Reality as conjecture

Tlotlo Tsamaase is an author from Botswana (xe/xem/xer or she/her). Tlotlo was a finalist for the Caine Prize. Her novella The Silence of the Wilting Skin was a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award 2021 and was shortlisted for the Nommo Award 2021. Tlotlo's short stories are published in Africa Risen, The Best of World SF Volume 1, Clarkesworld, Terraform, Africanfuturism Anthology. She has a bachelor's degree in architecture from the University of Botswana and won an award for design architecture.

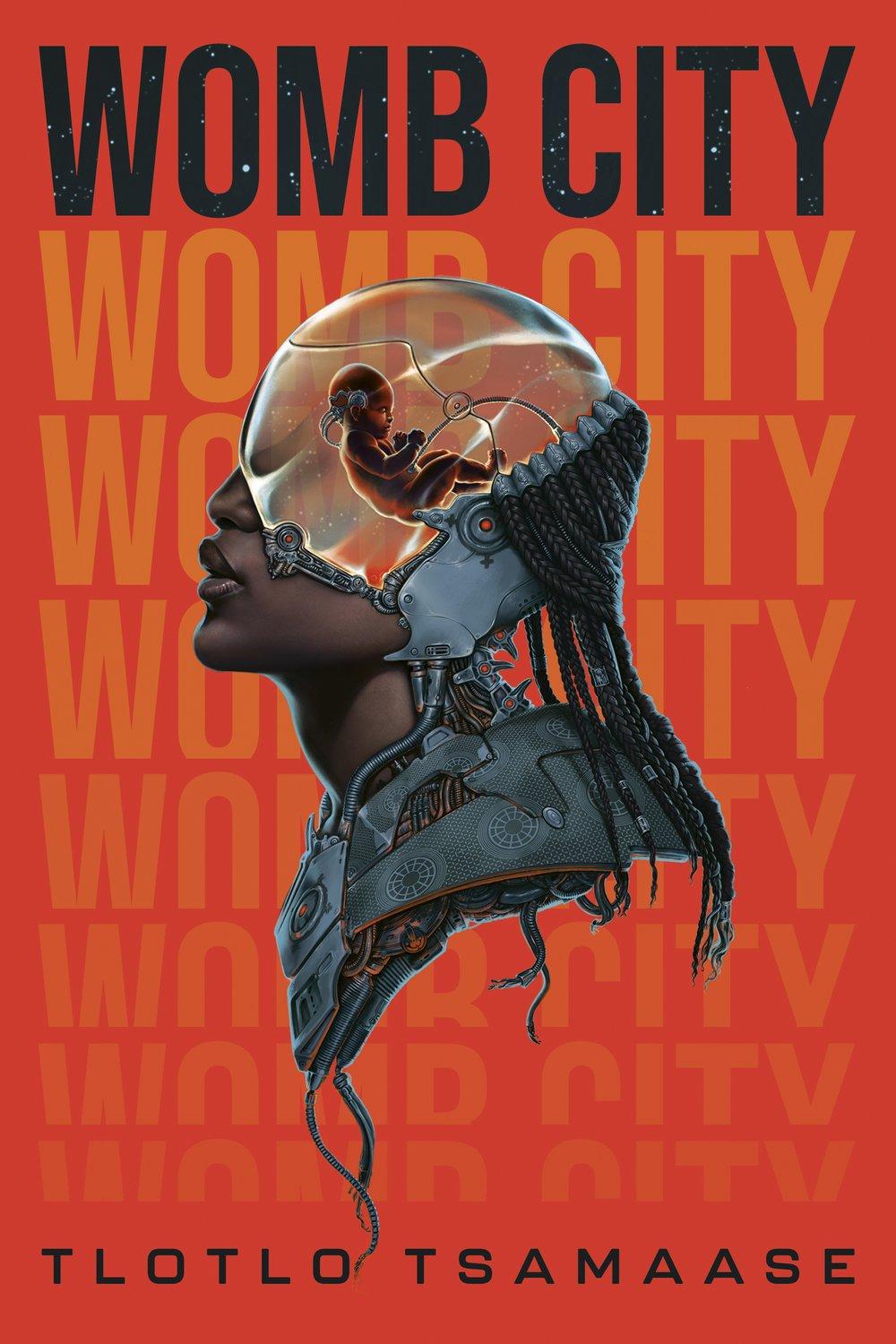

If you remember the legendary African Writers Series, have maybe even read a few volumes, or at least the first, Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart, published in 1958, then Tlotlo Tsamaase's Afro-futurist dystopia Womb City will come as no surprise. After all, as in Things Fall Apart and many other volumes in this series of great classics of African literature, it is about identity. Specifically, the loss of identity and the development of a new one. This is often related to colonial experience, but also to the question of how to integrate tradition with modernity.

However, the modernity conjured up by Tlotlo Tsamaase is not part of a recognisable past or present, but rather a future in which Africa is no longer the ugly duckling of the global world order, but a beautiful white swan who uses innovative technologies to create societal structure. As in Richard K. Morgan's cyberpunk milestone Altered Carbon, this also includes the possibility of transferring one's personality into a new body if the old body has exceeded its "shelf life" or is no longer viable as a result of accident or violence. But unlike Morgan, whose brutal future has little to do with our present or past, Tsamaase builds traditional elements into her future, intended to give society a solidly grounded identity. This includes a technical singularity that incorporates the spirits of the deceased and that is consulted on important political decisions. As in Spielberg's Minority Report, not only does this singularity know more about people than they themselves do, but the police in Tsamaase's Botswana are also able to determine, through regular virtual testing, whether or not a citizen could become a criminal in the near future.

Nelah, the narrator and heroine, is aware however that this Botswana, like Achebe's Nigeria, suffers from a broken identity: "In our city, it is unwise to trust reality. I have been betrayed by reality, betrayed by my subconscious, shipwrecked from reality." And like Achebe's tragic hero Okonkwo, Tsamaase's heroine - already "incarnated" in her 13th phase of life - rebels simultaneously against past and present, tradition and modernity.

The auspices are quite different though, because of course the Botswana in Womb City is far removed from Achebe's small village; almost 70 years have passed since Achebe wrote his novel and many hundreds of years in Tsamaase's story.

We are also dealing here with a strong woman who is fighting for her rights as a woman, in a society that, despite proclamations of equality, is permeated with the views of old traditions, where having children is just as much a dictate as it still is in many African societies today; a society in which black male elders have all the power and corruption is rife in a system that is loathe to admit that change must happen for the status quo to remain.

Erewhon

ErewhonTlotlo Tsamaase | Womb City | Erewhon Books | 416 pages | $27.95 USD

Tsamaase packs these heavy, dark manifestations of a failed dream into a thriller that is also a love story and a tale of marital crisis, playing with elements of body horror as well as classic suspense. With the emancipation of her heroine, for whom Tsamaase repeatedly finds bizarre, impressive images, situations and brilliant mind games that stay with the reader for a long time due to their intensity, Tsamaase also frees herself from her influences in the last third of these 416 pages; eventually cyberpunk and Spielberg become just a minor matter. Because Womb City also obliquely plays contemporary political dilemmas off against each other and opens up exciting new, refreshingly critical perspectives on so-called Afro-futurist visions, which are of course just as applicable to the Global North as they are to the South.

The new world that is ultimately heralded in Womb City is one in which tradition is eradicated by tradition and only through the resulting silence and purity has something like the future become possible at all. A future that transcends singularity and social bubbles, which have always been and will be yet for us readers, more prison than secure freedom. It is a future with a heroine on the front line, self-empowered not only in body but also in spirit, who fortunately does not share the same fate as Achebe's hero.

This not only has literary-historical impact, but also shows a radical author at work, confidently cutting through the tiresome expectations that most readers are likely to have of sub-Saharan culture.