Foreigners

It's summer in the southern hemisphere and winter in the northern, and for the month of February, Literature.Review is bringing them together, publishing previously untranslated or unpublished stories from the north and south of our globe.

Al Joseph Lumen is a Filipino essayist now living in Germany. His writings have appeared in numerous anthologies, including in ANI of the Cultural Center of the Philippines and in the magazine Liwayway. For his essay Foreigners: Mga Danas sa Alemanya, he won 2nd place at the Carlos Palanca Memorial Awards 2023 and received the Best Book Non-Fiction prize at the Migration Advocacy and Media Awards 2025.

Just pretend you know how.

My first day as a care worker in Germany - and my palms were sweating. No experience in caring for the elderly, only recently started learning German - who wouldn't be nervous? Arlene said to me: "Take courage, Babe. You can do it. If you don't know something, just ask."

Easier said than done. This job was a huge challenge for me, especially having to say everything in German. How was I supposed to ask a German colleague if I don't even know how to phrase the question in German? So I just kept nodding. Yes, that's how it was.

As soon as I arrived at the home, I immediately looked for the coffee machine. I had heard from the other carers that they always drank coffee in the morning during the handover meeting. That's when the night shift colleagues reported on how the night had gone. My pace slowed as I approached the meeting room. I heard their voices - and panicked. When I entered the room, I smiled broadly and said: "Good morning!" Everyone stared at me. No matter what, I didn't want them to see how nervous I was. Shortly afterwards, the handover began. And I seriously wondered: Is this the right place for me? Can I even do this? Racking my brains, I tried to at least grasp the gist of what was being said, but to no avail. When the others got up, I got up too. Everyone went about their business: some to smoke, others to the computer. Nobody told me what to do. I would have liked to say: "Hello? I'm still here too! I'm human too!"

So I called Arlene: "Babe, what should I do? No one here explains anything to me." She advised me: "Just go through room by room, clean, change pads, put on fresh clothes and take people to breakfast."

It's at times like this that you realise: ultimately, only one person can help you - yourself. If no one shows you anything, your hidden potential will eventually come to light.

xyz

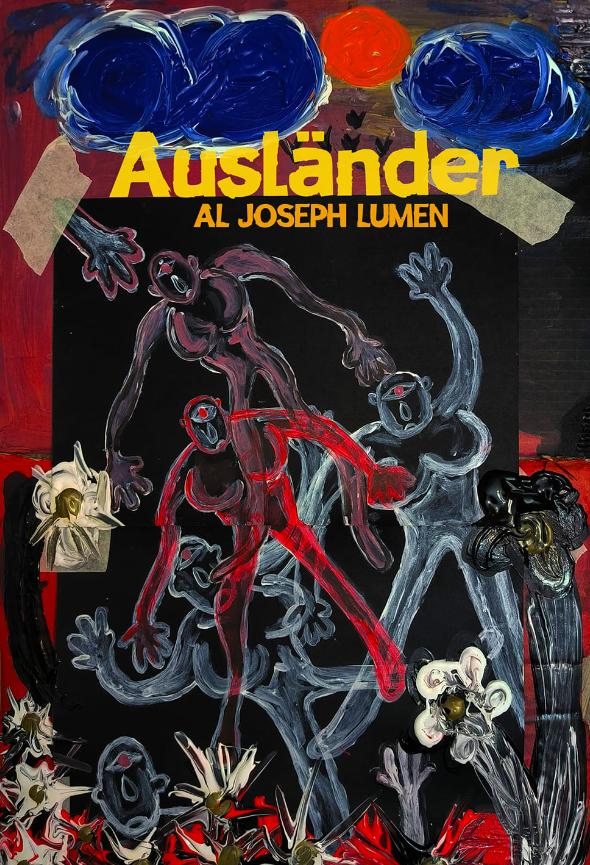

xyzAl Joseph Lumen | Ausländer: Mga Danas sa Alemanya | Balangay Books | 186 pages | 750 PHP

Go ahead and say I'm bragging - but every time I think back on it, I feel a little proud. I managed to single-handedly lift a bedridden old lady three times my weight from her bed to a wheelchair. Not bad, right? But no - it wasn't a miracle of strength, it was pure nervousness. I did this for two weeks until one day Arlene asked: "Why are you carrying Mrs. Gertisch on your own? Don't you know that there should be three people to lift her? Your back, Aljo - oh dear!" Since then, I've always asked for help.

In the past, at the BPO call centre, we were often told: Fake it till you make it. I never really knew what that meant. Pretend to be someone else? Pretend I know something even though I have no idea? That's exactly what I did, though: when I helped a customer, I pretended to dig deep into the problem - in reality, I was just reading the step-by-step instructions off the screen. I'd add a bit of drama, as if I was struggling - and the customers were happy.

One time, a guy called because he couldn't turn on his luxurious Motorola Razr.

"What colour is yours, Mr. Brown?"

"Black."

"Great, I have the red one. Let's both switch them off, then turn them back on together.

In reality, I only had an old Nokia 3210 with 30 peso credit - and the keys were already half worn out.

Another time, I was invited to an event. I told the organiser straight away: "I don't do spoken word poetry, ma'am. But I do know someone - would you like me to forward you their Facebook account?"

"You don't have to do spoken word poetry - just talk about your writing."

When I got there, I was suddenly told: "You're next, sir - spoken word poetry."

I felt as if someone had thrown me into ice-cold water. The topic was journalism - and now I was standing here, supposed to perform spoken poetry. The room was full - it was university week. I scanned the room for the teacher who had invited me - and would have loved to tear her head, albeit lovingly. I had said I wouldn't do that! There was no way out now - so I improvised.

I swaggered, put on a bit of drama - and lo and behold, people applauded at the end. To this day, I blush when I think about it. Because that's exactly what I hate: looking stupid - and still appearing confident - that's terrible! But I guess that's how it is: when you're already in the thick of it, you just press on. And occasionally, people even applaud.

But privately, I think the teacher only chose me to save money, because I didn't ask for a fee. The experience left me so ashamed that I didn't leave the house for a week.

(1) Chaka Doll is a colloquial Filipino term derived from the word "chaka" - a slang term for something ugly, unattractive or embarrassing. In pop culture in the Philippines, "chaka doll" often refers to a person (usually female) who wears excessive makeup or dresses flamboyantly, but is still considered tasteless or over the top.

My daily companion in the home was Chaka Doll (1) - that's what my Filipino colleagues called Glenda. Despite my best efforts, I hardly understood her - even years later. We only managed if she resorted to hand signals. Once she instructed me to clean and re-dress a patient's wound in room 102. The last time I had applied a bandage was at scout camp in elementary school - but I just nodded. Everything she said, I acknowledged with a "yes". Maybe that's why I was her favourite person to order around - I never disagreed.

Until the day she asked me to turn on a patient's oxygen. That's when my cover was blown. The patient became impatient: "What are you doing? Why can't you get my oxygen on? Aren't you thinking at all?" "Aren't you thinking at all? Aren't you thinking at all?" - his voice boomed. It was like a slap in the face. I almost felt like pushing the old man out of bed. It's like what we say at home: 'Use your brain!' Even though I didn't want to, I radioed Chaka Doll: 'Hello, can you please help me?"

"With what?"

"With... er... sauerkraut."

She explained something to me for ages - too quickly, too complicated. Then she asked: "Did you understand?" "Yes," I lied. I tried it - and the patient shouted even louder: "DON'T YOU EVEN THINK?!"

I radioed again:

"Hello, sorry... I don't know... sauerkraut... er... turn on."

I could already hear her heavy footsteps. She started vigorously pressing the buttons on the ventilator . She looked at me, reprimanded me. She and the patient were working together against me. Chaka Doll said something like sauerkraut, then oxygen. I didn't understand.

When I got home, Arlene said, "the Chaka Doll told you off, didn't she?" Her question sounded slightly mocking. Glenda had written to her and told me to learn German. And if I didn't know something, I shouldn't say I did, because I can always say I don't know something.

At home, I was exasperated, raising my voice: "I have no idea about this sauerkraut, why are there so many buttons to push!"

Arlene added that I made Glenda laugh because I kept saying sauerkraut. Then Arlene showed me what sauerkraut actually was.

"Babe, this is sauerkraut, and this is the oxygen."

Sauerkraut is pickled cabbage, and the oxygen is an oxygen machine. I had no idea. Over time, I was able to show off my skills to Glenda. I wanted her to notice that I spoke better German.

Since then, I practiced German extra diligently - especially with Mr. Bader, a friendly patient who was always smiling. This man was easy to talk to.

I would knock on his door: "Good morning, Mr. Bader!"

"Good morning!"

"Did you sleep well?"

"Yes."

"Did you have good dreams?"

"Yes."

The same scene every morning - and every time he had a work of art the size of a cowpat in his pad. Before I cleaned him up, I politely asked, "Are you a stool?" - which I thought meant "Did you have a bowel movement?". He always nodded amiably.

Until my colleague Rochel came in and asked with a laugh, "What do you mean - are you a stool? If the Chaka Doll hears that, you're fucked."

"Why? I'm just asking if he's already... you know."

"No, you're asking him if he's shit."

Mr Bader looked at us in silence as we stood next to his bed, laughing through our tears.

+++

Someone left

Yesterday was the first time I witnessed a patient die. Like a bird perched on my shoulder, the memories of Lolo Mike and Lolo David suddenly came flooding back - stories I had already told in another book.

My colleague - also Filipino - was also experiencing this for the first time. Neither of us had any idea what to do. Arlene had already told me that Ms. Zimmerman's relatives had been asked to visit her again. It seemed like a farewell. She had already been given morphine.

"Morphine? That's the really strong stuff... for cancer patients," I said in surprise. Apparently, her buttocks had swollen and eventually broken open - a liquid was leaking out. Arlene thought it was urine that had collected there, right at the spot near... well, down there. No wonder the room smelled like that when I brought her lunch the other day. I'd just flung open the window.

I'll never forget that old lady. She was one of the first patients I looked after on my very first day at work. Even then, she couldn't get up and lay in bed all day. A German nurse showed me how to prepare her breakfast - even though I didn't understand a word she said, I could interpret her gestures. Every morning, she said, Mrs. Zimmerman should be given bread that she could dip in coffee. And chocolate. She demanded it again and again in her soft but firm voice: "Chocolate, chocolate, a chocolate." Small treasures were stored under her cupboard - sweets and chocolate bars of all kinds. Sometimes I was tempted to take one for myself.

Arlene told me that Mrs. Zimmerman used to be quite mobile. She could walk, talk, even make plans. She had once said that once we were all here - Arlene, me, maybe even Isla - she wanted to meet the child and give her chocolate. But that never happened. One day she fell. They took her to the hospital, and when she came back almost a month later, she was a shadow of her former self.

"She used to be quite sturdy, babe" Arlene said. "I was shocked at how thin she'd become all of a sudden." No wonder I hardly dared to move her at first - one wrong move and I might have been blamed for her death.

If she had been an ordinary old lady in the Philippines, she would probably have died a long time ago. There, it's money that often prolongs life - medication is expensive. And here, ironically, I saw today how her remaining medication had been packed. Expensive brands, expensive preparations. I thought: damn, send this home - so many people could use it there.

When her buttocks broke open, there was talk of surgery. But the doctor said: "What's the point? She's too old. She wouldn't survive it." She was probably already over eighty.

Yesterday I was on duty with Rochel - she comes from Zamboanga and speaks Chavacano. "Aljo, she'll make it until tomorrow," she said. But I sensed that something was different. Mrs. Zimmerman's breathing was heavy, as if something was stuck in her throat - phlegm perhaps? In Germany, you can't just aspirate; the doctor has to agree first. And he would probably say: what's the point? So we raised her pillow so she wouldn't choke on her own phlegm.

Rochel leaned over to her: "Mrs. Zimmerman, are you all right?" No answer. I tried, "Would you like a piece of chocolate?" Again, no answer - just deep, rattled breathing. We took her blood pressure.

"I hope she doesn't die on us," Rochel muttered. "Otherwise we'll be in real trouble."

A few minutes later, we went back to her. I noticed immediately: she was too quiet. We looked - her eyes were open, but I couldn't see her breathing. A chill ran down my spine. We rushed out.

"Man, Aljo, I was scared!" shouted Rochel.

"Come on, we have to go back - she's probably dead."

I laughed nervously, but my heart was racing. We put on gloves and went back inside. No pulse.

We looked at each other - eye to eye.

In that moment, I felt something that's hard to describe. A strange silence.

I could hear the birds chirping outside, some program was chattering on the television, voices were murmuring in the hallway - and yet: a deep, unmistakable silence. So quiet that even the noise no longer made a sound.

I whispered to myself: "Someone has left."

+++

Did you enjoy this text? If so, please support our work by making a one-off donation via PayPal, or by taking out a monthly or annual subscription.

Want to make sure you never miss an article from Literatur.Review again? Sign up for our newsletter here.

These texts are part of the memoir Ausländer: Mga Danas sa Alemanya, which won the Best Book Non-Fiction at the 2025 Migration Advocacy and Media Awards. Ausländer: Mga Danas sa Alemanya is a collection of personal essays that recount the author's life as a Filipino migrant worker in Germany. It is also a personal memoir of a Filipino family's journey through the isolation of the pandemic and the challenging work they experience in a retirement home. It deals with themes such as the search for belonging, bridging distance and the relentless search for a home away from home. English adaptation based on the German translation from the Filipino by Elmer Castigador Grampon.

The original Filipino can be downloaded here: