The mother of the house

It's summer in the southern hemisphere and winter in the northern, and in February Literature.Review brings them together and publishes previously untranslated or unpublished stories from the north and south of our globe.

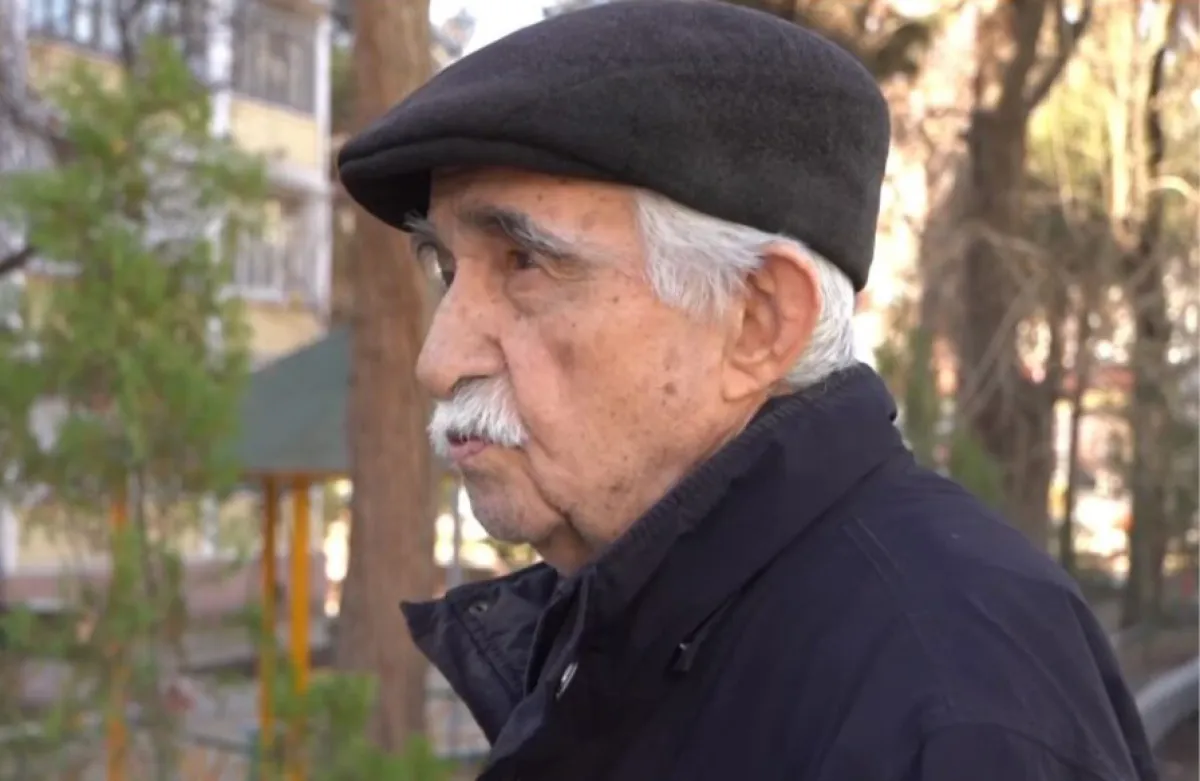

Urun Kuhzod (Urunboj Dschumajew) is one of the most important contemporary prose writers in Tajikistan. The popular writer and winner of the Rudaki and Aini Prizes was born in Punjakent in 1937 and began his literary career with the satirical magazine Chorpushtak. His precise powers of observation and social criticism were evident there early on.

Kuhzod's work combines psychologically finely drawn characters with sharp social criticism. Questions of national self-image, moral conflicts and the historical experience of the Tajik people are central. As a translator of Anton Chekhov and Gabriel García Márquez, he also made an important contribution to the mediation of world literature. His work is considered the pinnacle of modern Tajik prose.

His best-known works include Sarewu sawdoje (1971), Rohi aghba (1971), Kini Chumor (1976), A long, very long day (1977), the novel The Free Prisoner (1994), which won the Rudaki Prize, and the later works Hajdscho (2014) and Sharper than the Sword (2019).

In this house, she and the radio wake up before everyone else every morning. Every night, she and the radio go to sleep after everyone else. Today, she got up before everyone else again. She woke up and quietly, so as not to disturb the children's sleep, put on the Chapan (1) over the same dress she had slept in. All five of her children - boys and girls aged five to sixteen - and she sleep in one room on the floor. Their beds stretch in a row from one end of the room to the other, hers nearest the door.

Carefully, she straightened the blanket that had slipped off the smallest one and slipped silently out into the yard. As soon as she was outside, the radio hanging on a nail in the wall broke into the chatter that, from that minute on - six in the morning - until late at night, would be incessant. The mother is equally non-stop with the housework. You know exactly when and what the radio will be talking about and when and what your mother will be doing.

On the veranda, she washed with cold water and noticed that the days had shortened. She went to the barn with a bucket, threw a bunch of hay into the rack, knelt down and began milking the cow. The cow gave half a bucket of milk, which she brought into the house. Taking two more buckets, she went to the irrigation ditch to fetch water. The water in the ditch had dwindled; soon the canal would be blocked and it would dry up completely. There was no water anywhere else in the village. And then, until spring, when water would be needed again to irrigate the gardens and fields, people would have to use imported water. It would be brought in by car from the river and every drop would count. Disputes would flare up over every bucket of water - a bucket fight. When she remembered the years without water and imagined the days that lay ahead, her heart grew heavy. She thought anxiously of the worries and fears about the water to come: whether there would be enough or not. She dipped the buckets halfway into the ditch in turn, swinging them back and forth to remove mud and dirt from the surface, thus scooping up "clean water". By the time she got home, the spilling water had soaked the hem of her clothes.

She flipped up the hems of her chapan, tied her belt and, after opening the oven door, swept out the ashes. She broke damp twigs, placed them inside, shoved dry wood chips underneath and lit them with a match. The wood shavings flared up with a bang and the twigs began to smoke. The smoke hit her in the face and made her eyes burn. Tears hung like diamonds from her eyelashes. This was the only "jewellery" she had. Silently, she closed the oven door.

She woke the children so they wouldn't be late for school. The fire in the stove blazed up and the chimney hummed with smoke. She put two dung cakes in the stove to help the fire burn longer and keep the heat in. She put a kettle full of water and a bucket of milk on the stove. The children dragged themselves out of bed, rubbed their eyes and went out onto the veranda. After hastily washing themselves like kittens with water from the jug, they came in and sat down at the dastarchan (2). A concert started on the radio.

(1) Chapan - traditional, often quilted kaftan or cloak from Central Asia

"Eat, eat faster," she urged, placing a bowl of milk on the dastarchan. "It's already time for school." The children barely moved; their slowness irritated her. She broke the flatbread herself and crumbled it into the bowl. "Eat up and off to school!" she ordered and went out, taking a broom from the corridor.

(2) Dastarchan - cloth or surface on which food is presented

She swept the porch first, then the courtyard. The yard was large and unkempt. Gates and doors were crooked, the plaster had fallen off. In one corner was a pile of rubbish and dung, in another a pen for goats and sheep; here a mountain of cotton stalks - the most important and constant fuel in the village - and on the roof of the cowshed a pile of hay. This unappealing sight improved after she had swept the yard clean; the peeling walls and crooked gates were no longer so noticeable.

As she swept outside the gate, the children went to school one by one - some with a schoolbag in their hands, others with their satchels on their backs. Pupils from three villages came to her children's school, so it was a long walk. This long walk also saddened her, but what could she do? Having finished sweeping, she straightened up without putting down the broom and threw her thin braids over her back.

"Your whole kettle is boiled, mother!" said the husband, propping up the cracked wall with the fork of an almost dry willow branch to prevent it from collapsing. She made tea and spread out the dastarchan for him. She sat down and ate a piece of flatbread, which she dipped into the teacup.

"I'm off to work in the fields," said the man, getting up and tying a belt cloth over his chapan.

The mother went into the bedroom. The little son was sleeping so sweetly; she was sorry to wake him up. She tidied up the four other beds, folded the mattresses and blankets and placed them neatly in the alcove. The radio reported the latest news. It was time to put the cattle out to pasture. She led two goats, two sheep, a ram and a cow out of the pen and the barn and drove them from the farm.

In her youth, there had been a goatherd, a shepherd and a cowherd in the village; large and small livestock were not grazed together. Each type of livestock had its own pasture, its own shepherd, there was order and fixed rules. Now there were few cattle and no shepherds. Cows and sheep grazed together. Today this family was herding, tomorrow another - whoever had time was the shepherd. That's why there was no fat in the sheep's tails, the goats' ribs were protruding and there was hardly any milk in the cow's udder. It seemed as if everything was lacking. As if everything was done under duress. As if people were only living here temporarily. Next Tuesday it was their turn to herd the cattle. If it had been the weekend, the children would have gone. Once they went herding, the whole household fell behind for a day, as if no one had looked after them for a month. And what a life it was - not a single day of rest.

As soon as she was back in the yard, she heard crying. Her little son was sitting barefoot on the porch, sobbing and wiping the tears from his face with his hands.

"My darling, what's happened? Why are you crying?" she asked, picking him up dirtily from the floor and hugging him.

"I wet the bed," he continued to cry.

"So what? Is it worth crying over? Don't cry, my darling, it's all right, I'm here!"

The boy calmed down in her warm embrace. She changed him, sat him by the stove and wiped away his tears.

"Now I'll give you some milk."

Mother and son ate, crumbling flatbread into a bowl of milk. Then she carried the blanket into the yard, rinsed out the wet spot and hung it on the line. She collected the dirty laundry on the porch; a whole pile had accumulated. She brought two buckets of water, poured them into a basin and went to fetch water again. She split wood, lit the stove fire and put water on to heat up.

She put almost half of the dirty laundry in the basin, soaked it and sprinkled washing powder over it. The radio on the porch was still playing. Someone was ranting in a loud, unpleasant voice about the culture in the country. He said that the level of culture was far from meeting the demands of the times. People were careless with the culture of their everyday lives; the farms were neglected, things were lying around everywhere. The low culture is particularly evident when it comes to dealing with children: Parents shied away from buying their children tables and chairs for homework.

"And what's he talking so much about?" she shrugged discontentedly as she squatted and kneaded the laundry. "He talks and talks. He probably has no worries. How many children does he have himself, that would be interesting. And how much does he earn?"

In the village, the children sleep almost on top of each other, and he talks about tables and chairs.

She did the laundry. The water in the basin turned blue, then black. She poured it out, filled it with new water, put more laundry in and sprinkled powder over it again. She washed everything in three cycles. She spread the laundry out on the mat, rinsed the basin, put the clothes back in, lifted it upside down and went to the ditch. There she rinsed everything out, her hands red. With the basin on her head, she returned, stretched out a line and hung up the washing.

"Mummy, I want to eat," said the little son.

"I'm hungry too, my darling."

She spread a rug on the veranda and covered the dastarchan. They drank sweet tea and ate flatbread, which they dipped in the tea. These minutes were brief respites. Then she had to fetch water again, prepare something warm; soon the children would be back from school. As soon as they arrived, she would have to tell them to clean the stable and look after her little brother while she herself went to the big river to fetch wood. There were cotton stalks for the fire, but they burned quickly. If you threw in a log, however, the fire burned longer.

The children came back from school one after the other. They hurriedly grabbed a piece of flatbread each, threw old aprons over their shoulders and said they were going to collect cotton. The mother knew that such conditions prevailed everywhere and that children worked in the fields after school. If they didn't go, they would be criticised and shamed at the class meeting, at the Komsomol meeting and in the newspaper. But firewood was needed in the household; without wood, there would be no heat in the house.

"Don't go for cotton today," she said to her sixth-grade daughter. "Let her go, but you stay here, take care of your little brother, I'm going to get some wood."

"The teacher will scold me," said the girl hesitantly.

"No, she won't scold you. I'll explain it to her."

She left her daughter and son at home and made her way to the river. She crossed the neighbouring village and the fields there and reached the cotton field. There she gathered brushwood and selected the thicker branches to gain more heat. From bush to bush, from hollow to hollow, over sand and stones, she collected dry branches and broke as many twigs as she could. Finally, she put everything together, tied it and loaded the bundle onto her back.

The fallen wood and thorns scratched her hands. Her lower back and knees ached from the constant bending and straightening, her back was numb. On the way back, she began to sweat, her muscles relaxed and the pain eased a little. With the bundle of brushwood on her back and a branch fork instead of a stick in her hand, she walked over the uneven path - sometimes smooth, sometimes full of potholes, over sand and stones, along the edge of the ditch or across the plain. Sometimes she stooped, sometimes she straightened up to lighten the load. She walked and walked until she reached the asphalt road.

There were only a few cars on the road. Each one that appeared sped past at such speed that she couldn't tell who was in them. They didn't notice her - everyone was preoccupied with themselves, with their own problems.

As she approached the village, the kolkhoz chairman's car stopped beside her.

"What's up, auntie?" he asked, opening the door but not getting out. "Isn't there a donkey to help you carry the wood?"

"Transporting wood with a donkey is a man's job," she replied.

"Then let your husband fetch the wood."

"If he fetches wood and you stroll from party to party, who works in the kolkhoz?"

The chairman laughed. "I'll give you the chairmanship next year." The car drove on. She went on her way.

At home, leaning back against the wall, she drank a pot of tea. The sweat dried, the thirst subsided and she felt a little lighter. She took three roubles out of her pocket and sent her daughter to the store to buy sugar cubes or granulated sugar, if available.

She herself poured flour into a bowl and kneaded dough. She wrapped the bowl in a mattress so that the dough would rise faster in the warmth and she could bake flatbread before nightfall. She lit the fire, put a kettle on and poured water into it. She took meat out of the pot, cut it up, chopped the bones and put one piece per person into the cauldron.

(3) Tandur - traditional, cylindrical clay oven fired from below with wood or charcoal

She brought cotton stalks, sat on the veranda and peeled onions, potatoes and carrots. She threw the peelings into an old bucket and took them to the barn - she would give them to the cow in the evening. She cut the onions into small pieces and threw them into the pot. Then she swept the ashes out of the tandur (3), swept all around and lifted the mattress under which the dough was standing.

(4) Sufra - cloth for portioning the dough

The dough had barely risen. If she waited any longer, she wouldn't manage to get it all done in time. She spread out the sufra (4), formed balls from the dough and flattened them one by one into flat cakes. Her hands, from her shoulders to her fingertips, were in constant motion - so that her children's mouths could also be in motion that evening and the next morning.

She fired up the tandoor. Flames and acrid smoke billowed out, scorching her eyebrows and eyelashes. A foreman spoke on the radio and explained that life in the countryside was hardly any different from life in the city. Laundries had been opened, gas pipes laid.

"Well, the expert is amazed and the layman is surprised," she said quietly and continued with her work.

She baked the flatbreads, one after the other, sprinkling each one with water. In the end, a whole basket filled the veranda.

In the evening, everyone returned. The children from the field, the father from work. They ate soup together with fresh flatbreads. The daughters washed the dishes and took the washing off the line. The animals separated from the herd as if by magic. The mother milked the cow and put the milk in a cool place.

Later, she mended clothes. A seam had come undone on one dress and a button was missing on another. As she was sewing the collar of an old jacket, she was suddenly overcome by a knot of resentment, bitterness and pain. Her eldest son had worn this jacket when he joined the army. She hadn't seen him for fourteen months. One was in the north, freezing. Another was in the south, burning with heat. Tears blurred her vision.

She washed her face, put her work aside. The children had fallen asleep, books and exercise books scattered about. She woke them, put them to bed one by one.

The man said through the door, "Wake me up tomorrow along with the radio. I have to leave before dawn."

The house was asleep. Only she was not asleep. She continued mending while the radio broadcast a concert. And when the radio wished the listeners goodnight, she lay down under the covers without changing her clothes and fell asleep - unaware that she was listed as unemployed in the official lists.

+++

Did you enjoy this text? If so, please support our work by making a one-off donation via PayPal, or by taking out a monthly or annual subscription.

Want to make sure you never miss an article from Literatur.Review again? Sign up for our newsletter here.

English adaptation based on the German translation from Tajik by Fazliddin Odinaev.

Translator's note: The text was written in the late 1980s, shortly before the collapse of the Soviet Union. Since then, however, the role of women has gradually improved, and the conditions described here can only be found in rural areas in particular.

The Tajik original can be downloaded here: