Risky freedoms

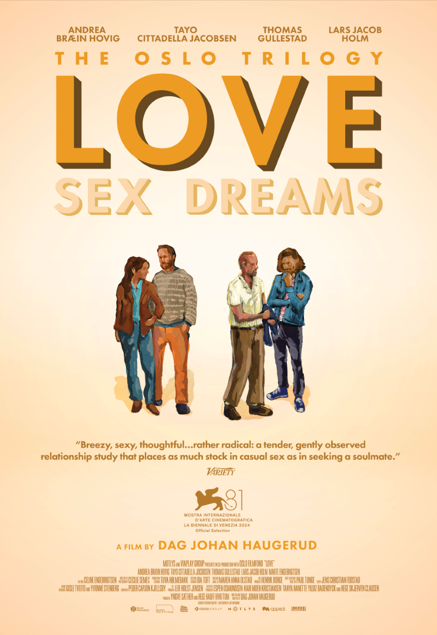

Love

Just like life itself, so too is Dag Johan Haugerud's trilogy. Quite simple and yet quite complicated. Because Love, the first film in the trilogy to be released in cinemas internationally, actually had its premiere in Norway at the end of 2024,, as the final instalment of the three. However, it's not like Haugerud's compatriot, Karl Ove Knausgård, whose five novels under the umbrella title Min Kamp have very similar subtitles to Haugerud's films, including one also called Love. But while Knausgård's autofictional books tell very similar stories about the winding paths that love and life can take in our time, each book builds on the ones before it.

Nordisk

NordiskThe Oslo Trilogy: Love | 2024 | NOR | 119 Min.

The same is not true of Haugerud's Oslo trilogy. Each film tells a separate story with different actors. Only one character -if it can be considered that - appears repeatedly; the city of Oslo. It is here that the protagonists' paths cross, all of them ending up at one point or other in front of one building in particular, Oslo City Hall, with its idiosyncratic sculptures that seem to promise fluid, unconventional relationships.

In Love, this building is central. It is where Marianne (Andrea Bræin Hovig) meets her friend Heidi (Marte Engebrigtsen), who is giving a guided tour of the town hall, explaining the fluid sexualities of the sculptures and thus also something like the Norwegian understanding of the human condition. This theoretical concept is, so to speak, put into practice by Marianne throughout the film. She works as a doctor on an oncology ward, treating men suffering from prostate cancer. Like the nurse Tor (Tayo Cittadella Jacobsen), who assists her in her consultations, she has no interest in static relationships but, like Tor, loves the fluid moments of life. She just lacks the tools to bring these moments into her own life. By chance, she meets Tor in a completely different context and learns from him what had previously been denied to her, while at the same time reflecting on every step she takes in long conversations not only with Tor, but also with the couples she meets.

In addition to Marianne's encounters, in which she makes it clear, among other things, that marriage as a unit of production is out of the question for her, Haugerud - until now best known for his fiction in Norway and outside the country his film Barn (2019), and who has also worked as a librarian - places just as much emphasis on Tor's romantic life, his homosexuality, which not only Marianne's patients understand better, but who also has and seeks other friends and ultimately comes from a different social class and from a region in Norway whose dialect is often mocked.

Haugerud intertwines these two lifelines, with all their fascinating ramifications, in great dialogues that, as in the two other films, last longer than ten minutes, but are so realistic that you don't want them to ever end. Haugerud's ensemble is delicately cast, right down to the smallest supporting role; all act as if their lives, or at least their love, depends on it.

Haugerud manages to capture moments of unexpected and profound tenderness, such as when Marianne pats the architect Ole (Thomas Gullestad), with whom she is to be set up by her friend Heidi, on his bottom as he enters through the window of his house, or when Tor overtakes Bjørn (Lars Jacob Holm) on his bike on the way from the hospital and tries to talk to him.

And then there are the words, the tenderness of language, the way in which knowledge is gained through talking, as in Heinrich von Kleist's essay On the Gradual Formation of Thoughts in Talking from 1805. In Love, this reflection descends into everyday depths, such as the mounting pressure of expectation from a distant letterbox or the conversation over a frugal supper in Ole's house on Nesodden. Every conversation leads to insights that are as easy as they are difficult. Because what counts is not always what is being talked about, but the very ability of each person to talk to one another at all. Only then does reality change for each of them, so it is only logical that the ending takes place in Oslo City Hall, where Love began. But of course, this is not an ending either, but rather the hint of a new beginning.

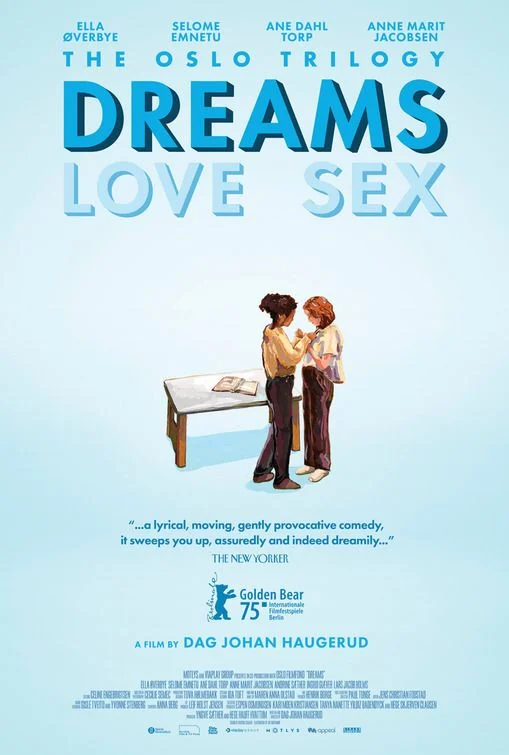

Dreams

At least in Dreams, the chronology makes sense. Dreams is actually the second part of Dag Johan Haugerud's Oslo trilogy. Whether Love or just Sex comes before or after doesn't seem to matter to distributors outside Norway, no matter how much Haugerud emphasised that Love was intended as the conclusion of his trilogy. For me, however, the trilogy also functions as a triptych with equal status, just as the individual paintings in Max Beckmann's work can also be interchanged and new conceptual intersections seem possible.

Nordisk

NordiskThe Oslo Trilogy: Dreams | 2024 | NOR | 110 Min.

At the same time, the international confusion fits in well with Haugerud's approach in his three films, where he places the almost inextricable complexity of human relationships, the depths of sexuality and the negotiability of social norms at the centre of his decidedly dialogue-driven films. While in Love it was adults of more or less the same age, in Dreams - which not only won the main prize at this year's Berlinale, but also the FIPRESCI and Guild Prize - Haugerud explores the thoughts, feelings and speech of three generations.

This may sound a little theoretical, but it is not. Haugerud's dialogues are so intrinsic to everyday life and at the same time cathartic, watching and listening to them one cannot help but feel genuine joy. Yet Dreams is perhaps the most complex film in the trilogy. The story unfolds slowly, almost imperceptibly. 16-year-old schoolgirl Johanne (Ella Øverbye) falls in love with her new French teacher Johanna (Selome Emnetu) and, in order to reaffirm and understand her feelings, she writes a text that she shows to her grandmother Karin (Anne Marit Jacobsen), who in turn shows it to her daughter Kristin (Ane Dahl Torp), Johanna's mother.

Although the film begins with a single theme - the crush or infatuation of a schoolgirl on her teacher - the manner in which it unfolds could not be less anticipated. This unfolding is best compared to tea leaves thrown loosely into a teapot and hot water being poured over them, a moment that we also witness in Haugerud's film, one in which one of the many conversations in this film takes place. The spoken word transforms not only the situation but also the knowledge of what this situation was and now is. These shifts in perception brought about by language are further reinforced by Johanne's text read from off-screen, which explores the past and combines the cinematic present, the flashback and the absolute present into a whole, catapulting us into an as yet undefined future.

We only see fragments of this future: a great scene with Johanne's therapist, in which not only the necessity of modern therapy and questionable suffering is discussed, but also where the present reconciles with the past, and Oslo City Hall, which plays a kind of anchor role in all three films, appears. Every word spoken here is finely calibrated. When Johanne's therapist addresses the banality of his client's suffering, Johanne manages to counter his plausible point of view with equal force, because she is right when she says: "If nobody wants you, you're nobody."

But Haugerud tells us much more. He speaks of the risk of losing control of our dreams and stories when they are shared. He speaks of the transformation of love in a changing city, and in a moving conversation between Johanne's mother and grandmother, they not only discuss flashdancing, but also three generations of feminism and womanhood. Here too, change is essential, although all change is also a miracle, because it also incorporates what was and what will be. This unity of what was, what is and what will be and the equally present disunity of speaking, acting and feeling are the essence, the tea leaves that unfold at the end, giving colour and taste to water and life.

Despite all the seriousness, Haugerud manages not to forget the playfulness and humour. The sometimes unbearable lightness of being is made bearable, not only through grotesque 'bon mots' such as the one about God being a naked Swede, but above all through the lightness and the need of all those involved to rid themselves of the heaviness of life through the act of speaking, thus becoming someone new. After all, this is perhaps the greatest promise of our modern age, that ultimately anything is possible, a freedom unknown for millennia that can finally be realised. In Dreams, but also in Love and Sex, Dag Johan Haugerud shows how this is possible. Touching, enlightening, fascinating. Great cinema. Great literature.

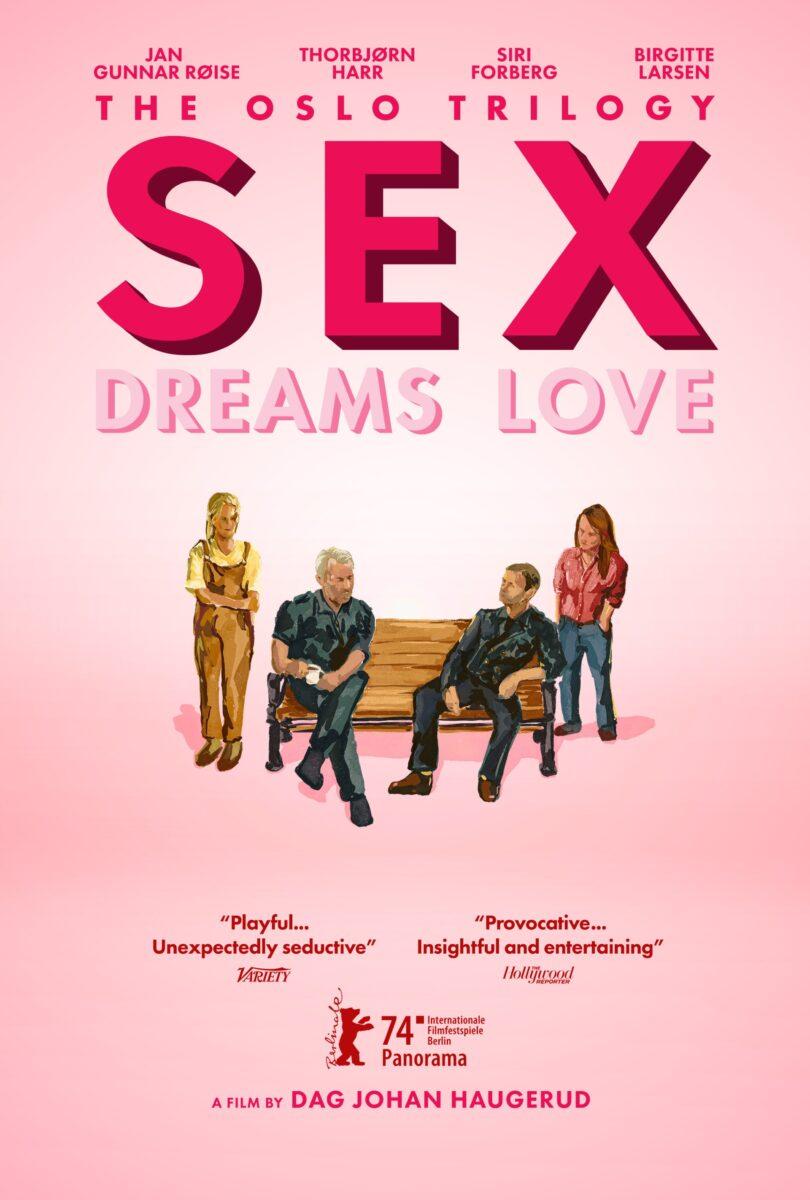

Sex

If I were to make films myself and not just write about them, they would be films like the three Oslo films by Dag Johan Haugerud. They are not just "literary" films, because they are interspersed with long dialogue sequences that, even without the camera and its images, tell absorbing, exciting and touching stories about our present and our most everyday feelings, even without the camera and its images: the possibilities of new relationship models in Love, the variance of relationships within three generations in Dreams and the fluid meaning of sexuality in Sex (which, curiously, in Germany is called Longing). This shows once again that Haugerud's films are indeed films of the word, of language, which repeatedly gains the upper hand over cinematic aesthetics and their pictorial language. Though not always.

Nordisk

NordiskThe Oslo Trilogy: Sex | 2024 | NOR | 118 Min.

This is evident from the utterly stunning first scene of Sex, in which two chimney sweeps sit together in their office overlooking Oslo's rooftops after their work is done. One is the manager (Thorbjørn Harr), who recounts a recurring dream in which he is confronted by David Bowie, who looks at him as no man has ever looked at him: without any expectations, or rather with an expanded expectation that he, the married man with a child, could also be a woman. His colleague friend (Jan Gunnar Røise), who also lives a hetero-normative life, then tells him about a similar experience. Not in a dream, but in real life; at his last customer's, he was looked at by a man for the first time in his life in a way that only women usually look at him, and what's more, was invited to have sex.

This conversation changes everything. Not only does it deepen the relationship between the two friends and colleagues, it also has a lasting effect on their partners, the chimney sweep's wife (Siri Forberg) and the managing director's wife (Brigitte Larsen). This core ensemble, including the couples' young children and friends, is increasingly drawn into this maelstrom of dreams and realities. This may be reminiscent of Arthur Schnitzler and his Traumnovelle and the Kubrick film adaptation Eyes Wide Shut or the German adaptation of Traumnovelle last year by Florian Frerichs, but Frerichs' film version is a particularly good example of how Schnitzler is hardly suitable for a truly contemporary adaptation. Anyone who disagrees should therefore watch Longing , as Haugerud shows both breathtakingly and tenderly what is possible in our (Western) present, and to what extent the act of speaking has acquired an almost self-therapeutic function for both sexes.

This includes not only the sexual relationships discussed here, but also the relationships between friends and between parents and their children. Although the language central here too, you could listen to this film spellbound even without its images.

But when you see the images and the great actors of these finely crafted characters, worked out down to the last detail, you almost feel compelled to step into the screen, just as Tom Baxter once stepped out of the screen in Woody Allen's The Purple Rose of Cairo. Because Haugerud's reality not only surpasses in its authenticity any actual reality, but is also so much smarter, more beautiful and better. Be it the scene in which one of the chimney sweeps visits a speech therapist with his son because the David Bowie dream triggered a speech blockage, or the long conversations between the couples, or the visit to a choral concert. Just as in Sarah Polley's documentary search for her biological father in Stories We Tell, you feel an urge to meet the characters in Haugerud's film, to talk to them or, ideally, spend an entire evening or a lifetime with them.

Haugerud shows that the world is the way you talk to it, the way you talk to your neighbour. However, the price for this is high - it is a freedom that is always associated with risk, with possible failure. And it also hurts because conversations, this struggle with language and our relationships, is always a struggle with the truth. With the external truth and with our very personal inner truths, which must always be reconciled. However, the possible prize is then to experience the most beautiful thing of all, namely to be seen by the others around us without expectations and to be able to be who we want to be. To be someone completely different, even if only for an afternoon with a customer in their home, in front of a freshly swept chimney (whereby the fundamental and very humorous symbolism of "chimney sweeping" should not be ignored). Just as Haugerud subtly breaks with expectations in his films. After all, who expects such reflective conversations from chimney sweeps, such profundity from a schoolgirl in Dreams and such an unconventional search for a love relationship from a doctor as in Love?

At the end and in the middle of Sex, we find ourselves back at Oslo City Hall and perhaps think we see the other wonderful people from Love and Dreams in the crowd filing past. Are they there or not? But even if they are not, the possibility is enough. Just as Haugerud's films are also the entirely real possibility of literature turned into film.