Pompeii lies on the Baltic Sea

Love's gonna make us, gonna make us blind

We'll be living in a place we like

What's gonna make us, gonna make us find?

- Wallners, In My Mind

It is becoming increasingly rare for a writer, artist, musician or director to stay with us for half a lifetime or even longer. The decreasing attention span with the almost endless possibility of media consumption means that things that have been familiar for a long time simply tip away almost imperceptibly - out of sight, out of mind - so that the sustainability of fame has become increasingly fragile.

But fortunately there are a few exceptions. One of them is Christian Petzold, who has been making films for a quarter of a century that have always operated subtly and with their finger on the pulse of the times, revealing social gaps and abysses and surprising us time and again with their unique visual and formal language. Be it Die innere Sicherheit (2000), Wolfsburg (2004), Jerichow (2008), Barbara (2012) or Phoenix (2014). With Phoenix, however, a symbolic heaviness and a compulsion to stylize had already crept into Petzold's feature films (from which the police calls were excluded), which in the Anna Seghers adaptation Transit (2018) and in Undine (2020) became so strong that Petzold's greatest strength, namely telling big emotional and social stories through the small everyday lives of his protagonists, became smaller and smaller and the plot and its characters seemed to literally freeze under the dictates of a big idea.

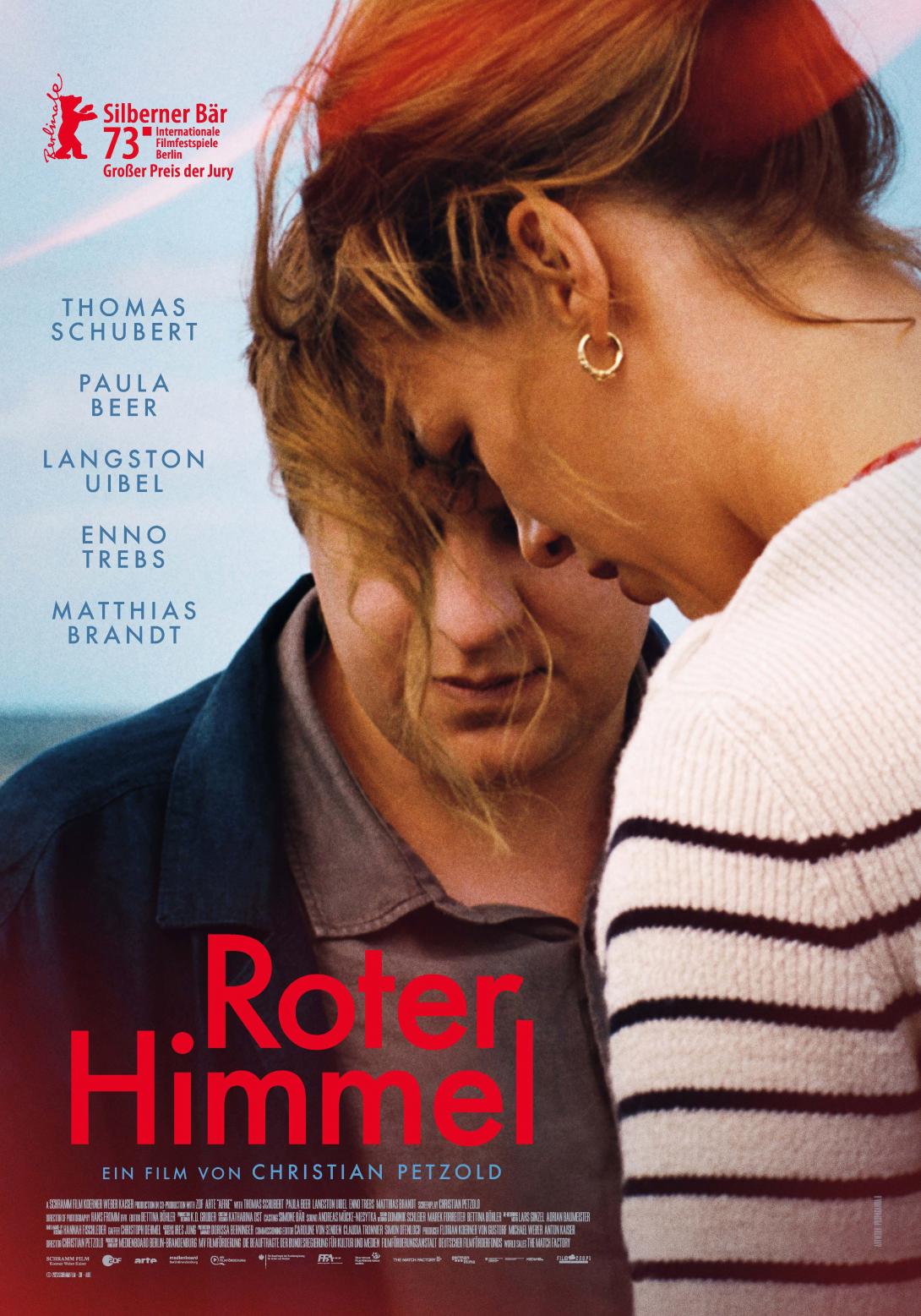

Piffl Medien

Piffl MedienRed Sky | Director: Christian Petzold | DEU 2023 | 103 minutes

Although Petzold's new film Red Sky is the second part of a trilogy, it has a lot in common with the first part, Undine, only the rather vague and contrived trilogy idea - from water to fire to earth or air - that Petzold's Gespenster-Trilogie already had in common. And one of the main characters. After the German-mythologically charged water creature and water in general and a great Paula Beer in Undine, it is now once again a subcutaneous, almost somnambulistic Paula Beer, who this time is not surrounded by water, but by fires on the Baltic Sea. Otherwise, there is hardly any sign of dripping German mythology. If anything, Red Sky is imbued with the poetic realism of a Fontane - which was also used in Emily Atef's Irgendwann werden wir uns alles erzählen - and the threatening gestures of nature (and in this case, a broken-down car), which knows more than humans; the drama is therefore in the room from the very beginning.

Unlike Atef, however, this is almost irrelevant in Petzold's film, because Petzold tells extremely light, seductive and funny love stories amidst all the apocalyptic fires that actually threaten the German Baltic coast in 2022 and during filming. It's a bit like Eric Rohmer's relationship roundelay, in Pauline on the Beach or Summer, by which Petzold was also inspired, and it's a bit like Shakespeare's Sommernachtstraum and Goethe's Wahlverwandtschaften - two couple constellations meet and the relationship dynamics wonder and transform. If this is a bad thing in Goethe's work, it is a good thing in Petzold's. We are watching young people, who will soon be in their thirties, in their late coming-of-age, and of course this is also a classic Bildungsroman. Leon, wonderfully embodied by Thomas Schubert as the lumbering Tor, who has come to his mother's summer house with his friend Felix (Langston Uibel), finally wants to finish his second novel and Felix wants to get his photo portfolio ready for art college. But Nadja (Paula Beer), who has surprisingly also been assigned a room in the house by Felix's mother, not only upsets the constellation with Devid (Enno Trebs), who occasionally spends a night with her, but is as somnambulistic as Leon, who increasingly loses control in her presence.

Petzold arranges this relationship roundelay extremely delicately, every dialog is perfectly pitched and despite all the heavy art, the light life is never far away, there are discussions about whether roofing or supermarkets are better, there are wonderfully parried, dialogues that enhance the situational comedy, badminton is played at night with glow sticks and when Leon is almost forced to go to the beach, he doesn't go swimming but reads Robert Schneider's utterly ripped novel Schatten. This is, of course, an almost corny allusion to Leon's own novel, which Nadja will proofread at some point and Leon's publisher Helmut (Matthias Brandt) will discuss with him. This visit is also wonderfully framed, with Uwe Johnson and the Aarenshoop artists' colony suddenly on board, and the snarky and seductive Nadja actually becomes someone completely different once again, she is questioned just like art and life in general.

However, these questions are only touched upon by the looming fire, they are play and fun, a game above all of bodies and then also of minds, between desire and reason, symbolism and realism, comedy and tragedy.

Petzold manages to maintain this balance so playfully right to the end that it really is a joy, a constant discovery and surprise, even Christian Petzold's almost iconographic woman on a bicycle. The wonderful thing about this woman, about Nadja, is actually her bicycle and everything that goes with it, the ride to work, the shopping, the banal disappearance; that she is not like the women in Transit and Undine is "femme-fatalistic" and immanently charged by the system, but is completely everyday and only a little bit mythical in the sense of François Truffaut.

As is so often the case in Petzold's films, Red Sky also has a little twist, a quick and final flirtation with melodrama - which is also reminiscent of this week's other summer film, which also screened in competition at the Berlinale but didn't win a Silver Bear, Emily Atef's At some point, we'll tell each other everything. But here it's not a train track, but the great story of the fall of Pompeii and its lovers. But this also fits, blending into the narrative as elegantly and surprisingly as a well-written novel whose artistry not only amazes you, but which you want to read again. Even more so when Petzold manages to reinvent himself a little at the end by not only alluding one last time to the Wallners' hypnotically lascivious In My Mind, but also adding an ending, a wonderful puzzle that unites literature with film, because one arises from the other and vice versa. It could hardly be more beautiful, lighter or heavier.