On Not Reading Rizal

Caroline S. Hau was born in Manila, Philippines and educated at the University of the Philippines-Diliman and Cornell University. Seven of her books--among them Necessary Fictions: Philippine Literature and the Nation 1946-1980, Intsik: An Anthology of Chinese Filipino Writing, Interpreting Rizal, Recuerdos de Patay and Other Stories, and Tiempo Muerto: A Novel--received Philippine National Book Awards. She is a recipient of the Grant Goodman Prize in Historical Studies from the Philippine Studies Group of the Association of Asian Studies (U.S.A.) and the Gawad Balagtas lifetime achievement award from the Writers’ Union of the Philippines. She lives in Kyoto, Japan with her spouse and daughter.

A young Filipino’s initial encounter with national hero José Rizal’s novels, Noli me tángere (1887, popularly called Noli) and El Filibusterismo (1891, Fili), is more likely than not to be an off-putting experience.

For one thing, it happens in the classroom, which is often anything but a place of learning, if classrooms are available in the first place. Reading on assignment is not exactly a spark-joy kind of thing.

To be sure, for Filipinos, the proper name “José Rizal” (1861-1896) is freighted with hope, anxiety, doubt, and expectation. It is not enough that he be talented; he must be a prodigy, pride of the Malay race (many Filipinos, at least, draw the line at using the oxymoronic “Filipino race”). The Noli, written in Spanish and published when Rizal was twenty-five years old, and the Fili, published when he was thirty, are touted as masterpieces of Philippine literature and have enjoyed an exalted status akin to that of the nineteenth-century national novels of Latin America. These foundational texts have cast a long shadow over Philippine nationalism, shaped Filipino political and social thinking, and guided the development of Philippine literature in Filipino, English, and other Philippine languages.

Since 1956, the Philippine government has mandated the inclusion of courses on the life, works, and writings of Rizal in the curricula of all schools, colleges, and universities. Institutions of tertiary education are required to use original or unexpurgated editions of the Noli and the Fili, even as concessions to the Catholic Church allow for exemption from reading the novels on grounds of religious belief. Given that in 2023, only about sixteen percent of Filipinos (out of a population of more than 117 million) made it to college, it is safe to say that a substantial majority of Filipinos have not read the novels either in the original or in their entirety. High schoolers—a little over twenty percent of the population—are force-fed indigestible servings of Noli and Fili in their junior and senior years, while elementary school kids are handed candy-wrapped morsels of Rizal’s teachings in their Civics and Culture classes in Grades 1-3 and Geography/History/Civics classes in Grades 4-6.

The “unexpurgated” translations used in colleges during the 1960s to 1980s were not exactly unexpurgated either. Benedict Anderson has shown how the popular English translation by León María Guerrero tried to make the Noli and Fili palatable for “modern” readers, only to end up stifling the subversiveness of Rizal’s laughter, entombing the novels in a dead past, sanitizing their earthy and radical content, and cutting the reader off from local references and European allusions.

José Rizal | Noli Me Tángere | Ebook Version @Project Gutenberg

While José Rizal may not be read wholly or widely, if at all, he—at least his name and image—is ubiquitous. He is on the one-peso coin. His portraits adorn classrooms and postcards and stamps. There are memorials dedicated to him in Indonesia, Japan, China, Australia, the United States, Mexico, Argentina, Peru, Spain, Germany, France, Italy, Belgium, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, and the Czech Republic. In his motherland, a province, seven municipalities from the regions of Luzon in the north to Mindanao in the south, at least eleven educational institutions, and twelve streets are named after him. There are Rizal safety matches, soft drinks, liquor, vinegar, kerosene, cement, cigars, clothing, bedding, accessories, stationery, toys, banks, insurance companies, sports stadiums, hospitals, and funeral homes.

For all the Philippine government’s efforts to familiarize its citizens with the life, works, and writings of Rizal, the writer and his novels remain elusive and retain an ineluctable foreignness.

(1) I thank Jojo Abinales and Leloy Claudio for their comments. (Letter to Mariano Ponce, 30 September 1888)

Although Rizal once told a friend that the Noli “has been written for the Filipinos, and Filipinos need to read it” (se ha escrito para los filipinos, y es menester que los filipinos la lean) (1), he wrote in Spanish, a language that, by the time he was executed on charges of being the “author” (autor in the double senses of writer and instigator) of the Philippine Revolution of 1896, was fluently spoken by only about three percent of the population. Most Filipinos now read Rizal only in translation (and likely only in English or Filipino).

Rizal had spent the better part of his adult life abroad, in Europe, the United States, and parts of Asia. His novels were published in Berlin and Ghent, respectively. Not for nothing are the Noli’s two heroes, Juan Crisostomo Ibarra and Elías, consummate polyglots. The first chapter of the novel makes it clear that Ibarra can speak the languages of the countries he has lived in (including English, German, French, Russian, Polish). Elías, a Tagalog, surprises Ibarra on their first meeting by speaking fluent Spanish and has presumably picked up several other local languages from his extensive travels across Philippine provinces.

In fact, one of the main goals of the Propaganda Movement, apart from advocating for Filipino representation in the Spanish Parliament (Cortes), had been to challenge the epistemic authority of race-based colonial privilege. This entailed a plethora of activities: learning languages other than Spanish; writing essays for the journal, La Solidaridad; delivering papers at learned scientific societies; publishing novels and scientific, historical, ethnographic accounts; and networking with friends and liberal allies in Spain and other places to create a common cause. Present-day Filipinos are necessarily polyglot by virtue of the multitude of languages (between 120 and 187) spoken in the Philippines and their long experience of living and working abroad. Filipino elites, however, are heavily dependent on Anglo-American publishing and academia for news, information, and analysis, and on the English language for conversation among themselves and communication other than orders and campaign speeches with other Filipinos.

(2) Letter to Ferdinand Blumentritt, 13 April 1887

Too, ideas, mores, standards, values, and sensibilities change, most evidently in the changing meaning of the word “Filipino,” which had originally referred to Spaniards or Spanish-Filipino mestizos born in the Philippines. Rizal and his fellow ilustrados (enlightened, educated) played a role in resignifying the term. Of his circle in Madrid, he wrote that “these friends are all young men, creoles, mestizos, and Malays; we simply call ourselves Filipinos” (diese Freunde sind alle Jünglingen [sic], créolen, mestizen, und Malaien, wir nennen uns nur Philippiner [sic]). (2)

Even more telling, the evolution of the status of Filipino women in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries accounts for the fact that, of all the major characters in the Noli, it is the ill-fated María Clara–daughter of a priest, object of lust by another who frames her fiancé Ibarra for rebellion—who has served as a cultural lightning rod. Held up by some as an exemplar of feminine beauty and virtue, she is vilified by others for being weak and foolish. Dismissed by some feminists for being a relic of the past, she yet haunts Filipino art and literature. Above all, she is relentlessly commodified, her name affixed to wine, sweets, condiments, jewelry, fashion, cosmetics (including underarm whitening cream), beauty-pageant walk, Barbie® doll, sanitary napkin ad campaign, dance suite, heritage events, restaurants, lodgings, and museums. In downtown Manila, two intersecting streets are named after Ibarra and María Clara.

The importance of the Noli and the Fili arguably resides in the impact these novels have had on those who could not, did not, or have not read them.

This was certainly the case in Rizal’s time. Only a small number of the two thousand printed copies of the Noli found their way into the Philippines. Official censorship, denunciation by the religious orders, and Rizal's inept handling of the distribution limited the circulation of the novel to small circles of Spaniards or Spanish speakers and literate Filipinos.

(3) Letter to Ferdinand Blumentritt, 5 September 1887

Rumors played a far more crucial role in cementing Rizal’s reputation and disseminating in some form or another the content of the novels among those who neither knew Rizal personally nor could get their hands on his books. In 1887, Rizal reported being taken for a German spy, an agent of Bismarck, a Protestant, freemason, wizard (Zauberer), and half-damned soul (halbverdammte Seele). (3) News of the newly arrived “German doctor” (Doctor Uliman) generated popular excitement and tales of miraculous cures. The man himself, dressed in a western suit and hat, pale from years in northern climes and afflicted with prickly heat, appeared foreign to his own people.

A similar air of mystery surrounds the Noli’s Ibarra, who, after escaping from prison with the help of his friend Elías and wandering the world for thirteen years, returns to the Philippines in the Fili in the guise of a jeweler named Simoun intent on fomenting revolution for real. Ibarra adopts as his nom de guerre the Arabic-derived French term for the powerful desert wind, the root word of which, sm(m) س م م , means “to poison” in Arabic, but can also denote both “poison” and “medicine” in Aramaic and Syrian. The simoun wind, a recurring trope in Oriental-themed art and literature, is retooled by Rizal as a figure of the anti-colonial, revolutionary sublime, a metaphor for resistance against attempts to assert European colonial/imperial subjectivity and impose its cultural values upon the world. The cosmopolitan Simoun is predictably (mis)taken by various people for a Yankee, an Anglo-Indian, a Portuguese, an American, a mulatto, an American mulatto, though early on in the Fili he reveals his true identity to the young doctor Basilio (and, of course, to the reader). Simoun’s status, like his creator’s, as an insider-outsider, a “foreigner” who is also a “Filipino,” proves socially disruptive and politically destabilizing.

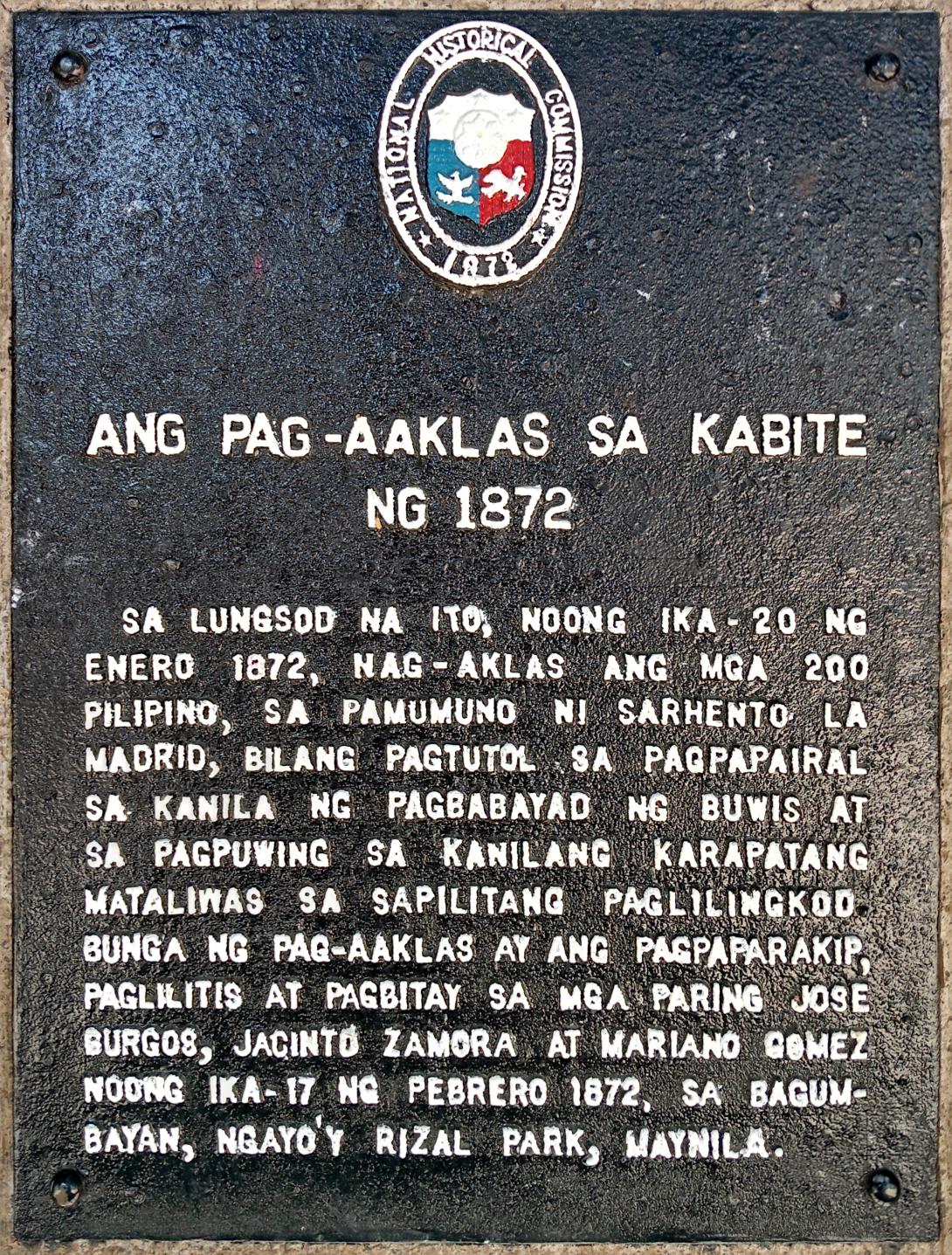

RalRalff Nestor Nacor, CC BY-SA 4.0

RalRalff Nestor Nacor, CC BY-SA 4.0The historical marker installed in 1972 by the National Historical Commission at Samonte Park to commemorate the mutiny of 1872.

Moreover, Rizal’s novels explicitly highlight the role that commentary and speculation play in colonial society. They simultaneously conjure and question community through their frequent depictions of crowds, who are not mere onlookers, but movers and doers and commentators and rumormongers. The novels regularly invite readers to eavesdrop on these conversations. A chapter in the Noli entitled “Rumors and Beliefs” records the lively conversations among the townsfolk in the wake of the fake rebellion. A chapter in the Fili entitled “Commentaries” details people’s varying reactions to news of the tragedies that befall a character’s family. In another Noli chapter entitled “Comments,” the news that Ibarra had laid his hands on Padre Dámaso, María Clara’s real father, is greeted first with incredulity, and then, observes the narrator, “each one made his or her commentaries according to his or her own degree of moral elevation” (Cada uno segun el grado de su elevación moral hacía sus comentarios). The chapter ends in a scene in which a group of rural folk ponders the meaning of filibustero, a term associated with piracy, political adventurism, American expansionism, and revolution in the Caribbean and Latin America that first entered the Philippine lexicon by way of Cuba (then in the throes of the Ten Years’ War [1868-1878]), in the wake of the 1872 mutiny that broke out in the Cavite arsenal southwest of Manila.

Rumors swirl in kitchens, bedrooms, parlors, servants’ quarters, back of churches, in steamers, shops and markets, and government offices. Rumormongering involves acts of speaking, interpretation, and passing on of information by those who are not authorized to hear about important matters, let alone make themselves heard. Rumors have little if anything to do with the truth yet possess the power to cast doubt on the authorities that reserve for themselves the right to determine who can or cannot hear and who can or cannot speak. Information gleaned from rumors—incomplete, fragmentary, decontextualized, inaccurate—is filtered through personal and community experience and knowledge. Adds the narrator: “The fact, distorted into a thousand versions, was believed with more or less facility according to whether it suited or ran contrary to each person's passions and mode of thinking” (El hecho, en mil versiones desfigurado, fué creido con más ó menos facilidad segun adulaba ó contrariaba las pasiones y el modo de pensar de cada uno).

The Noli and Fili assiduously collect and relay gossip, rumors, conversations, debates. The reader hears everything and is assigned the task of making sense of the unfolding events and the responsibility of sifting fact and truth—an exercise in intellectual autonomy. In the first chapter of the Noli, the narrative persona’s fourth-wall invocation of “oh, you who read me, friend or foe!” (¡oh tú que me lees, amigo ó enemigo!) presumes a small readership, literate in Spanish, possessed of sufficient Western-style education to recognize classical, Christian, and European references, and appreciative of the novel’s strategic use of Tagalog vocabulary and mainly Tagalog local references.

For Rizal, the meaning of “community”—a crowd that is aware of its purpose and behaves as a collective actor to achieve that purpose—has proven particularly fraught because neither colonial Filipinas nor the world can be understood in terms of a romanticized linguistic utopia of shared language, knowledge, values, and worldviews. Instead, highly asymmetrical power relations between and within countries are enforced by everyday physical and epistemic violence.

The tension between “proper,” “correct” ways of reading the novels and the openness of these novels to being interpreted according to the variegated interests and moral precepts of whoever reads them is powerfully thematized in Rizal’s dedication, “A mi Patria,” in the Noli. Here, Rizal stresses the revelatory function of the novel to reproduce the state of the Patria as faithfully as possible (trataré de reproducir fielmente tu estado sin contemplaciones) by “lift[ing] a part of the veil that covers the evil, sacrificing everything to the truth, even pride itself, for, as your own son, I, too, suffer from your defects and shortcomings” (levantaré parte del velo que encubre el mal, sacrificando á la verdad todo, hasta el mismo amor propio, pues, como hijo tuyo, adolezco tambien de tus defectos y flaquezas). Rizal offers an analogy for how he intends to go about diagnosing the ills of his country:

Deseando tu salud que es la nuestra, y buscando el mejor tratamiento, haré contigo lo que con sus enfermos los antiguos: exponíanlos en las gradas del templo, para que cada persona que viniese de invocar á la Divinidad les propusiese un remedio.

Desiring your welfare, which is our own, and seeking the best treatment, I will do with you what the ancients did with their sick: they exposed them on the steps of the temple so that everyone who came to invoke the Divinity could propose a remedy.

The practice of bringing the sick to temples to implore Divinity for a remedy is typical of the healing temples founded by followers of Aesculapius in Greece and later Rome. Here, the sick perform rituals and spend the night in a temple in hopes that medical advice will be dispensed to them in their dreams directly by the gods or, failing that, by the temple priests. But the countervailing practice of the sick soliciting advice not from the gods and their authorized representatives but, rather, from the general populace in a public square is attributed by Herodotus to the Babylonians. (Historians have, of course, refuted Herodotus' contention that Babylonians did not consult doctors.)

It appears that Rizal melded the “Greek” and “Babylonian” traditions in his dedication, placing the sick on temple steps (Greece) to solicit advice from the public (Mesopotamia). Rizal's apparent mistake or confusion is felicitous, as the novels draw their torsional force from the competition and mutual undercutting between a hierarchical understanding of reading that prescribes “correct” and “proper” ways of arriving at the meaning of the text, and a demotic—arguably democratic—understanding of reading that is open to individual meaning-making and interpretation according to particular agenda, interests, and moral lights.

This openness of Rizal’s novels—the openness of all classics—to multiple interpretations accounts for their longevity. The brouhaha that has surrounded the novels and their author over many decades is testament to “misreadings” being productive and creative rather than merely distortive and disabling. More importantly, misreading has real-life effects. At his trial for treason, Rizal tried to defend himself by arguing that he had been misread by the Spanish colonial authorities that sought to attribute authorship of the 1896 Philippine Revolution to him as well as by the revolutionary organization, the Katipunan, which had drawn inspiration from his writings and used Rizal’s name as a battle-cry to rally its members despite Rizal’s refusal to give his blessings to its planned uprising. The prosecution argued that Rizal was no less than the Word of Revolution (el Verbo del Filibusterismo) precisely because of the capacity of his writings to stoke dormant resentments and raise hopes for the future. The openness of Rizal and his novels to (mis)interpretation has in turn generated substantial commentary in different media and languages across space and time, even as Rizal’s most avid readers fret over the novels remaining largely unread or “misunderstood” by Filipinos. Such openness also means that while the Philippine state has repeatedly invoked and marshaled Rizal for its own purposes, no political force can completely claim Rizal.

Most of all, Rizal’s novels continue to circulate through transmedia storytelling. As stories cross multiple texts, media, and publishing platforms, they undergo such changes as to be no longer strictly dependent on their original source texts. Rizal’s novels are principally read by present-day Filipinos in multiple genres, formats, and platforms—in comic books, school skits, social media, film, television, stage, song, dance, visual and plastic arts, commodities, heritage sites, official commemorations, and civic events. These adaptations and interpretations often give birth to new stories and new characterizations that may or may not any longer refer back to Rizal’s original creation and story. Recent fictional re-imaginings of María Clara, far from imprisoning her in the archaic Victorian mold, have recast her in the role of social worker, pre-school teacher, medical doctor, LGBTQ lover, even thief and sex worker.

IMDb

IMDb

In the hit television portal-fantasy series María Clara at Ibarra (2022-2023), a college student falls asleep in the middle of a class discussion on the Noli. Scolded by her teacher and, as punishment, assigned to write and present a book report, María Clara “Klay” Infantes (who, apart from sharing her given name with Rizal’s tragic heroine, sports an allegorical surname that, in Spanish, means “young children”) resentfully declares that she doesn’t “get” (gets) the significance (saysay) of the school subject for her nursing course and her dream of working and living permanently abroad. Her teacher lends her an antique copy of the book—different from the textbook they are using in class—and Klay falls asleep while reading the book. She wakes to find herself magically transported to the fictional universe of the Noli and Fili. Klay gets to play reader, critic, lead character, and author who ultimately rewrites the Noli and the Fili by changing their plots.

The plot changes in a soap opera like María Clara at Ibarra reveal much about how differently Filipinos re-imagine the nineteenth century Philippines. The Spanish-mestizo Ibarra is played by an actor who, like Rizal, is also of Chinese ancestry. María Clara, now viewed as a product of rape (even though the original Noli leaves open the possibility of a seduction, even a love affair, between her parents), dies from a gunshot wound, not a lingering illness. The villainous Padre Salví doesn’t escape punishment. The Chinaman Quiroga is no longer a money-grubbing, opportunistic alien, but Simoun’s friend and fellow conspirator. Elías evades the tragic fate that Rizal had originally destined for him. Whereas Simoun’s revolution was thwarted in the Fili, a revolution does indeed break out here and Elías is part of it. Simoun takes poison and confesses his identity to Padre Florentino, but in this retelling, he dies surrounded (and mourned) by Klay, Elías, and Basilio. María Clara’s Gen Z-generation namesake, Klay, returned from abroad after training as a medical doctor (like Rizal himself), meets the present-day reincarnations of Ibarra and María Clara, a college professor and a music teacher.

The popularity of this TV adaptation—a welcome change from its earnest, if plodding, predecessors—has inspired some youngsters to seek out unabridged versions of the novels. For many young Filipinos, the nation is to some extent already a given. To argue the givenness of the nation for segments of the Philippine population in no way downplays the nation-state’s persistent logic and politics of inclusion and exclusion and the reality of continuing discrimination against, and marginalization of, individuals and communities—women, indigenous peoples, Muslims, LGBTQ+, ethnic Chinese, people with disabilities, among them. Because the dream of a unified Pilipinas remains elusive, it is continually posited, reinforced, and interrogated.

In Conjectures on World Literature (2000), Franco Moretti wrote of the technical difficulties that Rizal confronted in imagining the nation “whole,” noting that the “oscillating” (“between Catholic melodrama and Enlightenment sarcasm”) voice of Rizal’s narrator was owing to the breadth of the social spectrum that the novels were tasked to encompass. “[I]n a nation with no independence, an ill-defined ruling class, no common language and hundreds of disparate characters, it’s hard to speak ‘for the whole’, and the narrator’s voice cracks under the effort.” Rizal’s novels explicitly foreground the difficulty—the ever-present risk of failure—of imagining and making community, especially a national one. Far from being a problem that mainly afflicts the developing world, the fragility of the national project has added resonance in the present, in light of the current polarization of politics within and across the developed world and the high-stakes contestation, in the very countries that claim they have either achieved the proper status of a nation or, even better, transcended it, over what, and whose, country it is and who has the right to live in it and speak for it.