The myth and compassion

Netflix

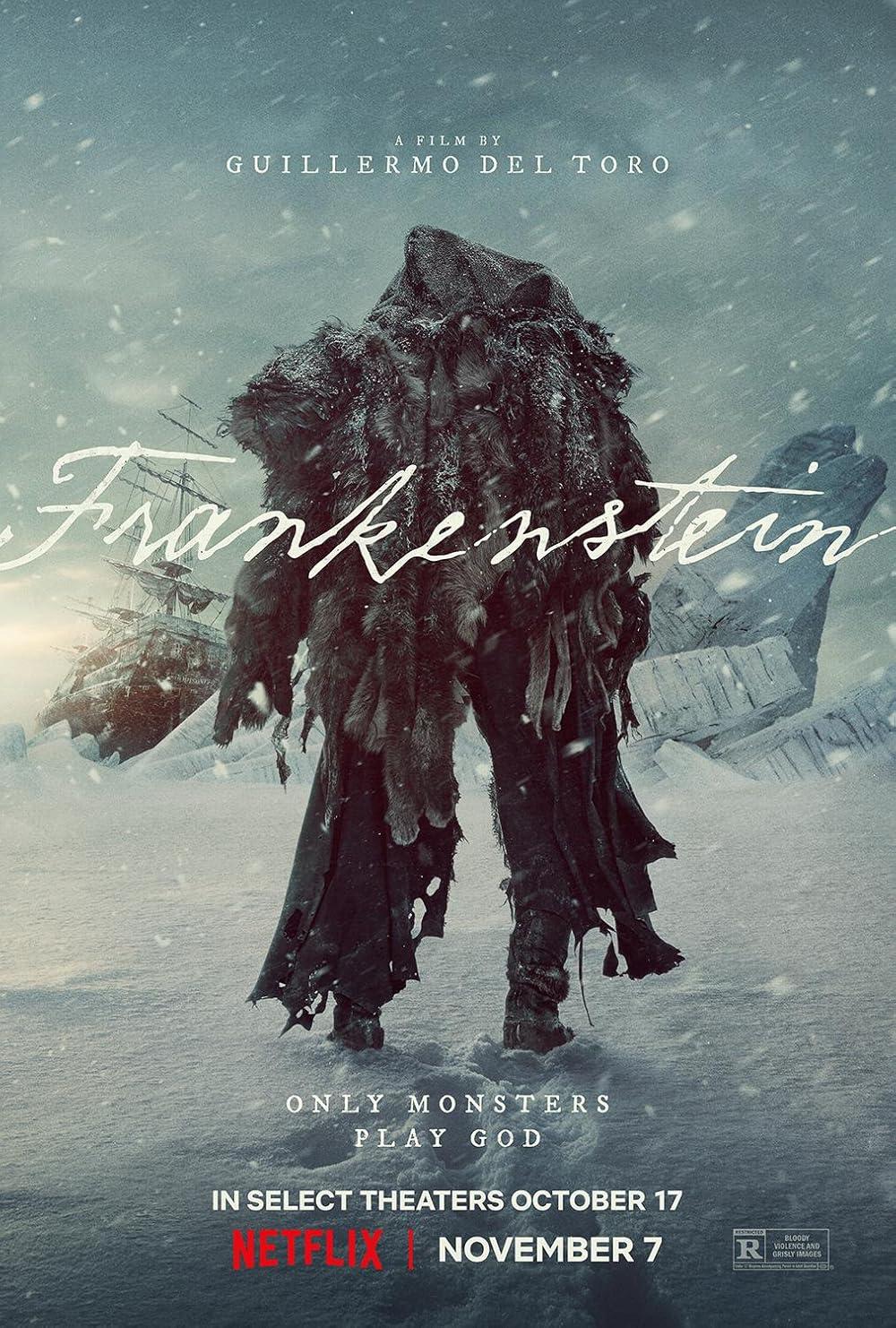

NetflixGuillermo del Toro | Frankenstein | 2025 | USA

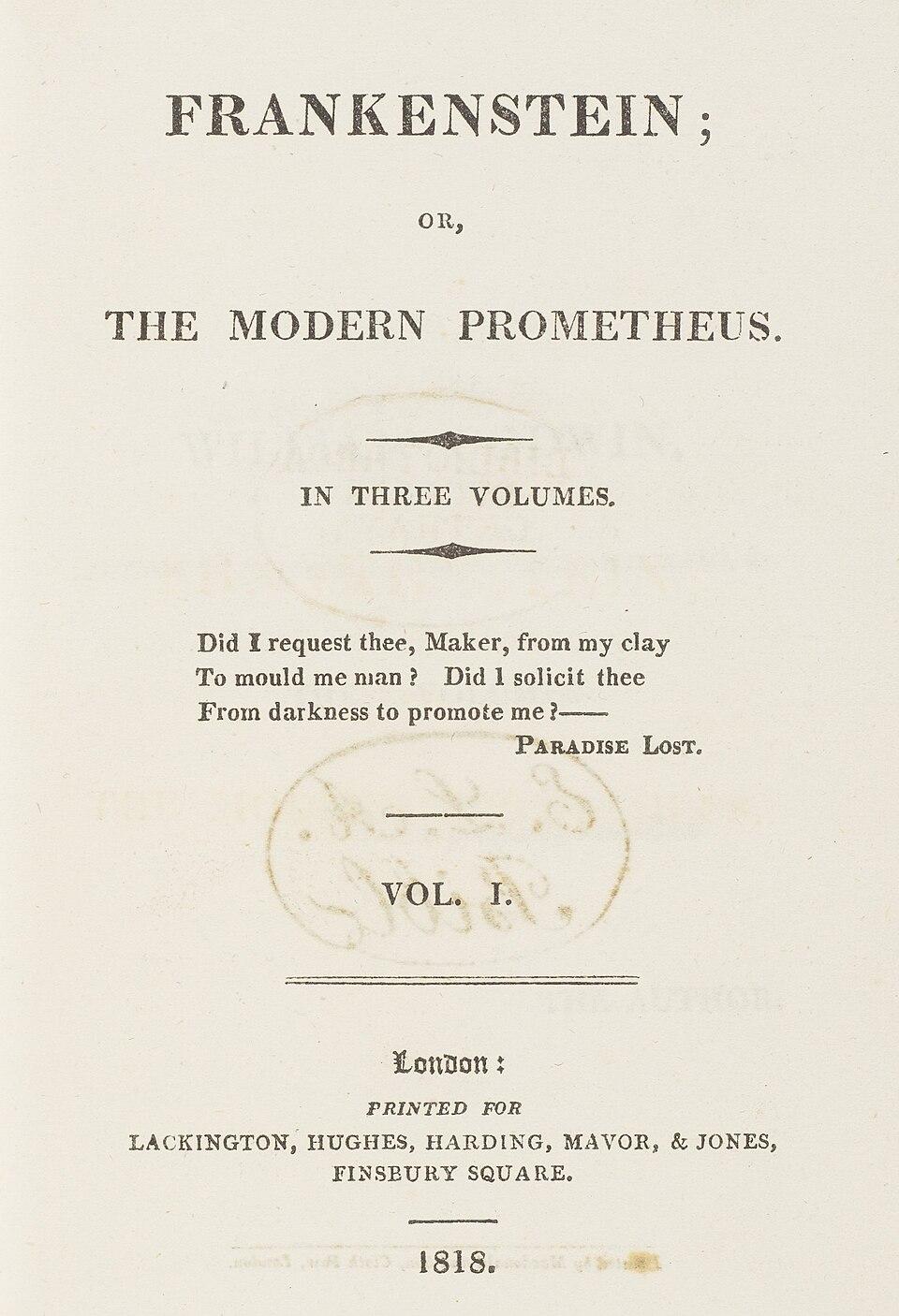

There are subjects that are accessible like sediments of a collective consciousness. They cannot be reinvented - only revived. And who better to do this than Guillermo del Toro, the great restorer of monsters, the anthropologist of otherness? Even with his Pinocchio (2022), we wondered why another version of this over-dramatised fairy tale by Italian author Carlo Collodi was needed - until del Toro proved us wrong. So now Frankenstein, based on Mary Shelley's 1818 novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. A theme that seemed to have been exhausted, over-staged, quoted and parodied like no other. And yet del Toro achieves something truly surprising: He reanimates not only the monster, but the myth itself.

Film history boasts over a hundred cinematic adaptations, from the first, in 1910 -the barely twelve minutes long Edison version, through James Whale's canonical Frankenstein adaptation from 1931 with Boris Karloff as the iconic creature, to Kenneth Branagh's baroque, hyperventilating 1994 Mary Shelley's Frankenstein. There's the British Hammer era with Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee, Mel Brooks' bizarre parody Young Frankenstein (1974) and the countless travesties, remakes and animations that extend to Tim Burton's melancholy Frankenweenie (2012). Even Yorgos Lanthimos' Poor Things gave the Frankenstein myth a feminist update with its grotesque parable of emancipation. One might have thought, then, that the final nail in the coffin had been hammered in.

But del Toro has patience. He had been dreaming of making Shelley's novel into a movie since 2007. He was waiting for the "right circumstances", the necessary emotional urgency for the work to be fully realised. Now, almost two decades later, this dream has become a reality. And just as del Toro's Pinocchio is no longer an adaptation of a children's book, del Toro's Frankenstein is no longer a horror film in the classic sense, but a Miltonian tragedy, as del Toro himself says - a religious, deeply personal work of confession about creation, guilt and shame.

Oscar Isaac plays Victor Frankenstein as a manic yet sensitive demiurge who's wish is not to change the world, but to conquer death. His laboratory is both cathedral and torture chamber, a place of transcendence where man plays God, or challenges him. Christoph Waltz embodies Heinrich Harlander, the wealthy patron who finances Frankenstein's experiments - a cold cynic with the unwavering self-assurance of those who believe their money can buy immortality. Del Toro draws a surprisingly contemporary parallel here: Harlander is the prototype of Musk's Silicon Valley billionaire, who cultivates his own future in a laboratory. Artificial intelligence thus becomes the moral continuation of Frankenstein's hubris - the age- old dream of eternal life in digital form. But of course these are only moments; del Toro returns just as quickly from the future to land back in his manic-depressive, almost dark romance-like illuminated past of the mid-19th century, a deviation, in narrative terms, as far from the original as was his Pinocchio.

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia CommonsMary Shelley | Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus | 1818 | 280 pages

In Frankenstein, Guillermo del Toro makes deliberate use of deviations: his film scenario shifts crucial elements - for example, the relationship between Victor and Elizabeth changes significantly: in Shelley's novel, Elizabeth and Victor have been closely linked since childhood, Elizabeth described partly as an adoptive sister and partly as a cousin; in the film, however, she is given a more complex dual role and greater independence. The frame story is also modified: While Shelley narrates her novel via framing prose by Captain Robert Walton, reflecting Victor and then the creature, the film takes up this structure but changes it in setting and narration - with, for example, an Arctic expedition as an introduction. In addition, del Toro expands the biographical background: The film features a dominant father figure (Baron Leopold Frankenstein) and shapes Victor's childhood through extended family constellations - aspects that are at best hinted at in the novel. Finally, del Toro also changes the motif spaces: in the film, for example, an aspect of the father-son relationship and technical entrepreneurship comes more to the fore (for example through the aforementioned patron Heinrich Harlander, reminiscent of Elon Musk), which Shelley did not develop in this form.

And the monster, embodied by Jacob Elordi with almost biblical grace, is no mere monster, but a sentient being who experiences his own creation as a metaphysical trauma. His birth is a crucifixion, his awakening a moment of resurrection: between Christ's pose, flashing lights and a storm of machinery. Del Toro choreographs this moment as a sacred spectacle. While the thunderstorm rages outside, the body rises in a choreography of pain and light - a macabre yet tender dance of life.

A little later comes perhaps the film's strongest part: the monster's second awakening in front of the mirror, his incarnation. A silent moment, a kind of mirror stage according to Lacan - the creature recognises itself for the first time as an entity, a self, a body. Here, del Toro not only quotes psychoanalysis, but the birth of consciousness itself. And all at once, we realise that this monster is not only a victim, but also a subject - capable of love, of thought, of grief.

Like Mary Shelley in her novel, del Toro interweaves religious and mythical layers with the dialectic of creator and creature. The dialogues echo lines from John Milton's Paradise Lost, the work that inspired Shelley herself: "The horror of the truth - to be not of the same nature as men." The creature is a fallen angel, Lucifer and Adam at the same time, rebel and son longing for his father. Del Toro translates Milton's themes - rebellion, free will, knowledge and guilt - into a cinematic theology.

Visually, Frankenstein is overwhelming: the foggy, storm-lit Europe; the bloody, corpse-strewn battlefields where Frankenstein finds his raw materials - accompanied by the eerie, lulling elegance of a waltz that dances over the corpses. You can sense del Toro's obsession here with bodies and materiality, with the weight of flesh and metal, with the intersections between Eros and Thanatos.

Yet despite all this dark beauty, del Toro's Frankenstein also becomes a love story towards the end - between creator and creature, with homoerotic undertones, between father and son, victim and perpetrator. When Elordi and Isaac confront each other on the ice (and later on the ship), surrounded by the infinite whiteness, the metaphysical hunt suddenly becomes a gripping melodrama. Here, del Toro echoes Melville's Moby Dick - Frankenstein's hunt for his creature mirrors Ahab's hunt for the whale: a duel with one's own shadow that can only be resolved in death. A literary motif that, incidentally, was published at almost exactly the same time as del Toro sets his story.

Lars Mikkelsen as Captain Anderson frames the story with an expedition to the Arctic, that place of emptiness where man is tested to his limits. Del Toro's use of this framing narrative is almost more convincing than Shelley's in her novel: the ship, frozen in ice, becomes the stage for the end, but also for forgiveness. When the monster stands in the last light of the sun, tears running down his face, it is no longer Karloff's silent mourning from the thirties, but a reincarnation - a reminder that even the monster is human and therefore has a future. Self-destruction is no longer necessary.

Mia Goth as Elizabeth Lavenza - who also plays Claire Frankenstein - lends the film a dual feminine perspective. She is lover, mother, echo, ghost. The themes of birth and death, love and sacrifice merge in her. Del Toro, who has always presented the female characters in his films as guardians and bearers of knowers, makes her the emotional centre - a quiet counterpart to Viktor's male hubris.

The fact that del Toro refers to Shelley's text as a "religion" is not a pose. His reverence for the source is palpable in every shot, his love for the stories that made cinema possible in the first place. Frankenstein is therefore not a revival, but a sacrament: a ritual of revival - of the myth, of the genre, of the belief in the empathy of the monster that ultimately resides in each of us.

What in Branagh's film dissolved in baroque effusiveness, del Toro finds an almost liturgical calm as the film progresses. He directs with pathos, but a pathos of seriousness, not kitsch. When sun and ice, death and tears collide at the end, we witness perhaps del Toro's most honest moment: the monster weeps - and the viewer can finally weep with him. Because at this moment, he also realises that Frankenstein is not a horror film, but a film about the human condition itself. Guillermo del Toro wrests Frankenstein from the gruesome, the horror, and instead creates a story of resurrection, a story about creation and its loneliness, about guilt and redemption, about the power of compassion in the face of darkness. A film that returns a powerful vitality to cinema, something that, along with literature, many have declared dead.

+++

Did you enjoy this text? If so, please support our work by making a one-off donation via PayPal, or by taking out a monthly or annual subscription.

Want to make sure you never miss an article from Literatur.Review again? Sign up for our newsletter here.

Guillermo del Toro's Frankenstein will be released on Netflix on November 7, 2025 after a release in selected theaters.