The significant inability to decide between fried eggs or scrambled

Scholastic

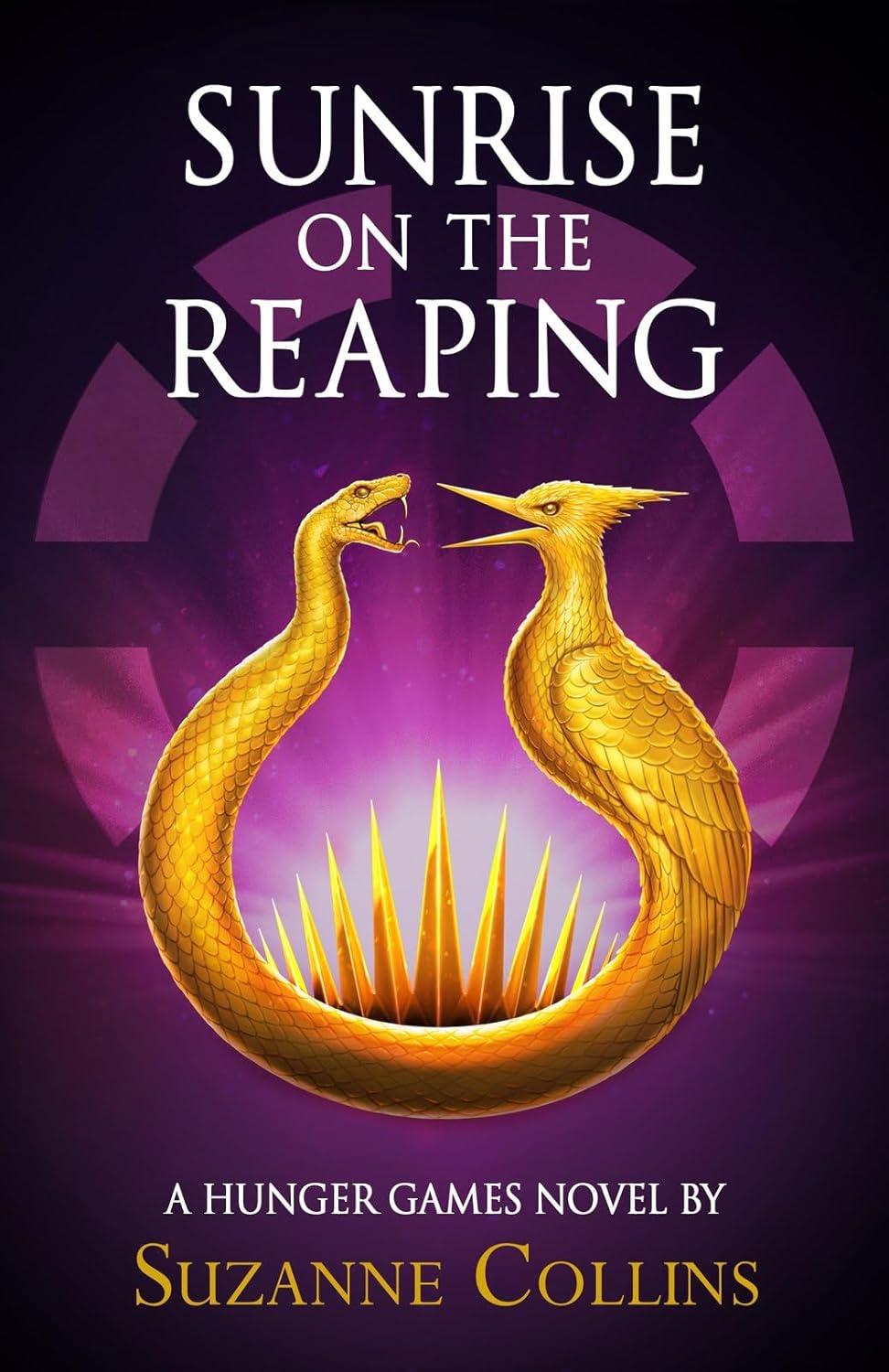

ScholasticSuzanne Collins | Sunrise on the Reaping - Part 5 of the Hunger Games series | Scholastic | 382 Seiten | 19,99 EUR

Those who have read Suzanne Collins' Hunger Games novels, which have won numerous awards since 2008, may naturally wonder whether the fifth novel, Sunrise on the Reaping, was even necessary. After all, Collins is essentially telling a story that she has already told in previous books. In particular, the passages in which the teenage protagonists kill each other in a hypermodern version of the Roman Colosseum in order to satisfy the bitter morals of the autocratic central government, which wants to remind us of the devastating civil war in the past, feel almost too familiar.

But this is not solely due to the first three novels, in which the teenage Katniss Everdeen empowers herself and questions the authority of the Capitol, the central government of a dystopian USA. And of course, Collins doesn't only reference the ancient past, which is familiar to many readers: according to the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur, the ancient Greeks sent seven boys and seven girls from Greece to Crete as a gift. Perhaps this is due to the film adaptations, which have been even more successful than the novels and are certainly more exciting cinematically than the simple language with which Collins writes - their visual language has a very lasting effect. The main reason, however, is probably the success of new formats such as the South Korean TV series Squid Game, in which people kill each other one by one in an arena in the hope that at least one of them, through victory, can give their precarious life a new future. Or the waves of extremely successful dark romance bestsellers in New Adult literature, in which young girls in particular are exposed to moral grey areas and in which violence and oppression are often at the heart of the plot without being questioned.

Although violence does also play a central role in Collins' work, here it is politically motivated, unlike in the aforementioned formats. This has been the case from the very beginning of the series, and it was no coincidence that Collins' literary breakthrough came at a time when autocracies and populism were beginning their global march of triumph. Collins also explicitly comments on her latest volume that she was influenced by David Hume and his ideas. These show a humanity in which the few repeatedly rule over the many. How topical these ideas are is illustrated not only by the worldwide triumph of autocratic and dictatorial systems over democracies, but also by the way in which these systems come to power: It is often young voters for whom freedom is too demanding and who want "strong" leadership. This is as true in the Philippines as it is in the USA, Germany or Argentina.

Collins' Hunger Games series makes abundantly clear where this electoral behaviour leads and what it feels like to no longer be free. The importance of demonstrating this is illustrated by a comparable development after the Second World War. As long as contemporary witnesses were still alive and able to speak about what it meant to be led into war and genocide by a dictatorship like that of the Third Reich, their testimony also seemed to provide a shield against the coming catastrophe. But with the passing of the last contemporary witnesses, this spell seems to have been broken.

While literature cannot completely replace this testimony, it can help us recognise the mechanisms and arm ourselves politically. Collins takes a very "cinematic" approach in the fourth volume (The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes, 2020) and also now in the fifth. She uses the prequel technique - telling a story that precedes the main story of the first three volumes, in which the charismatic Katniss comes into her own. In The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes, Collins reached back 50 years to show how the originally sympathetic character of Coriolanus Snow becomes the tyrant we come to know in the first three volumes. This was a classic dictator-coming-of-age story, showing not only that everyone is ultimately corruptible, but also that any democracy is vulnerable to that corruptibility.

In Sunrise on the Reaping, Collins now goes back 24 years. Whereas in the first prequel she describes the coming-of-age of the "authority", in Sunrise on the Reaping she focuses on the coming-of-age of the "victims", the ruled. But quite different from Katniss in the first three volumes is Haymitch Abernathy, the "advisor" who stands by her side in the arena 24 years later. He is a broken hero, someone wracked with self doubt, not even sure whether he has the ability to decide between a scrambled and a fried egg.

But Collins shows that it is precisely this doubt that makes people resilient and enables them to resist the temptation of power. It is this tolerance for ambiguity that enables us to remain open and therefore democratic. Turning the classic "loser" into a hero is nothing new in New Adult and children's literature, but Collins manages to weave together elements of political thinking and action so convincingly that it is a real joy to read.

Although "joy" is of course the wrong word, it does rather show me that hope for an end to the current trend is still alive. And all the more so as more than 1.5 million copies of the novel, published simultaneously worldwide in mid-March 2025, sold in the first week alone, including 1.2 million in the USA - one of the countries currently most committed to the autocratic path. That's double the number of copies sold of the first prequel on its release and three times as many of the third volume in the series, Mockingjay, published in 2010. Collins' message is likely to be amplified once again with the film adaptation, due to begin shooting in July 2025. The novel could therefore not only point the way forward for future first-time voters, but also stand as an important bulwark against the apolitical tendencies of contemporary young adult literature.