This is the time after time

Beacon Press

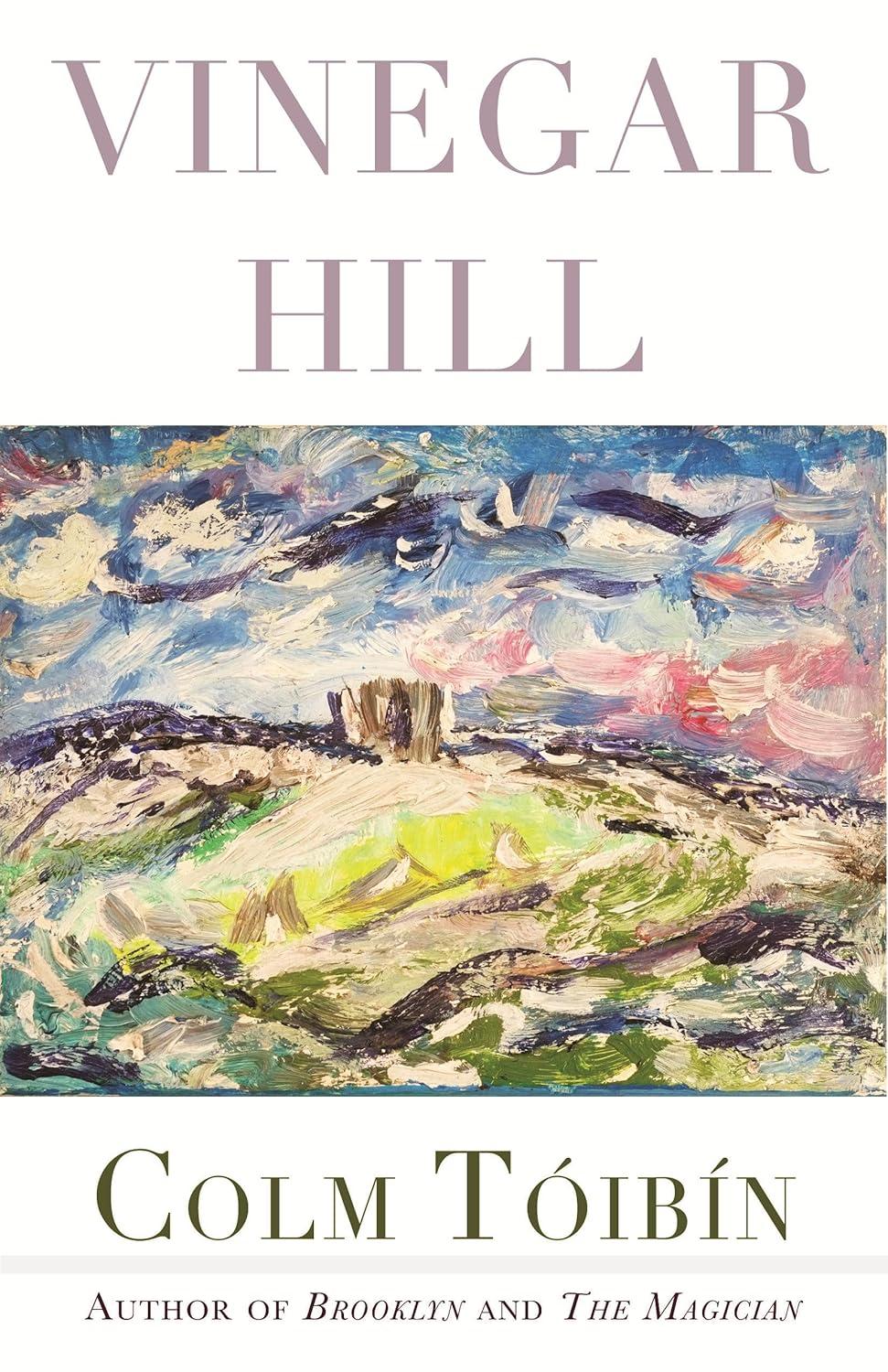

Beacon PressColm Tóibín | Vinegar Hill | Beacon Press | 144 pages | 22.95 USD

"Then retreat through hedges […]. Until, on Vinegar Hill, the final conclave. " With his "Requiem for the Croppies", from which the verses are taken, the Northern Irish born author Seamus Heaney, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, commemorated the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising against British rule in 1916 - which, despite its suppression, was a turning point on the road to Irish independence in 1922. Heaney drew a parallel between the Easter Rising and the Irish rebellion of 1798, when the Croppies, as the United Irishmen rebels were nicknamed, were defeated by the English crown at the Battle of Vinegar Hill after capturing nearby Enniscorthy. In doing so, he condensed the struggle for independence and the corresponding sectarian war between Catholics and Protestants into the religiously charged image of the last conclave. The fact that he frequently had to explain this is only in part due to his romanticisation of the rebellion - there is also an overt allusion: the Croppies of his "Requiem" begin their retreat to Vinegar Hill with barley in their pockets, which then grows from the earth of the hill where they were defeated and lie buried. This could have been interpreted by a Protestant audience, to whom Heaney sometimes read in the 1960s, as support for the IRA.

Among the ranks of Irish and Northern Irish writers whose literature addresses the freedom movement on the Emerald Isle, is the internationally renowned author Colm Tóibín. Vinegar Hill is his late-in-life poetry debut. However, his reason for singing about the historic hill is of a mundane nature. Tóibín was born in Enniscorthy in 1955 - the town is located in the south-east of Ireland in County Wexford, which borders the Irish Sea. As a child, the hill was ever-present: "We can see the hill from our house.", reads the childhood poem "Vinegar Hill", in which the events of 1798 are dutifully mentioned, but which is more about his mother as a budding painter: "thinking it natural to make/ The hill her focal point,/ Is trying to paint it ". This is a banal reason to take on the hill and relieves it of the burden of history. In its timelessness, it stands sublimely above history. Only the perception of the hill from the outside changes, as it is subject to the alternating relationships of shadow and light and the absence or presence of clouds: "What colour is Vinegar Hill? / How does it rise above the town?/ It is humped as much as round./ There is no point in invoking/ History. The hill is above all that,/ Intractable, unknowable,/ serene."

Resistant, unfathomable, serene; all attributes of the volume, evident in its various themes. The world from which they are drawn is post-catastrophic: the Irish question is at least partially resolved and dormant. It is post-apocalyptic: the pandemic is "the time after time,/What the world will look like when the world/ Is over ". And even a day like 23 May 2015, when the Irish population voted in favour of same-sex marriage, makes it clear to the two soon-to-be-sexagenarian gay friends that the vitalising resilience of being gay is history: "The years of excitement had gone:" They, and perhaps also Tóibín, who is openly gay, cannot join in the euphoria of the young queers; they feel the shame of being older and fall into the nostalgia of the "gay past", which they follow up with a meticulous mapping of Dublin based on the hangouts of the old gay scene "That have fallen off the map": "The city would become a map7/ Of another city/ That only they could read."

A series of poems thus reads like a rather melancholy meditation on the meaning of life and the passing of the individual through time. It can be ignited on journeys around the globe, in confrontation with film, art, literature and music, in Dublin's "dead cinemas" or in everyday occurrences such as a viewing appointment with a real estate agent, when time is divided into a before and an after: "Life and time, the original/ realtors, make us feel/ That all is change and flow".

The lyrical subjects are like the triply afflicted Gerard Manley Hopkins, "Englisch in Ireland, a convert/ To the Roman Church, a poet/ who is not in print", who answers the Irish painter John Butler Yeats' question of what life is with what life is precisely not. A question that is particularly acute for people with a particular awareness of death. Tóibín's obviously autobiographical poems feature an eight-year-old schoolchild who is told by his mother that his father will soon die: "From then I did not put my/ trust/ In anything much. When I/ summon up the names/ Of ones I love, for example,/ I recoil/ At having to whisper what/ has remained unsaid." An awareness of death that arises all the more in the face of one's own mortality: "If the chemo/ Zaps the tumour/ And doesn't kill me ". Tóibín alludes to his own cancer during the pandemic in a rather cheerful poem that illustrates an insight he expressed in an interview in 2022: "I love to say that I learned nothing from it, and that something is seriously wrong already if it takes a brush with cancer to teach you an appreciation of life."

But it's not as if Tóibín is just moping. The mockery that he heaps on Catholicism in his poems is full of humour and aggression, almost blasphemous. It concerns nuns who are finally allowed to drive and who, in their ignorance, transfer "Putting the fear of God/ Into other users of the road". A bishop, too, who is said to have died the day before John F. Kennedy's visit to Wexford, which encourages wild speculation and comparisons.

The only drawback of the translation is that it has not included all the texts from the original volume and has therefore omitted the poem "Prayer to St. Agnes", which is indispensable in that it sheds light on Tóibín's poetology: The lyrical subject there asks the saint to be cured of the metaphor. In this way, Tóibín opts for a simple poetic expression, which should be readily accessible in its message. He is entirely the narrator, transferring the narrative and dialogical character of his prose to the poetry, which emerges from a slim constellation of characters and events.

Tóibín's translators Michael Krüger and Volker Schlöndorff say that it was their way of rendering him a service of friendship, following the publication of the original English edition in 2022. It is also a service to passionate readers of poetry, who are delighted by the way in which identity and belonging, the private and the public, mortality and resilience, art and literature, here reflect man in all his complexity.