Our share of happiness

Penguin

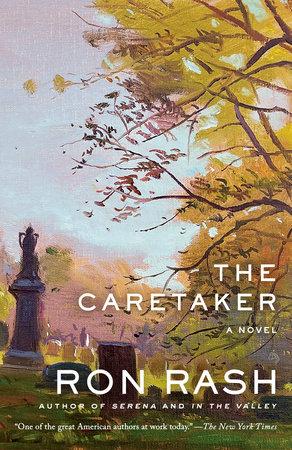

PenguinRon Rash | The Careteker | Penguin Random House | 272 pages | 24 EUR

Ron Rash is probably little known outside the USA. Born in 1953, he is an award-winning author of the classic short story and also writes poetry- neither of which medium is generally ‘exported’. Then there are the novels, which always tell ‘classic’ stories from the dark heart of America. Two were adapted into film, both by lesser-known directors, David Burris (The World Made Straight, 2006) and Susanne Bier (Serena, 2008).

Like his stories, Rash's language and the structures he uses are also ‘classic’. These are texts that could have been written in the middle of the last century. No postmodernism here, nothing experimental - the heart of these texts is always the narrative. This is highly effective, even more so in a novel as dense and elegantly written as The Caretaker, which was published in the USA in 2023 and has been translated into German by Sigrun Arenz with her characteristic subtle rhythm.

Although the novel and Arenz's translation are a delight in their own right with their simple yet purposeful use of language, you may be puzzled at first and wonder what a story about the American countryside during the Korean War can mean to us today? After all, this tale of simple farmers and a merchant family in rural America initially evokes associations with the literature of bygone times - think of Knut Hamsun's great epic, Blessings of the Earth, and Władysław Reymont‘s Farmers. And, of course, Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet.

After all, the story is told against the onimous backdrop of the Korean War. Jacob, who comes from a wealthy, albeit rural family, goes off to join the war, leaving his underage bride Naomi pregnant. Jacob's parents are perplexed, as they have not consented to this marriage. But Jacob's return gives them a second chance. This return of the prodigal son is by turn gripping, sombre, desperate and always surprising. Rash brilliantly exposes the hierarchies of American society, dealing with his subject matter (return, hope, lies and betrayal) in language which is succinct, precise and yet as tender as that of Leonard Frank in his great and similarly themed novella Karl and Anna, which was filmed in 1947 as Desire me with Robert Mitchum and Greer Garson.

In Rash's The Caretaker there is also a proxy for love, Jacob's best friend Blackburn Gant and also, as in Frank’s novel, the dead rise again - unlike in Shakespeare's time, when a tragic ending was mandatory. Reality is paramount in Rash’s novel. Although here, too, parents are put centre stage when they outline their internal smallness, what drives them in life: "It's always been about trying to keep hold of what people wanted to take from us, hasn't it?" "Yes, and that's the reason why life owes us something. Our share of happiness."

This brief dialogue between Jacob's parents about a small life gives us an insight into that life, showing the rift that ran through this rural area in the 1950s, and exists to this day across all of America, indeed most of the world; it explains the war raging on a distant continent- a war that could not be better justified by this morality- and the killing and dreams of the dead experienced by all those who have been drawn into these wars.

Rash lets these voices speak quietly; he explains the big with the small and even reaches something like hope at the end of this dark tale when he shows, as the German philosopher and sociologist Arno Plack once did, in a way that is as astonishing as it is simple, how perhaps the most important thing in life is living without lies.