At the very bottom

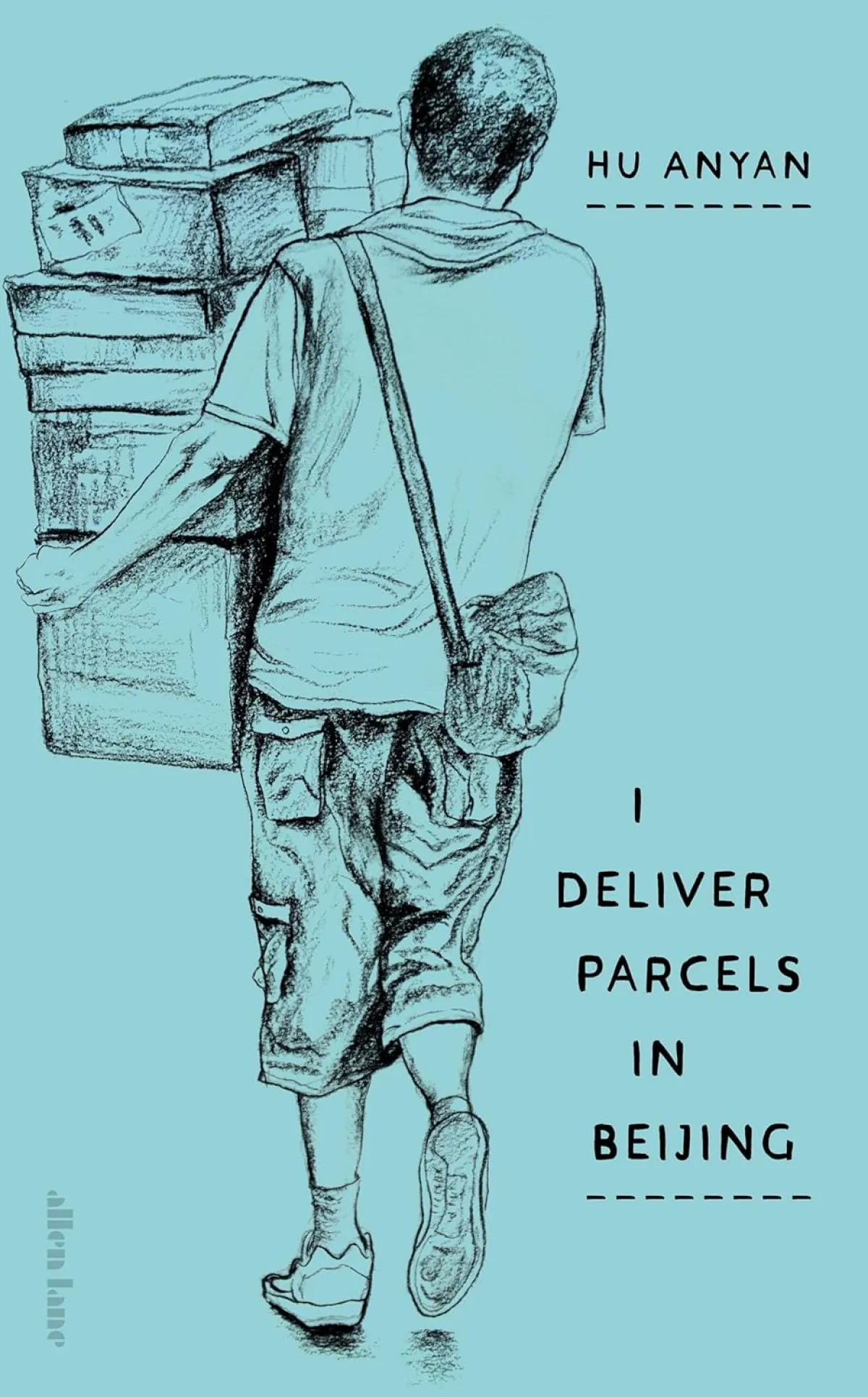

Hu Anyan | I Deliver Parcels in Beijing: On Making a Living | Astra House | 17,99 EUR

Hu Anyan is - or rather, was - one of around 200 million so-called gig workers. Like modern day labourers, they move from city to city, job to job, oiling the cogs of the Chinese platform economy with their work in the low-wage sector. Anyan has held 19 different jobs in 20 years. He has worked as a baker, in a petrol station, as a waiter, in mail order, in a bike shop and as a delivery driver. With this background, he represents one of the more stable types of worker in this environment. For some years now, Hu Anyan has been living with his wife in a small apartment, one of more than 20 million inhabitants of the Chinese provincial city of Chengdu. His autobiographical text about working in the low-wage sector was published in China in 2023 and hailed by readers as a major event. Since October 2025, the book I'm Delivering Parcels in Beijing has also been available in English and German translation.

Hu Anyan's dispassionate description of precarious everyday working life in modern China is reminiscent of literary naturalism; Gerhart Hauptmann, Émile Zola and Maxim Gorky, and Upton Sinclair's moving novel about slaughterhouses, The Jungle. However, unlike the authors of the 19th and 20th centuries, Anyan never gives the impression that he is addressing social issues as questions about the state of society. Admittedly, individual bosses and sometimes even a female boss behave quite unpleasantly towards their employees, but the system itself is never questioned. It doesn't even peek through the surface of the text - at least not for Western readers.

Anyan's book quite obviously ignores the social dimension of the topic. It doesn't ask who profits from this rampant platform economy. It doesn't accuse the number-driven optimisers and cost-cutters at company headquarters. It doesn't mock the apparatchiks of the omnipresent party. Presumably this is the price one has to pay in order to create anything resembling a counter-public in the propaganda-saturated public sphere of the People's Republic. The book's success with Chinese readers seems to justify this approach.

In Anyan's book, the individual runs in his hamster wheel - day in, day out. The delivery driver in present-day Beijing is barely distinguishable from a Kafka character in central Europe, a hundred years earlier. An anonymous power rules over him and his life. But this power is elusive - at least for the narrator. In fact, Hu Anyan began reading books more than fifteen years previously in his few spare moments and years later, recounted in an interview that the characters in Musil and Kafka had particularly touched him., you could say, has left its mark on his writing. Today's gig workers also seem to be at the mercy of an intangible force, a faceless apparatus - algorithm-controlled technology.

Chinese platforms control their drivers via apps, GPS and algorithms. In the competition for market share, every minute counts. Hu Anyan objectively calculates the impact of the platform economy on his work: "Our regular working hours were '996', or in other words, we were available from nine in the morning until nine at night, six days a week." According to his estimates, a delivery driver needed 7,000 yuan a month to survive in Beijing. With around 26 working days, that was 270 yuan per day, or 0.5 yuan per minute, after deducting loading and driving times. To avoid making a loss, he therefore had to successfully deliver a parcel every four minutes. "If one minute was worth 0.5 yuan, then peeing cost one yuan," Anyan calculates, "but only if the toilets were free. A lunch took twenty minutes - ten of which were waiting for the food - so it was 10 yuan time cost. A simple dish of rice and meat cost 15 yuan. Too extravagant for me! So I didn't usually eat lunch. To cut down on toilet breaks, I hardly drank anything in the morning."

Those who read the book primarily from a literary perspective will be rather disappointed. Hu Anyan belongs to is a documentary tradition that gives an authentic voice to the voiceless without placing huge importance on sophisticated dramaturgy or modern narrative styles. He opens the world's eyes to a precarious, thoroughly conflict-laden aspect of Chinese society that is rarely addressed in geopolitical debates.

Did you enjoy this text? If so, please support our work by making a one-off donation via PayPal, or by taking out a monthly or annual subscription.

Want to make sure you never miss an article from Literatur.Review again? Sign up for our newsletter here.