A future that slips through the fingers

Bloomsbury

BloomsburyAbdulrazak Gurnah | Theft | Bloomsbury | 256 pages | 13,29 GBP

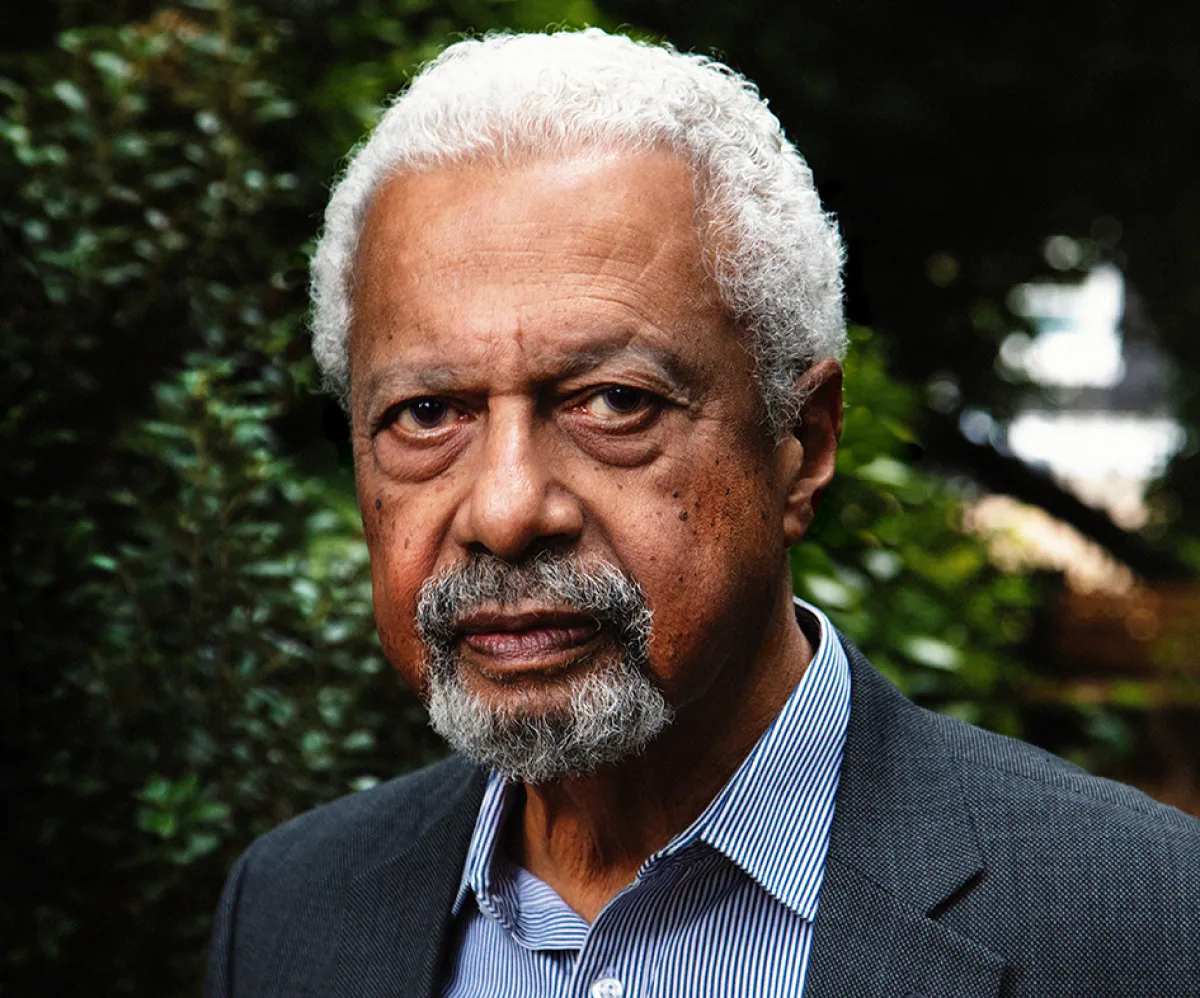

Abdulrazak Gurnah, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2021, is one of those writers whose work never clamours for attention. His novels are characterised by a quiet, laconic power; they insist on slow motion in a age of acceleration. Theft is his first novel since winning the Nobel Prize - and it is a surprisingly unpretentious book, refusing to be labelled as the "great post-Nobel Prize international novel". Instead, it initially seems almost modest, withdrawn, observant. It is precisely in this restraint that its subversive power lies - even if this time Gurnah does not always reach the depth of focus of his earlier works.

The novel is set in present-day Tanzania. There are no colonial flashbacks, no backdrop of historical tragedy, no glimpse at the old world order in the Indian Ocean - all the usual associations with Gurnah are surprisingly absent here. Instead, he focuses on another transformation: the arrival of tourism and capital in Zanzibar, the creative destruction that shakes the social fabric no less radically than once did the colonial rulers. From this perspective, Theft is strikingly reminiscent of Kenyan author David Maillu's great masterpiece Broken Drum. Both novels narrate social transformation not through theory, but through the subtle nuances of daily life - family routines, the things left unsaid and casual cruelties.

The three young protagonists - Karim, Fauzia, Badar - are representative of a generation of Tanzanian cosmopolitans who think, dream and act faster than society changes. Karim returns to Dar es Salaam after his studies, brimming with ideas and liberal promises. Fauzia sees him as both her lover and the key to a life beyond the overprotective confines of her family. And Badar, the poorest and most sensitive of the three, is trying to escape the pull of his own origins. Even here, Gurnah reveals a social hierarchy that no longer bears any resemblance to colonial systems - and yet still carries their long shadows.

Stylistically, Gurnah's novel initially seems maddeningly casual: everyday chatter, small scenes, fragmented dialogue, moments that seem almost superfluous. At first, one wonders whether this prose is not too casual, too calm, too caught up in the mire of insignificant life. But as is so often the case with Gurnah, what appears insignificant is in fact meticulously crafted. Almost erratic leaps in time - a single sentence and three years have passed in the blink of an eye - open up the texture and reveal the fragility of life. The characters age faster than they grow. Opportunities appear and disappear like coastlines in the monsoon rains.

Some of the subplots carry a surprising emotional weight. For example, the story of a woman whose "wishful unhappiness" swings between her child, a well-meaning but over-demanding teacher, and the fear of epileptic seizures. It is in these small abysses that Gurnah repeatedly returns to his previous form; precise, calm and razor-sharp.

In essence, Theft is a novel about social mobility, about the possibility - and the limits - of upward mobility in a country where prosperity and poverty are becoming increasingly entrenched. The question of who is allowed to steal, who is robbed and who owns anything at all becomes an increasingly political issue as the plot progresses. Badar's life in particular - marked by a theft that overwhelms him - shows how social hierarchies resurface, even when the historical framework has changed. Gurnah suggests that modern Tanzanian class strata are not new inventions: they reproduce long-established inequalities, shifting only their visible surface.

The novel gains political depth the closer it gets to the present. The emerging corruption, the hidden violence of economic dependency, the mechanisms of a state that bleeds its youth dry - this is all described by Gurnah if not directly then through the cracks of his narrative. All it takes is a subordinate clause, a glance at the changing working conditions, a roadside comment. And suddenly you understand why the elections in Tanzania at the end of October 2025 were so disastrous - and why, curiously, it was only in Zanzibar that there were no street battles. The novel offers a subtle, almost innocuous explanation: a society that has learned to live with losses does not immediately rebel; it becomes desensitised, pliable, passive and exhausted.

However, as strong as Gurnah's observations are, Theft has moments where the novel feels too light, too cautious, too hesitant. The ending, for example, ripples along almost like a tv series, as if Gurnah was afraid to give his material a clear, sharp conclusion. This may be intentional - the camouflage of lightness, as is common in Latin American narrative traditions. But perhaps here the consistency that Gurnah always possessed in his earlier novels is missing.

Nevertheless, Theft is a clever, quiet and at times paradoxical novel that captivates precisely because of its calmness. It depicts a Tanzania teetering between progress and stagnation, between a tourism boom and moral decay, between old dreams and new inequalities. Gurnah offers no great didactic piece, no thesis nor indictment. But he shows how a society can change without realising it - and how young people try to stay afloat.

And perhaps that is precisely the greatest quality of the author's first post-Nobel Prize novel: the refusal to engage with the narrative obligation of the "great work". Gurnah remains Gurnah - calm, intelligent and alert. He is a writer who is able to convey radical changes with minute gestures. An author who shows that the seemingly incidental is often the most political.

Did you enjoy this text? If so, please support our work by making a one-off donation via PayPal, or by taking out a monthly or annual subscription.

Want to make sure you never miss an article from Literatur.Review again? Sign up for our newsletter here.