The last of their kind

It’s summer in the global south (which is winter in the global north), and for the month of January Literatur.Review is bringing them all together, publishing previously untranslated or unpublished stories from the north and south of our world.

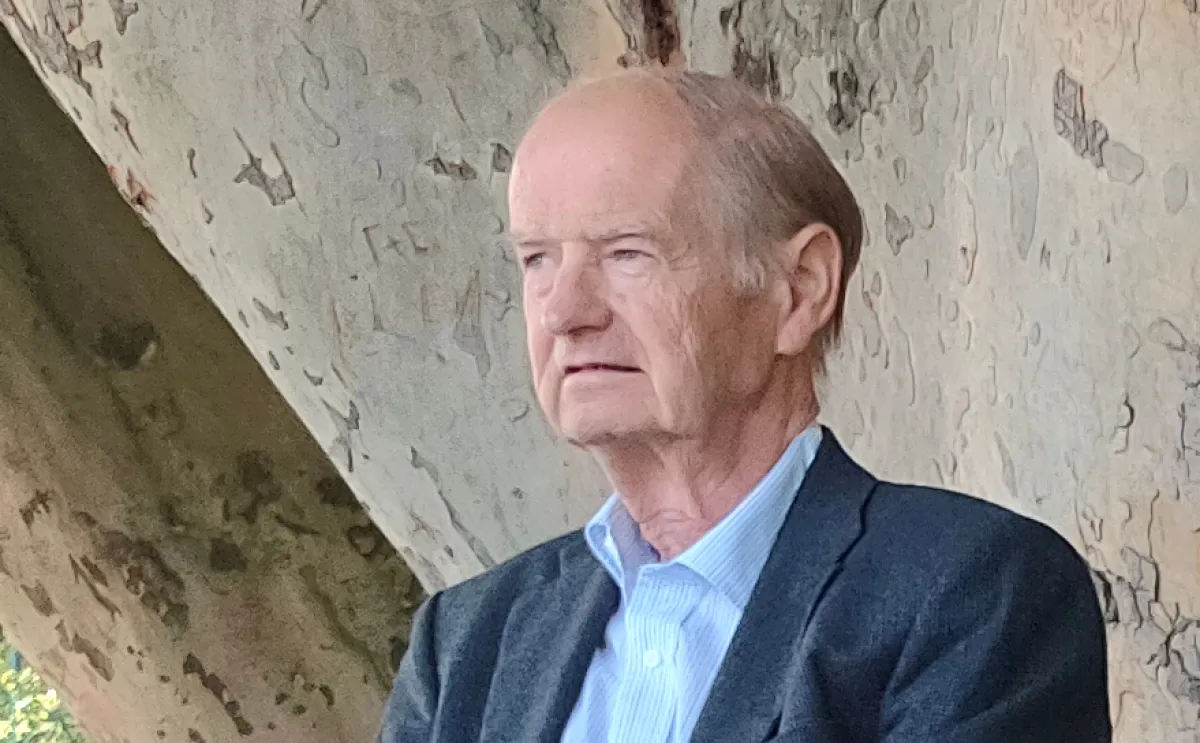

Fritz Freithoff is a German-language author, translator and photographer from Namibia. He grew up on a farm near Windhoek and later migrated with his parents back to Hanover (Germany), from where his grandfather had left for what was then German South West Africa in 1885. Since then, he has commuted regularly between Hanover and Lüderitz with occasional detours to Cape Town, where he ran an antiquarian bookshop with Julien Adler and published the Authentic Africana Series.

Whenever I saw my sister's children, I never thought anything kind about them, because for longer than these children have existed, I have had bad memories of their father, about whom I have always spoken with contempt, even anger.

It all started when Andreas wanted to marry my sister, when she was going through her first serious crisis. Having failed to fulfil her great dream of becoming a violin maker - she was a girl, and women stood no chance in this field - she had decided to do an apprenticeship as a florist; if she couldn't use her ear, she at least wanted to use her eye. When she told me about this at the time, I didn't understand either of these aspirations. My sister wasn't particularly musical - apart from the recorder at Christmas, she had never played an instrument - nor was she a person who spent time enjoying the beauty of nature. But she was determined and persevered with her training, even though the work was poorly paid and the customers rarely left the small store where she was employed in a friendly manner.

Her love life wasn't much better, always just short, fairly joyless and painful interludes. But then one day Andreas came into the shop and invited my sister to dinner. Why not, my sister thought. Her apprenticeship was almost over and seemed to have gone well - maybe things would start looking up with men too. Over dinner, Andreas told her that he had just finished his military service and was now going to work for the railways in his dream job. Oh, dream jobs, sighed my sister. Yes, dream jobs, Andreas confirmed, ignoring her sigh and telling her how difficult following his own dream had been. He told her the whole story, a long story that wasn't as simple as it might sound: it must have been, he recalled, the year Top Gun had come out, his one favourite film. It was the year before his A-levels. Everything was fine, he had little need to study, and in any case it was only a stopgap, as he had actually already applied for a job at the railroad after the 10th grade, after his secondary school leaving certificate. But due to a recruitment freeze, he had not been accepted. He had been annoyed about this for weeks, as railways had always been more than just a job for him. He had been collecting model trains since he was a little boy, from all countries, in all sizes, and would play with them in his parents' cellar. But one morning, that Top Gun year, he had turned on the radio at breakfast, and couldn't believe his ears when he heard on a business program that the railways were recruiting again. In almost all areas. He wrote his application that same afternoon, without consulting his parents. They were completely flabbergasted when ,two weeks later, instead of going to school he went to a job interview at the railway headquarters at the main station. However, they didn't try to dissuade him, not even when he was accepted and decided to drop out of school before doing his A-levels. He started training as a signalman, his dream job, in which he would now earn his money working shifts after leaving the army. My sister sighed again and said with longing: "Fine."

They got married quickly, just a few months after this conversation. I was invited to their wedding and was delighted that I would be back in time from a long field trip to the Kenyan-Ugandan border with Esther and her children. But my joy evaporated when I saw Andreas walking down the aisle in his army uniform. I asked my parents, who were sitting next to me, why he was doing this. It was a good deal, they replied. In return, he was getting a tidy sum, which he and my sister could use to cover almost the entire cost of the wedding. However, this pragmatic reason only increased my horror and was to shape my view of my sister's life for decades to come. I could no longer see what she became, only what she was. Or perhaps a better way of putting it would be: I saw everything she and Andreas did through the dull fibres of a grey Bundeswehr uniform.

The first time I entered their apartment, my sister proudly showed me around. Each room had been painted in a different pastel shade; they had bought all the furniture from Ikea. It was a bright, youthful apartment. In the bedroom, my sister had arranged at the foot of the bed, the knitted cuddly toys that our mother had given her during her childhood; mostly hippos, because my sister loved hippos more than anything. We had never had anything to do with hippos during our childhood in Namibia. We lived on the coast and our parents weren't interested in anything as touristy as visiting a national park.

Over the years, other animals were added, but still mostly hippos. Years later, when they already had three children within the space of five years and had moved to a larger apartment, I was shocked to discover that Mara and Andreas' entire bedroom was now full of cuddly toys. On shelves, at the head of the bed, but also on the opposite wall, shelves had been installed on which sat nothing but cuddly toys of all sizes. I wasn't so much shocked by the bizarre sight as by the idea of Andreas and my sister having sex in this environment. And yet they had had three children! But the idea troubled me and I kept my visits short, avoiding looking into the bedroom as much as I could.

It wasn't only the collection of cuddly toys in the bedroom that kept me away; I could hardly stand my sister's monologues about parenting. As soon as I'd arrive, we would take the children for a walk, usually to a nearby playground. Once we were sitting on a bench and the children were playing, she would start talking about other parents who didn't know how to bring up their children, or children who were unhappy because they lacked the heart of a family or because their parents didn't care. This went on all the time. She talked incessantly about her superior parenting model, which consisted solely protecting the family - as if from Indians in the Wild West - eating dinner at five o'clock and never drinking alcohol in front of the children except in exceptional circumstances.

As my sister and her dogmatism became increasingly alien to me, my perception of Andreas started to change. Although I still couldn't get the Bundeswehr uniform out of my head, I began to respect Andreas for his professional passion. That may sound a little stiff, but, on reflection, respect is actually the right word to describe the impressive symbiosis between professional and private life that Andreas had now achieved.

No matter what happened - his son being brought home by the police for drunken behaviour, his younger daughter not being accepted into the police because of a judo accident and his older daughter having a bodybuilder as a boyfriend - all of this rolled off Andreas' back. . While my sister was constantly getting upset about these failures in her educational plan, especially when her son enlisted in the German army but left after a year and the training he had completed as an aeronautical engineer was not recognised, plunging him into depression, Andreas seemed to observe these vagaries of life as if he were sitting in his signal box and only had to trigger a few signal commands to get the train of life back on track.

And somehow, everything always worked out. His son was taken on by MTU, an engine manufacturer, and he was so happy there that his younger daughter gave up her dream of becoming a policewoman and started training at MTU too. And his eldest daughter struck lucky with her bodybuilder, who now held an important position in a furniture store and married her in a big, glittering wedding to which I was not invited.

Although this exclusion hurt me, I was happy for Andreas. After all, the course had been set correctly and I think today - although I didn't then - that it wasn't just down to my sister being such a strict parent, that the trains had picked up speed again, but that both of them had played their part. This change of perspective cost me a lot of energy. Because it meant nothing less than banishing the army uniform from my mind and instead recognising Andreas for who he was, someone whose blind confidence and calm composure, with which he had fulfilled his professional dream, had enabled him to become a role model for his children.

This desire to correct my thinking (and my writing) arose during my last visit to my sister, which, as always, was not supposed to last longer than an hour; that was all I could stand before becoming inwardly enraged, a state I would find difficult to conceal from Mara and meant I risked offending her with my outbursts. After half an hour, I closed myself off as usual and didn't ask any more questions or say anything. During my previous visit, I had let my anger get the better of me. I had told Mara about a trip to our childhood home, to David in Windhoek, with whom we had often played as children because he lived on the neighbouring farm with his parents, who were friends of our parents. We would occasionally sleep over at eachother's houses so that the parents could go to the few festivities that took place in the German district of Lüderitz. Exasperated by the narrowness and strictness of my sister's home, I had emphasised the spontaneity, the completely unpredictable, childfree chaos of David's house, extending to his car, which resembled a rolling trash can. Because I knew that my sister remembered David, perhaps even had a childlike love for him in the past, I also pointed out David's extremely spontaneous career changes, which took place every three years. I talked about David's mother, whom my sister only vaguely remembered, and about the freedom she had always allowed her son, whatever he did, to the point that mother and son became more like friends. However, David's best moment with his mother came late in life - and I told my sister this in great detail - when his mother invited him to go to Mariental with her friends a few years ago. The rains had fallen that year on the red and yellow desert more heavily than at any other time since their family had been living in Namibia. And when the rain fell, David's mother and her friends, who were now all around 70 years old, set off for the nearby Mariental, because they knew that the morning after the rains, the most beautiful flowers would bloom there, more beautiful than anywhere else in the country. She had probably taken him with her because he was going through another one of his difficult periods, but also because he had never experienced this fleeting desert spring before. They spent the night on blankets in the open air and when David woke up with his mother and her friends, he was surrounded by a sea of flowers, a beauty from which he would never recover. I didn't tell my sister about his suicide shortly after my visit, the gun and the blood splatters that would still be visible on the ceiling of his room months later. And I also kept quiet about my grief, because I still don't know why the suicide rate among the few remaining German settlers in Namibia is so high, even for those who don't rely on the typical concept of 'home' and who had alternative homes, like the writer Giselher Hoffmann in Berlin, but who were nevertheless dragged down by this uncontrollable maelstrom. Perhaps I kept quiet because I was afraid of being the next one to press a rifle to my head. But certainly because I wanted to unsettle my sister and divert her from her straightforward path.

My sister didn't comment on this very different life, but immediately launched into a story about her own life in a way that, as always, resembled a press release and made it clear to me that David's story had definitely had an impact.

A year after that visit, however, she sounded the same when she told me that her work at the taekwondo studio was getting more and more attention, even being mentioned in the regional newspapers. Although there were still mixed groups with a high proportion of boys trained by the founders of the studio, whose parents migrated to Germany from Turkey 50 years ago, her girls' classes were the ones with the greatest potential for growth. Excited, her cheeks red, my sister told me that it has become much more dangerous for girls now in Germany, because each new wave of immigrants was bringing people from cultures who might misinterpret the public appearance of young girls. Basic training in self-defence, she concluded, should actually be mandatory for our girls. But there is also another group, my sister added, who are almost more important. Traumatized girls, girls who were victims of abuse and who could reconnect to a healthy, holistic life through their training. I had to laugh. That couldn't fit better in these times! What do you mean? My sister looked irritated and I wondered if I should explain it to her, she who hardly read the newspapers. I told her about Harvey Weinstein, about Me-Too and all this nonsense about supposed migrant waves. My sister nodded and then launched into another monologue, explaining that the Weinstein women were certainly not the same as the traumatised girls that she worked with; that they had only suffered 'light' abuse, so to speak, and in fact it had probably helped their careers. I felt the old anxiety and a quiet anger rising in me and broke off the conversation by telling her that I would like to speak to Andreas, who was working on his trains over in the former children's room.

I marvelled at the many transparent plastic boxes that were neatly stacked and covered a large part of the room; at the back was the large panel on which the model railroad was set up and where Andreas was standing, screwing something on. I ran my hand over the boxes like ears of wheat in a field. These are all models that once existed? All actual trains? Andreas looked up and smiled at me. Oh yes, models from over forty years ago. I bought my first train set when I was 13 years old. From then on, there was really nothing else for me, not even professionally, as you know. Just like Joseph Conrad's hero in his novel Lord Jim, I thought, who followed his dream to its conclusion, although Andreas's dream was pure, with neither guilt nor tragedy. He looked down at the tracks again and continued his work, immersed in his game, a game which had become serious during his shifts, which he wouldn't have had to do any more if he had accepted one of the many offers of promotion and gone into administration.

When he had finished, he set one of the trains off and the smile that crossed his face as the train started to move was the same as the smile on my sister's face, who'd joined us and was standing in the doorway. I suddenly understood what the two of them had in common. I thought of Tom Cruise and his Top Gun sequel Maverick, which had been in cinemas more than thirty years later. Cruise brought that same smile to his role; Pete Mitchell had never been promoted either, but maintained and flew his airplanes the way Andreas conducted his railroads, at home as well as in his professional life.

For my sister, Andreas is an old-school fighter pilot and for him, my sister, who has always defended her children against all of life's adversities and now does the same with young girls, is also an old-school fighter. But why did I think of the expression 'old school' at that moment and write it down like that? Because they belong to a dying species, they are like the old miners in the pits of the German Ruhr and in the north of England, for whom the job, however hard it might have been, was never just a job, but always their whole life.