened, otherwise I wouldn't be writing this story. It was one of the happiest summers of my life. The peaceful walks through the wine fields, the walks to the beer gardens. Getting on the bus and feeling his hand on my thigh when I wanted to stop the impulse to get up and shout stop! that I already felt coming from my body, and both of us bursting out laughing, attracting the stares of the other passengers. Getting off and crossing the street when the traffic lights indicated, not when I chose to: running, looking from left to right and again his hand restraining my impulses, again the laughter.

***

I went back a couple more times to Germany and he to Colombia. And at some point I thought that here he could die or put down roots - another way to talk about wanting to die in a certain place. Until that night when we were leaving a nightclub in Dresden. We had to take the subway to the final station and there take the cab he had already ordered. A couple of hours more and we would be back at his parents' house, where we were staying on that occasion, in a small town called Pirna. It was after two o'clock in the morning. In the subway carriage were a couple of other passengers. All with their black coats, their black hats, their black gloves. It was winter and very cold. Suddenly I felt as if something heavy was being placed on my right shoulder and I turned my head towards the window. Three young men with shaved heads and wide jackets were looking at me intensely and at the same time gesticulating non-stop. They got on the train, walked past me and said "Scheißneger". They sat diagonally across from us in such a way that they could continue to harass me. Scheißneger, I learned later and never forgot, means "fucking nigger." Black, in my case, I think. Fucking nigger. The other passengers began to get restless. Erich looked at me and told me not to pay attention to them, that they just wanted to provoke, tease a little and nothing more. I imagine that the other people in the carriage thought the same thing, because little by little they left us alone with them. Maybe they didn't have to go to the end of the line as we did, even less now that the atmosphere was getting heavy, dense. A voice announced the final station and with it, the instruction that all passengers must leave the train. The three young men did so first, then Erich and I. As we walked, we saw them a couple of metres ahead, holding sticks. They seemed to be waiting for us, and when they saw us, headed in our direction. Erich, as he always did when he wanted to point something out to me, grabbed my hand, but this time he held it so tightly that it hurt. He started to run, pulling me back towards the train. We got on in a hurry and under the driver's bewildered gaze, a conversation began which, as I found out later, was about us having to leave, that it was the final station, that no, that some young men were waiting for us outside with sticks in their hands, to call the police please, that they were called but they said nothing was going on, and then Erich remembering that he had ordered a cab which should already be waiting for us further on. One more call and the cab pulled up, right to the train driver's cab door and that's where we exited the train. Eric's knees shook, he later confessed to me. When the cab driver heard what had happened, he commented in impeccable Spanish that he was married to a Mexican woman and that they had been living in Dresden for fifteen years and nothing similar had ever happened to them. The idea of the tree taking root was already incubating in me when I silently decided that I would never live in Germany. Then I remembered that I had already felt strangely lonely in Pirna. In the street there was no one else like me, I mean, black. Being different had most of the time been a source of pride, to walk upright and confident. Here, only when I looked in the mirror did I discover another woman like me. We decided to return immediately to Stuttgart, supported by Erich's friends who were just now asking him how he could have thought of travelling by public transport with a black woman in eastern Germany. And I thought, when he told me about it, almost apologising and wishing that my roots would stay with him anyway, that how could he not foresee it and I forgot about the tree, the roots and their leaves and all that bullshit. I vowed not to go back. Once fear sets in, you don't know how to dislodge it. My skin bristled and trembled every time I saw shaved men. Many would smile back at me with their eyes, not understanding why I was suddenly immobilised as I passed them on the street. Sorry, they would say, thinking they had blocked my path. I was just shaking. And, later, in the apartment, I would cry my eyes out, unable to stop, furious because it made no sense.

***

And so the days passed, as some song says. Also the story with Erich happened. It happened one night when I was accompanying Esteban to see a film by a German film director: The Devil's Accordion. Esteban placed his right hand on my left hand, without saying anything and left it there. I was startled, but I kept silent, I didn't want to read more into a simple gesture like that. We walked silently back to the institute and said goodbye. My head was spinning and I was already wondering if I should look for the fly in the ointment, whether I should look again at those eyes that many months ago, had captivated me, even before I had met Erich.

***

Old Stahl had been taken to the hospital. I saw the ambulance approaching and noting the abandonment of his garden I assumed it was him they were looking for. From my living room window overlooking the street, I can't confirm if he is the one they have taken. A certain sadness inevitably settles in my eyes and I look inward. I go over the memories: my father's raised hand in a gesture of farewell, my mother's soft kiss resting on the fingers of his hand, the snow falling and my boots without the proper soles threatening to make me slip, Esteban's parents brimming with joy. The images crowd in and I run out into the garden. It is already more than sixteen years in these lands. I still don't speak the language of Anna Seghers or Julia Frank, no. I don't speak the language of Anna Seghers or Julia Frank. My tongue is a pierced tongue that on crystal-clear days flows without hesitation and on others, seems as though the language is newly learned. My tongue also speaks in accents that know of its multiple roots and lets out stunning laughter and unheard music. My children, on the other hand, cross the waters of languages without fear and sometimes invent words that tell of their worlds; they flow and I know that they know they are true and pertinent here. As I think about it I see myself stopped, planted in the middle of the garden. I stretch out my arms like wings and try to make gentle turns that will lift me up, but from my feet vigorous roots emerge, fast and deep, descending deep into the ground. Some kind of terror seizes me and I cannot return to the house. I am the apple tree and the nut tree at the same time, and tiny leaves emerge from my ears.

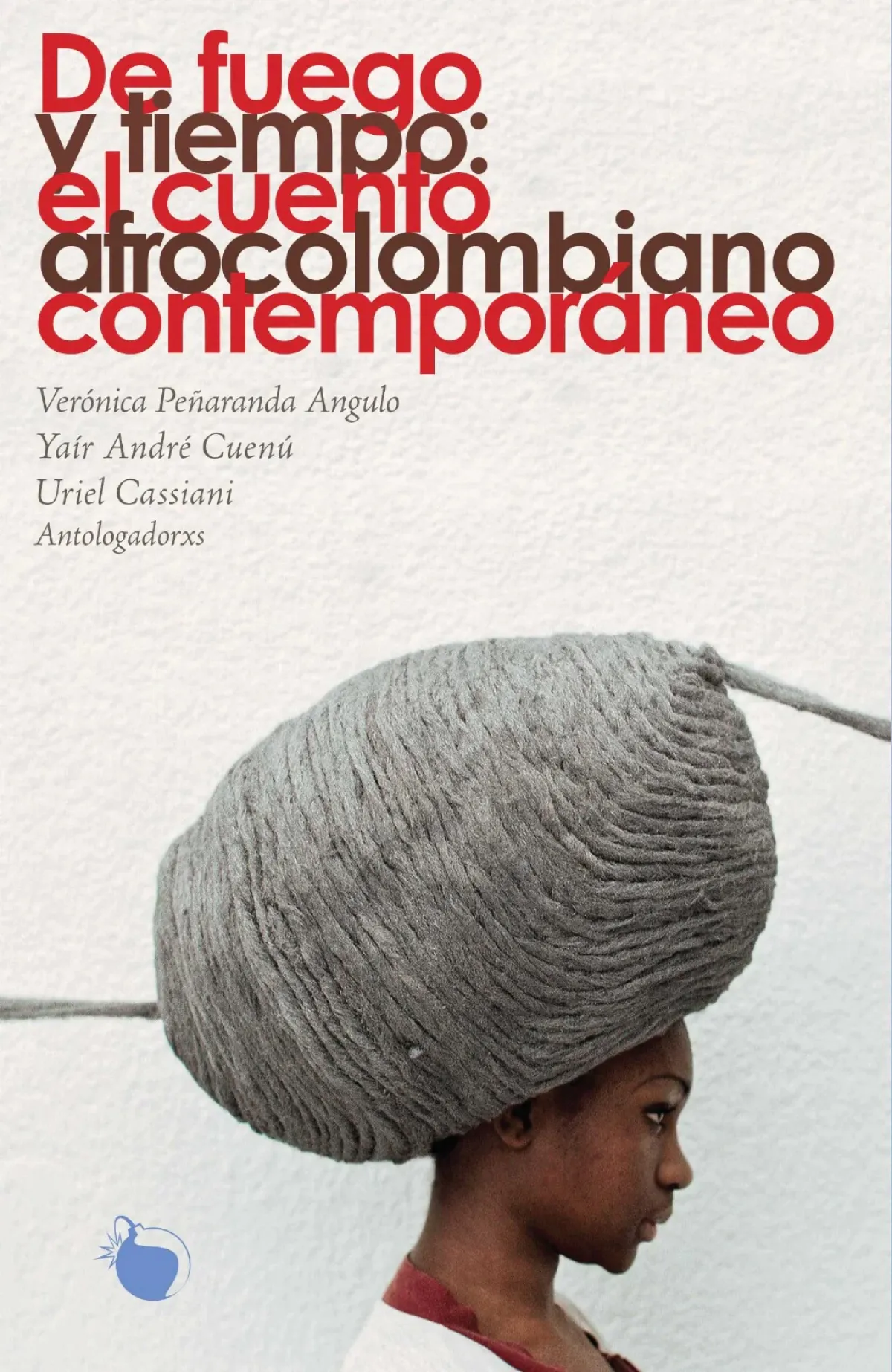

De fuego y tiempo: el cuento afrocolombiano contemporáneo | Verónica Peñaranda, Yaír André Cuenú, Uriel Cassiani | El Cuarto plegable | 224 pages | 65,000 COP | Cover image Pelucas Porteadores: Liliana Angulo Cortés

About the story

Published in: De fuego y tiempo: el cuento afrocolombiano contemporáneo (Lugar Común Editorial, 2023). Anthologists: Verónica Peñaranda Angulo, Uriel Cassiani and Yaír André Cuenú M.

+++

This anthology is composed of 24 stories written by eight authors and twelve authors and the cover image -assimilated as part of the compilation-, the work of visual artist Liliana Angulo Cortés. Its two-part structure, "Of Fire" and "Of Time", alludes to the very image of the invention of fictional time that was told under the fires of the caves, in ancient times when the ancestors of all mankind told stories. The whole compilation is impregnated with age, thematic, linguistic, stylistic and professional variety. The decision to classify was based more on the timing of publication than on other variables. As far as internal organization is concerned, an author and an authoress are interspersed, as far as possible, in succession. In "De fuego", we opted for a conventional form of organization starting with one of the pioneers, in "De tiempo", we made use of chance as an organizing principle.

The name of the first part is a tribute to the figure of fire -which we have been explaining- as a motive for the first narratives. It is adorned with eight stories, five published and three unpublished, belonging to inspiring and/or canonical persons of this genre: Carlos Arturo Truque, Sonia Nadhezda Truque, Alfredo Vanín, Amalia Lú Posso, Pedro Walther Ararat (posthumous tribute) and Adelaida Fernández Ochoa. In the second part, "Of Time", we find a range of unpublished stories written from different parts of the country and the globe. Like the perceptions of time, these stories are presented with a motley of possible worlds for which they are responsible: Estercilia Simanca Pushaina, Uriel Cassiani, Giussepe Ramírez, Rubén D. Álvarez Pacheco, Trilce Ortiz, Juan Sebastián Mina, Hernán Grey Zapateiro, María Ignacia Schulz, Yaír André Cuenú Mosquera, Luis Mallarino, Isabella Sánchez Victoria, Sedney Suárez Gordon, Robinson de Jesús Quintero and Ana Yuli Mosquera.

The stories presented here link us, from the outset, with nostalgia, the proximity to death, the admiration of love, the reinstallation of life, oral tradition, music as a motor of spaces and identities, the opacity of the human condition, the celebration of the hidden.

(This text was taken from the introduction of the book.)