The economy of desire and the curse of its fulfilment

Granta

GrantaDeena Mohamed | Your Wish is My Command | Granta | 528 pages | 25 GBP

Making a wish is damned hard! The simpler a wish, the more banal its nature, the less it satisfies the desire on which it is based. And the more powerful its fulfilment, the more inevitably the curse of this fulfilment strikes back. Wishing for infinite wealth, for example, raises the question of what use it is if all that money doesn't bring happiness. But if we were to wish for everlasting happiness, just imagine this cursed scenario: how we, beaming with this very happiness, explain to a grieving and resentful crowd of mourners the infinite joy we experience upon the bitter loss of a loved one. Is permanent happiness even possible, surrounded by unhappy fellow humans in a struggling world? What should we therefore wish for if, like the fairy tales, we have just this one powerful wish? What exactly is this one wish that would cure all ills, promised to us among others by a fish in Grimm's fairy tales, sealed in a lamp in the Arabic tradition of 1001 nights or corked in a bottle of wine. For this is what the Egyptian artist Deena Mohamed tells us in her monumental graphic work "Shubeik Lubeik" with an almost merciless gift for observation.

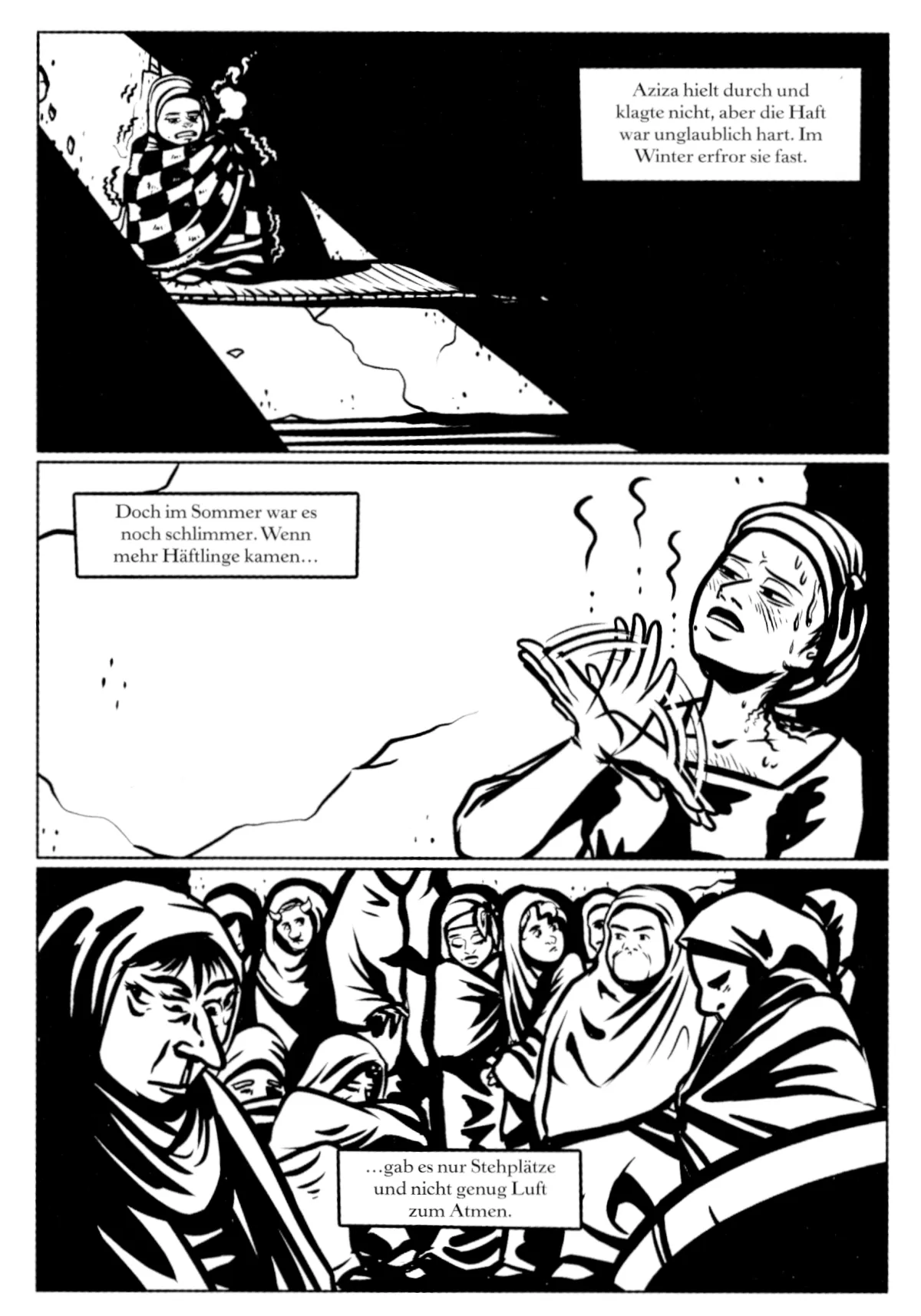

Deena Mohamed systematically structures her epic as a trilogy, each part dedicated to one of the three protagonists: The link in the plot is Shokry. He is the owner of three bottles, each containing a wish, which he received as a reward for excavation work in his younger days. As a devout Muslim, however, he cannot actually do anything with them, as his religion forbids him from trying to control his fate through such idolatry. He therefore wants to sell the wishes to save his small business from bankruptcy. His first customer is Aziza, a poor widow who is mourning the loss of her husband, a good-for-nothing who died in a car accident. After working tirelessly for four years, she has saved up enough money for the wish bottle. The second customer is Nour, a wealthy but lethargic student plagued by a lack of self-esteem, who risks frittering his life away between escapades and therapy sessions. He has no idea what he actually wants from life. And then there is Shokry, the religiously conservative kiosk owner, trying to counter the increasing loss of his modest livelihood with diligence. But he can only look on as his financial situation gradually worsens. Nevertheless, he resists using the third wish bottle as a simple solution to his problems.

This triadic arrangement is not arbitrary in the slightest, but harks back to the magical significance of the number three. It also reflects the hierarchical classification of wish bottles: thus there are third, second and first class wishes, the former being weak and unreliable, the latter almost omnipotent. The central theme, therefore, is precisely this power - not only that of the genie who grants the wish - but more than anything a look at the structures that regulate access to this power. Mohamed creates a system that is bureaucratised to the point of absurdity: a Ministry of Wishes certifies and regulates the bottles, controls their trade and taxes their use. This is a scathing allegory of a state that controls the livelihoods of its citizens but fails to look after their welfare. Through this failure, the state provokes socio-economic desires and then simultaneously controls/regulates their fulfilment. This creates an economy of desires, a reflection of real capitalist economic processes: Desires become commodities whose value depends on their scarcity and potency. In a world that resembles our own down to the most mundane, everyday details, wish fulfilment is real, measurable, classified and, crucially, for sale. Captured in bottles, certified by a state bureaucracy, traded on a market, desire becomes the ultimate commodity and thus a burning lens through which our innermost desires are focused: It is about power, powerlessness, greed, despair, faith. And it is about the inescapable dialectic of creation and destruction that is inevitably inscribed in every fulfilled desire. Are we truly happy when we are without desire? Which life is better: one of unfulfilled longing or one of fulfilled desire?

In spite of all these universally valid basic human questions, "Shubeik Lubeik" is deeply rooted in Egyptian culture. From its depiction of Cairo's various milieus to the detailed representation of social hierarchies, the work is a wealth of cultural specifics: the original Arabic is full of witty language and everyday idioms. This poses immense challenges for translation. The title itself is already a hurdle: "Shubeik Lubeik" is a catchy, rhythmic, meaningful phrase. This formula is particularly well known from oral story-telling tradition involving jinns appearing from a lamp or bottle. As soon as they are released, they often say: "Shubeik lubeik, abdi bayn ideik" "Shubeik Lubeik, your servant is before you." So this is a ritual speech pattern that marks the beginning of the granting of a wish. It represents power over the impossible. A direct German translation such as "Your wish is my command" would destroy both the tonal charm and the folkloristic connotation. Leaving the title untranslated is therefore the most elegant solution, but requires an initial approach from the non-Arabic-speaking audience.

The most obvious and important intertextual frame of reference is the Arabian Nights collection. The motif of the wishing bottle with a genie trapped inside is a cornerstone of this narrative tradition. However, while in the classic stories the wishes are often used to acquire riches, defeat enemies or win love - generally with a more or less happy ending - Mohamed radically inverts the formula. In "Shubeik Lubeik", the wish is not the solution, but the starting point for the actual drama . This gives rise to perhaps the work's most profound philosophical problem: the tyranny of choice. In a world of limited possibilities, wishing is an act of absolute freedom, but once granted, it brings with it an almost unbearable responsibility. Every wish is a decision with incalculable consequences, an ethical abyss into which the characters are plunged. Should one wish selfishly or altruistically? Express a material or a spiritual wish? The impossibility of formulating the "perfect" wish without triggering unintended side-effects exposes human desire itself as imperfect and dangerous. This is where Mohamed's greatest strength lies: she does not simply deconstruct the fairy tale motif, but dissects it philosophically and ironically. Where Scheherazade saves her own and others lives by telling stories, thus celebrating narrative art, Mohamed shows the limits of the narratability of happiness. Her characters often fail to shape their desires into a coherent, harmless formula. The genie is not a servant spirit, but an impersonal, almost natural force whose logic remains inscrutable. It is no longer a question of the miracle as a healing force, but of its commodification and control in a modern, disenchanted world.

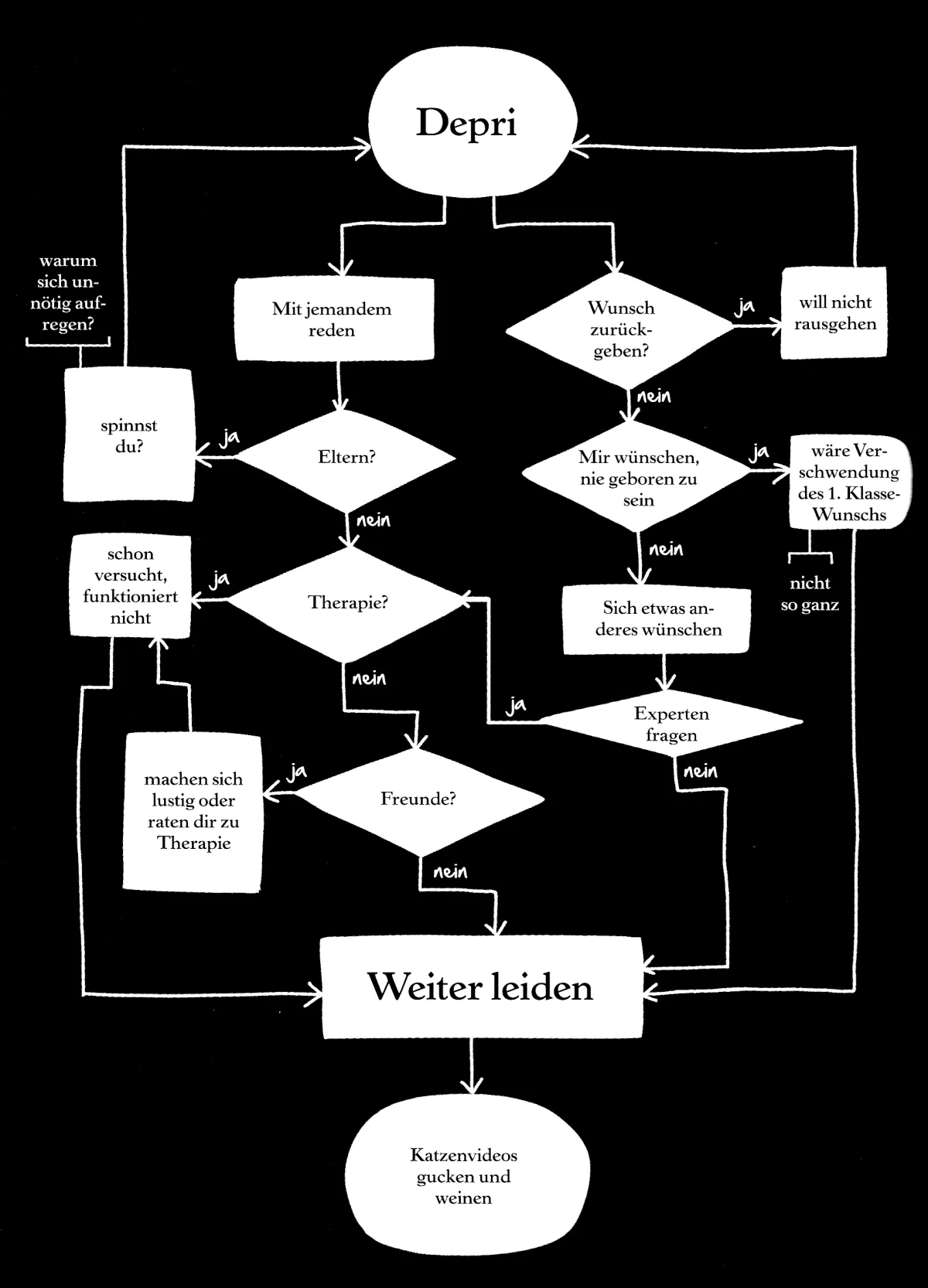

The narrative is by no means linear. Mohamed employs a complex, often non-chronological, montage technique that cleverly interweaves flashbacks, dream sequences and factual inserts such as tables or diagrams into the plot. This is also evident in the visual representation of the wishes themselves, more calligraphic streams of energy than emanating genies. Once expressed, the wish unfolds its power. Mohamed's style is thus a successful synthesis of traditional Arabic visual forms and the dynamic language of modern comics. The lines are clear and the character drawings cartoon-like, but become expressive and abstract in the metaphysical moments of wish fulfilment. Particularly notable is the use of text and typography. Arabic calligraphy and ornamental patterns flow seamlessly across the panels, with Mohamed artfully varying the reading direction depending on the context. The graphic novel is read from back to front and from right to left in the traditional Arabic style, or from left to right for the interspersed factual depictions and explanatory patterns.

Deena Mohamed, born in Egypt in 1995, is an Egyptian illustrator, graphic designer and author. She first became known with "Qahera", a webcomic she started at the age of 18 which, with a Muslim superheroine who fights Islamophobia and sexism, deals with social issues in satirical form. The work went viral and she became a household name on the comic scene. In 2017, she self-published the first part of "Shubeik Lubeik" and promptly won the Grand Prize and Best Graphic Novel at the Cairo Comix Festival. Subsequently, Dar al Mahrousa took over publication in Egypt from 2018/2019/2021. In 2023, the complete English edition was published in the USA. Mohamed is also involved in civil society groups (e.g. Harassmap) in the field of Egyptian women's rights. Her approach is thus deeply rooted in Egyptian culture, yet critically reflects it in a stylistically confident blend of magical realism and everyday urban satire.

This balance is ultimately reflected in "Shubeik Lubeik"'s refusal to provide a simple answer. The comic forces the reader to ask themselves: What would I want? Deena Mohamed acknowledges the agonising impossibility of finding a satisfactory answer. By embedding wish fulfilment in the everyday lives of ordinary and marginalised people, she politicises the question of happiness. It is no longer a matter of abstract metaphysics, but also about the question of the (im)possibility of concrete liberation from inner constraints, poverty and injustice. But is such a utopian state possible and even desirable in this world? Or are we all, in the end, just fools; donkeys who wished for human form?

Did you enjoy this text? If so, please support our work by making a one-off donation via PayPal, or by taking out a monthly or annual subscription.

Want to make sure you never miss an article from Literatur.Review again? Sign up for our newsletter here.