Rain mixed with snowflakes

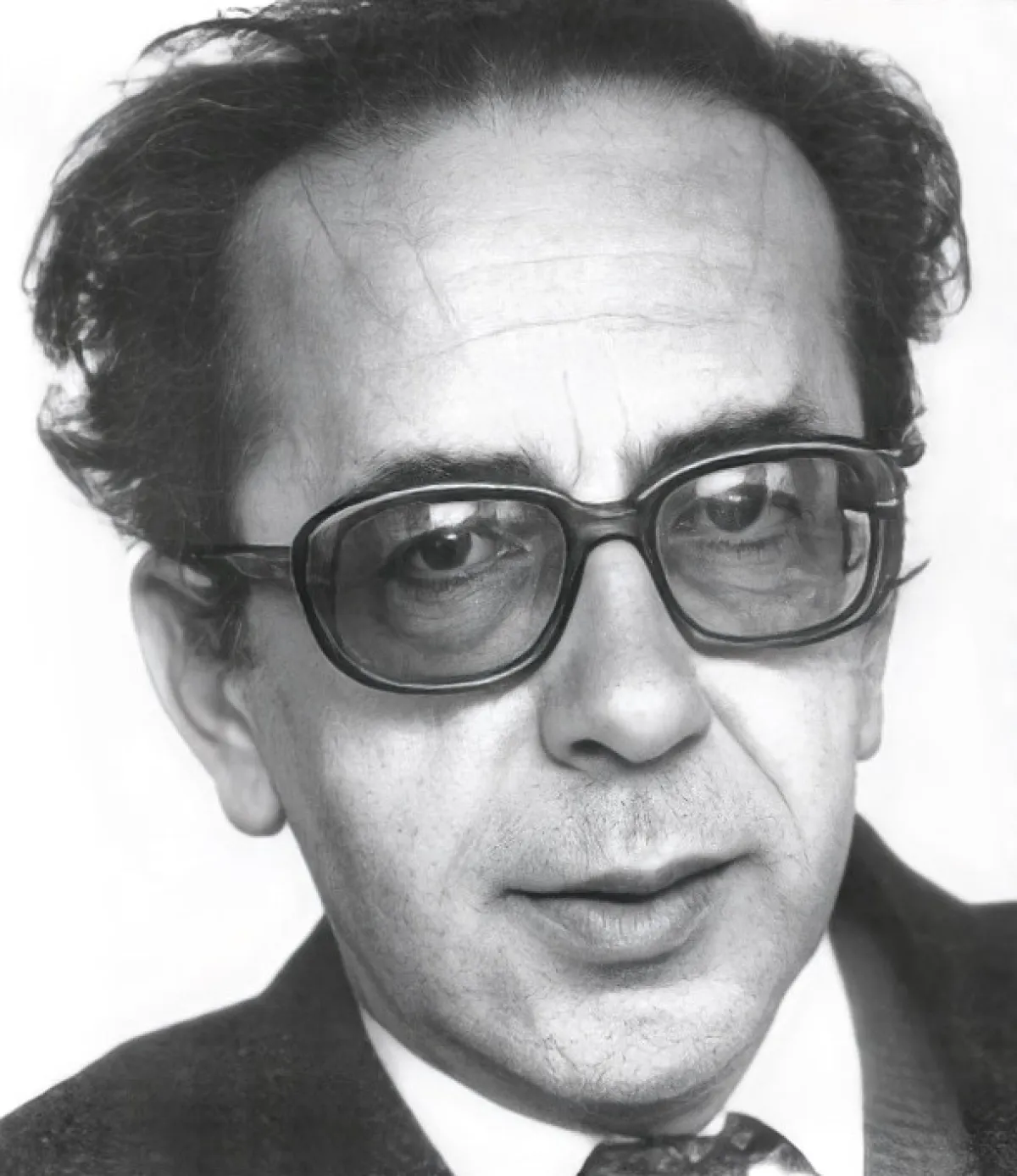

Ismail Kadare [ismaˈil kadaˈɾɛ], born on January 28, 1936 in Gjirokastra; died on July 1, 2024 in Tirana, was an Albanian writer.

The greatest authors usually come into our lives when we least expect it. This has happened to me not only with Albert Ehrenstein or Naguib Mahfouz (and many others), but also Ismael Kadare, whom I discovered in the bookshop "Das Gute Buch" in Halle. Back then, in the late 1980s, the GDR still existed and anyone visiting from the West had to make a compulsory daily exchange of 25 Deutschmarks, for which they received 25 East Marks. As books cost much less in the GDR than in West Germany, using this compulsory exchange to buy books was an ideal investment, especially since the GDR book market was so full of surprises.

This is how I came across my first book by Ismael Kadare, the collection of stories The Caravan of Veils, the first sentence of which, like almost all the first sentences of Kadare's stories and novels, immediately captivated me: "Never had Hadji Milet been wished 'bon voyage' at the start of a trip as often as those days early in September, when he was about to set off for the Balkans."

In this short story, Kadare gives an flawless account of a past that seems far away. With his crystalline, scalpel-like language, he opens up a densely composed past in order to speak of the present. A present that, like the past, has been plagued by the scourge of a totalitarian regime. In The Caravan of Veils, it is the Ottoman Empire that destroys lives with its arbitrary, completely unpredictable decisions. Kadare dissects this past so precisely with his language and historical accuracy that the blood oozing out runs cold and the past remains the past. At least for the censors of totalitarian Albania, ruled by Enver Hoxha. Likewise for the censorship of the GDR, which is why I was naturally surprised to have discovered this book here - on either side of the divide, Kadare's stories could always be read as a subtle commentary on life in a dictatorship and on survival as an artist.

Unlike in Bridge over the Drina by Ivo Andric, Kadare's Ottoman Empire in The Caravan of Veils or his Palace of Dreams (1981) was not an experiment in how a multi-ethnic state could function and thus a model for a functioning Yugoslavia, but rather a transgenerational trauma carried through the terror of the Ottoman Empire to the present day of an Albania that, through Hoxha, now exhibits not only paranoid but also self-destructive traits.

Today, it is difficult to understand why Kadare, although nominated several times, did not receive the Nobel Prize like Andrić . Perhaps he was simply too "political", too "European". In his criticism of totalitarian systems, Kadare is very similar to the equally highly political and very European Manès Sperber and his still salient novel Like a Tear in the Ocean, . This is also evident in earlier works such as The General of the Dead Army (1963), in which Kadare, like Sperber, visits the fields of the dead of the Second World War in order to fight against an unreconstructed present. The magnificent opening sentence encompasses almost everything we will later learn: "Rain, mixed with snowflakes, fell on the foreign soil."

In 1990, when Hoxha's time was over but democracy continued to be held hostage under the Albanian transitional ruler Ramiz Alia, Kadare also opted for "foreign soil" and exile in France. He continued to write against the forgetting of a totalitarian past and in The Successor (2006), he again brings to life, with sombre images, the workings of a totalitarian state. Perhaps because Kadare was at pains to silence critics who accused him of having indulged Hoxha's system too much, even of having been a favourite of the former Albanian leader, this novel is more desperate, even fatalistic, than his previous novels.

However, as someone who had been "affected" for decades, Kadare may simply have realised that history was threatening to repeat itself, as once again autocracies and dictatorships were becoming commonplace and acceptable. Yet another reason why Kadare, who died in Tirana on July 1, 2024 at the age of 88, should be read again and again.