Between ancestral memory and the digital future

Yolanda Arroyo Pizarro (Guaynabo, Puerto Rico, 1970), Afro-Caribbean and Afro-Lesbian, is a professor and award-winning writer. She has published books promoting the debate on Afro-identity and sex diversity. She is director of the Department of Afro-Puerto Rican Studies, a performative creative writing project based at the Ashford House Museum in San Juan, Puerto Rico. She is also founder and director of the Cátedra de Mujeres Negras Ancestrales, a response to UNESCO's call to celebrate the International Decade for People of African Descent. In 2015 she was invited by the UN to speak about women, slavery and creativity as part of the "Remembering Enslavement" program. Her short story collection 'las Negras', winner of the 2013 National Short Story Award from the PEN Club of Puerto Rico, explores the limits of the development of female characters who challenge hierarchies of power. 'Caparazones', 'Lesbofilias' and 'Violeta' are among her works exploring transgression from an openly lesbian perspective. She has also won the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture Award, in 2012 and 2015, and the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture National Award in 2008. Her work has been translated into French, German, Hungarian, Italian and Portuguese.

"Literature is still a trench. In the digital, it also becomes a living archive, a performative act, a possibility of instantaneous replication". - Yolanda Arroyo Pizarro

(1) The lowercase writing of the given article, in the title of the book, highlights the capitalized writing of Negras, thus conferring a clear narrative agency to the women protagonists of the various stories

In an age where algorithms shape our realities and social networks redefine forms of resistance, a fundamental question arises: How can voices of African descent participate in, and even lead, the transformation of the digital space? The answer lies in the work and activism of Yolanda Arroyo Pizarro (1970), a Puerto Rican writer who has managed to build extraordinary bridges between ancestral memory and the emancipatory potential of digital technologies.

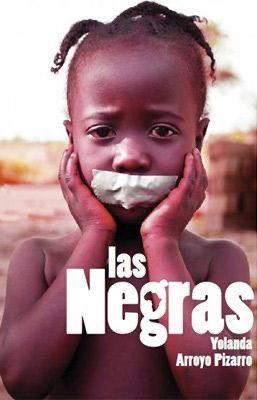

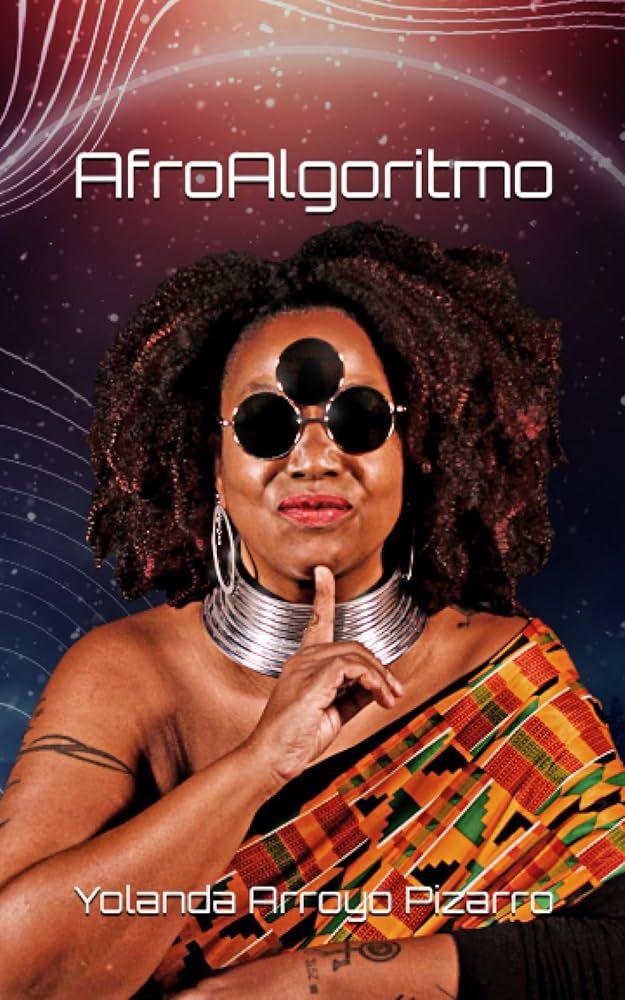

Arroyo Pizarro is not only a storyteller; she is an architect of possible futures, a hacker of dominant narratives, a cyberactivist who weaves resistances from the Caribbean to the world. In this article, we will examine her works las Negras(1) (2013) and Afroalgoritmo (2023), and her activism.

In las Negras, the author recounts the stories of enslaved women, told to her in part by her grandmother Petronila. The work has been republished several times, translated into English and is one of the contemporary references in Latin America on black feminism and anti-racism. Afroalgoritmo is a collection of texts that explores the plurality of black bodies, attempts to break algorithmic determination and articulates narratives where ancestral memory connects with worthy future projections.

(2) The concept of Afrociberactivism has been presented by the Gabonese researcher, resident in Senegal, Odome Angone, in various spaces, academic and personal.

The work of Yolanda Arroyo Pizarro, particularly the dialogue between her two books las Negras (2013) and Afroalgoritmo (2023), constitutes a unique laboratory for understanding how contemporary Afro-Caribbean literature functions as an early form of Afro-cyberactivism. This concept, defined by Odome Angone as "the set of practices, movements and dissident discourses 2.0, mostly gestated, in a decolonial and intersectional key, from social networks to give voice and identity to Afro collectives immersed in multiple oppressions of a systemic nature"(2), finds in Yolanda Arroyo Pizarro one of its most sophisticated manifestations. Her work combines narrative strategies that connect directly with contemporary forms of Afro-centred digital resistance: making visible and confronting forgotten or untold stories, the construction of transnational networks through the strategic use of multilingualism, and the documentation of testimonies with a narrative agency. Thus understood, Afro-cyberactivism allows us to examine how Afro-Caribbean literature, through its connection to cyberactivist practices, expands the scope of literary resistance in the digital era, becoming a fundamental tool for the reconfiguration of identity and the struggle against contemporary forms of racism and exclusion.

libros 787

libros 787las Negras | Yolanda Arroyo Pizarro | Books 787 | 150 pages | 18.95 USD

The work of Yolanda Arroyo Pizarro shows us that literature can not only anticipate contemporary forms of digital activism, but can also serve as a laboratory for developing more complex strategies for social transformation. Her work reminds us that the future is not something that happens to us, but something we can write, change and transform through our resistant heritage. To better understand these dynamics, we talked with the author about her trajectory, her experiences as an Afro-Caribbean migrant woman and her vision of literature as a dissident technology.

María Ignacia Schulz: Ten years have passed between las Negras (2013) and Afroalgoritmo (2023). Could you tell us what this process has been like and what led you to become interested in the digital world revealed in the title of the second work?

Yolanda Arroyo Pizarro: That transit has been, in many ways, an evolution and an insurrection. 'las Negras' was born out of a visceral desire to reclaim our ancestral memories, to tell the stories of enslaved black women from the standpoint of their dignity and agency. 'Afroalgoritmo', on the other hand, proposes a leap in time: it is my attempt to question what Afrofeminist struggles will look like in the future, in a dystopian Caribbean shaped by artificial intelligence, data control and reconfigured colonial surveillance.

My interest in the digital is neither recent nor superficial: my curriculum vitae indicates that I have been a specialist in educational technology since 1999. I am one of the first graduates of the Microsoft Office Academy in Puerto Rico and was part of the team that trained almost 4,000 teachers on the island in the use of the Office Suite. That early relationship with technology gave me tools, but also a critical eye. Today I explore how those algorithms, sold to us as neutral, reproduce colonial and racial biases. I write Afrodiasporic science fiction in order to claim that imaginative territory as our own.

How does your experience as an Afro-Caribbean woman in migratory contexts inform the narratives of resistance in your works?

Migrating as a Black woman is not the same as simply migrating. There is a hypervisibility of our bodies, a constant suspicion, an emotional surveillance that is placed on us. Each of my texts bears the mark of those journeys. Whether I am writing about enslaved Maroon slave women in the 18th century or black cyborgs in the 2300s, I am always writing from a migrant consciousness: the displaced body, language as a border, the desire to build home where we were told we didn't belong.

On the day of the Madrid launch of the book Mientras dormías, cantabas, just as it was starting, two xenophobic Spaniards threw stones at the author of Penguin's Yeguas de Troya imprint, and at the immigrant women with us, along with Gabriela Wiener. "Why don't you leave?" they said. "Calm down, it's normal," they consoled us. That incident made me think of two other recent events: First, a fellow writer from Mexico shared with us in Madrid that the entrance code for her hotel during the Book Fair was "1492." A number that, for many, does not represent a welcome but an open wound. Second, while I was trying to take a cab dressed in my Afro-centred clothes and a turban, the cab driver told me that he almost did not let me get in because of "my turban and my clothes". As I got out, he asked me what religion I was and warned me that it could affect my Uber score. Days later, sure enough, my user profile was affected. This is no coincidence. It is everyday racism, it is persistent coloniality, it is ongoing symbolic and real violence.

But this alienation does not only happen abroad. In my own country, Puerto Rico, some do not see me as Puerto Rican. When they see me, they speak to me in English, as if I were not from here, or they ask me where I was born. I am "something else," both regionally and sexually. I don't fit into the official narrative of Puerto Rican identity: too black, too lesbian, too much of a protestor. This imposed otherness also migrates with me, it makes me a foreigner even in my own land.

We continue denouncing, writing, claiming, even if it hurts. We continue to resist, even if they throw stones at us. In my story "Wanwe", for example, the protagonist migrates involuntarily. Her forced journey to another territory and to the future, to another dimension and another place, is an expanded metaphor of our multiple real migrations, those of the body and those of the spirit. She carries, like so many of us, a story that she did not ask for but one that changes her. In that story, as in my life, writing appears as a vehicle of resistance.

You are a writer who is also present in the digital world, and from there you practice resistance, as with your literary work. How do you build the bridge between the literary and the digital?

My activism is not separated from my literature. On social media, in campaigns such as #PeloBueno, #SaladeLecturaAntirracista, #CelestinaCordero and #EnnegreceTuProntuario, I have woven spaces of community pedagogy, living memory and counter-narrative. Poetry and cyberactivism merge when I share microverses that denounce, when I document Afrofuturist performances, when I promote Afroqueer justice campaigns. These bridges are built by writing from a language that does not seek neutrality, but radical tenderness and provocation.

The #PeloBueno campaign has borne fruits of concrete resistance among Afro-descendant children who suffer bullying at school because of their hair. From the digital to the pedagogical, this campaign has generated spaces of pride and self-affirmation. With #SaladeLecturaAntirracista, every year the efforts to create Afrocentric libraries and cultural centres multiply, spaces that break with the hegemonic canon and sow other narratives in historically marginalized communities.

#CelestinaCordero succeeded in having libraries, schools and educational workshops named after this black pioneer of education in Puerto Rico, whose legacy had been silenced.

#EnnegreceTuProntuario has had a direct and sustained impact on the academy: many professors have made changes to their curricula thanks to the campaign, incorporating Afrocentric content, and many of them have invited me to their courses to engage with students. This collective and insistent work also contributed to a historic achievement: in December 2024, the Puerto Rico Department of Education adopted for the first time an Afrocentric and anti-racist curriculum.

Moreover, my link with the digital sphere is also formative and professional. Since 1999, as I have already mentioned, I have worked as a specialist in educational technology, and I have been an instructor of platforms such as Microsoft, Google and algorithm systems applied to education. I was one of the first graduates of the Microsoft Office Academy in Puerto Rico, and I was part of the team that trained nearly 4,000 teachers in the use of digital tools. That experience allows me to understand, from the inside, how the systems that shape the way we produce and consume knowledge work.

I build bridges between the literary and the digital because algorithms also tell stories. What is not named in them, does not exist. And that's why I'm interested in intervening, infiltrating their logics, using writing as a tool for dialogue -or dispute- with those structures. From my poetry to my Afrofuturist publications, I position myself as a creative who is not afraid of technology, but who approaches it from a critical, racialised, feminist and anticolonial perspective.

Let's talk a bit about afro-cyberactivism, these Afrocentric resistance movements that use the digital space as a means of dissemination and construction of knowledge and resistance... do you consider your literary practice as a form of afro-cyberactivism?

No doubt. I write books, but I also write tweets, manifestos, cyberliturgies. I do it in trance, I perform oracle literature and that is why I have even written an Afro bible entitled Cüiruba. My literary practice is not dissociated from the political act of occupying the digital space with our black voices, our memories, our contradictions. It is a form of Afro-ciberactivism that challenges the dominant white narrative, experimenting with new forms of community and care. But it is also Evaristo's Afro-scrivival. It is my life, I live what I write.

To conclude, how can literature become a tool for decolonialisation in the contemporary digital space?

Literature remains a fortress. In the digital, it also becomes a living archive, a performative act, a possibility for immediate response. Decolonial literature is not only that which denounces colonial violence, but also that which imagines futures where our black bodies are loved, technological, free. In that sense, writing in and from the digital can penetrate the traditional structures of the canon, the market, the state. Writing becomes an act of disobedience and collective healing.

Final Reflections: Towards Afrocentric Futures

The conversation with Yolanda Arroyo Pizarro reveals the scope of a literary proposal that transcends the boundaries between activism and art, between memory and future, between the local and the global. Her work invites us to reimagine the possibilities of resistance in the digital era, and demonstrates that Afro-Caribbean literature can serve as a laboratory for developing more refined strategies of social transformation.

Independent

IndependentAfroalgoritmo | Yolanda Arroyo Pizarro | Amazon | 120 pages | 16.00 USD

Arroyo Pizarro's literary-activist practice embodies the main strategies of contemporary Afro-cyberactivism, mentioned at the beginning of this article: making visible forgotten or untold stories and confronting them with other narratives, the construction of transnational networks through the strategic use of multilingualism, and the documentation or testimonies with a narrative agency. The continuum we observe from 'Las Negras' to 'Afroalgoritmo' is not accidental: the author's technological background places her in a unique position, allowing her the critical gaze that permeates her work. Her understanding that algorithms "reproduce colonial and racial biases" lays the groundwork for her proposal of literature as a technology of resistance.

The digital campaigns initiated emphasises the importance of giving visibility. #CelestinaCordero recovers silenced historical figures; #SaladeLecturaAntirracista builds translocal networks and connects dispersed communities; #PeloBueno allows Afro-descendant childhood to be positively valued. The concrete achievements attained by such campaigns show the transformative potential of digital technologies.

Finally, we would like to highlight Yolanda Arroyo Pizarro's conviction in defining her literary practice as Afro-cyberactivist, which reaffirms our idea that Afro-Caribbean literature indeed functions as an early form of Afro-cyberactivism. When she tells us of "cyberliturgies" and "oracle literature" she establishes direct connections between Afrodiasporic spiritual practices and digital technologies; while her reference to Conceição Evaristo's "Afroescrivivencia" situates her work within broader, ancestral genealogies of Afro-descendant literary resistance.

At a historical moment where digital technologies reproduce colonial and racial biases, Yolanda Arroyo Pizarro's proposal to "reclaim Afrodiasporic science fiction as our imaginative territory" is necessary and urgent. As she herself states: "We continue denouncing, writing, claiming, even if it hurts.

In this resistance woven between ancestral memory and digital future, between literature and activism, we find not only a new way of understanding Afro-cyberactivism, but an invitation to participate in the construction of a more just and free world.

This interview was conducted as part of my doctoral research where I explore how contemporary Afro-Caribbean literatures dialogue with emerging forms of digital resistance. Part of this work was presented at the II Congreso de Literaturas Hispánicas: Migraciones, diásporas, exilios y desplazamientos en las literaturas hispánicas del siglo XXI (Universidad de Villanueva - Universidad Internacional de La Rioja, June 23-25, 2025, Madrid, Spain).