Domination and resistance

Maja Zwick is a sociologist specialising in the Western Sahara conflict, transnational mobility and protracted refugee situations in the Global South, particularly the Sahrawi refugee camps in Algeria, where she has conducted extensive field research. She completed her doctorate at the Free University of Berlin on the relationship between place and belonging in the context of flight, migration and return. Her research combines social anthropological, postcolonial and decolonial approaches with participatory qualitative methods. Her work has been funded by the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation and the DAAD.

The 14th of November this year marked the 50th anniversary of the illegal Madrid Accords, by which Spain transferred administrative control of its colony Western Sahara to Morocco and Mauritania. This act facilitated the annexation of Western Sahara, already underway since late October 1975. While Mauritania withdrew in 1979, Morocco today occupies more than 80 percent of Western Sahara. Spain has failed to fulfil its decolonisation responsibility to this day.

The recent adoption of UN Security Council Resolution 2797(2025) on 31 October 2025 adds a new layer to this unresolved colonial legacy. For the first time, the resolution explicitly endorses Morocco’s autonomy plan as a “serious and realistic basis” for resolving the conflict. This violates the international status of Western Sahara as a decolonisation issue and marks a significant shift from how the Security Council has previously addressed the issue in accordance with the principles anchored in the United Nations Charter. Thus, the resolution deepens the contradiction between Spain’s historical responsibility and the UN’s evolving position, as it effectively legitimises an occupation that originated in the unlawful transfer of power fifty years ago (1). While Spanish civil society supports the Saharawi people’s right to self-determination and independence, the Spanish government continues to stand with Morocco (2), reinforcing the unresolved moral and political debt of 1975.

This essay addresses one of the most enduring traces of Spanish colonial rule: the Spanish language. Besides Equatorial Guinea, Western Sahara is the only hispanophone country in Africa. Although Spain withdrew in 1975, its language continues to circulate through migration, education and media – producing a layered field where colonial remnants, anticolonial resistance and new solidarities intersect. Thus, Spanish mirrors the unfinished process of decolonisation of Western Sahara.

Postcolonial legacies of colonial languages

Colonial and postcolonial contexts are marked by hybridity of local and colonial languages, that often carry ambiguous meanings for political and cultural belonging. Language is a profound expression of historical and contemporary power dynamics, particularly evident in European colonial languages, as these served as crucial instruments of colonial dominance while marginalising local languages. In Pierre Bourdieu’s terms, colonial languages embodied both symbolic power and brute violence (3). As bell hooks (4) observes, Standard English still echoes the terror and violence of slavery, and colonial languages continue to reproduce racism and hierarchies in knowledge systems and everyday life (5). Paradoxically, however, they also became spaces of resistance and coordination for national liberation movements (6), captured in Frantz Fanon’s notion of colonial language as both “language of the occupier” and “instrument of liberation” (7).

Post-independence, language became crucial in the national and regional politics of belonging of the newly independent states (8). While some states replaced colonial languages with local languages, others retained them as linguae franca, especially in multilingual contexts. In such cases, however, they often remained the preserve of the elite, who relied on them to gain access to economic and social privileges (9).

Against this background, Western Sahara’s linguistic situation is uniquely complex. Part of the population lives under Moroccan occupation, part has spent five decades in self-managed refugee camps in Algeria under their government-in-exile, the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), and part is dispersed around the world, mainly in Spain. While Hassaniya Arabic remains central to Saharawi belonging, Spanish has assumed a new, ambivalent role examined in the following sections.

Languages in Western Sahara

Western Sahara is part of the North-West Africa region known as the “Saharan West” (10), or trāb al-bīḍān. This region extends from the southern Algerian-Moroccan border area to the northern banks of the Senegal River and from the Atlantic Ocean coast to the edge of the settlement areas of the Tuareg in northwestern Mali (11). The inhabitants share common social norms, cultural practices, and the Hassaniya language, which is closely related to Standard Arabic and has been the lingua franca of the region since the 19th century following Arabisation and Islamisation (12). Today, Hassaniya is spoken in Western Sahara, Mauritania, south-western Algeria, southern Morocco, and parts of Mali and Niger.

When the European colonial powers established the rules governing their conquest and colonisation of Africa at the Berlin Conference of 1884/85, Western Sahara was awarded to Spain. However, effective colonial control was not established until 1934, under pressure and with the help of France. Spain’s strategic interest in the area only began to grow in the late 1950s, mainly because of its rich phosphate deposits. To evade UN decolonisation demands, General Franco declared Western Sahara a “Spanish province” in 1958, yet an educational system was not implemented until the 1960s, primarily benefiting Spanish male settlers in the phosphate industry (13). Since Western Sahara was a military colony and, as a “colonia de explotación mercantile”, only of interest from an economic and geopolitical perspective, there was no consideration of introducing Spanish “culture” or a Spanish education system (14). According to the 1974 Spanish census, only 11.5 percent of Saharawis under the age of 24 were enrolled in school, and 13 percent of those over the age of five were literate in Spanish (15). However, these statistics may be inaccurate, as the nomadic lifestyle of many complicated the colonial administration’s efforts to count and control them. In school, Spanish teachers taught a glorified version of colonial and fascist Spain, while Saharawis were largely excluded from discussions on decolonisation (16).

Private

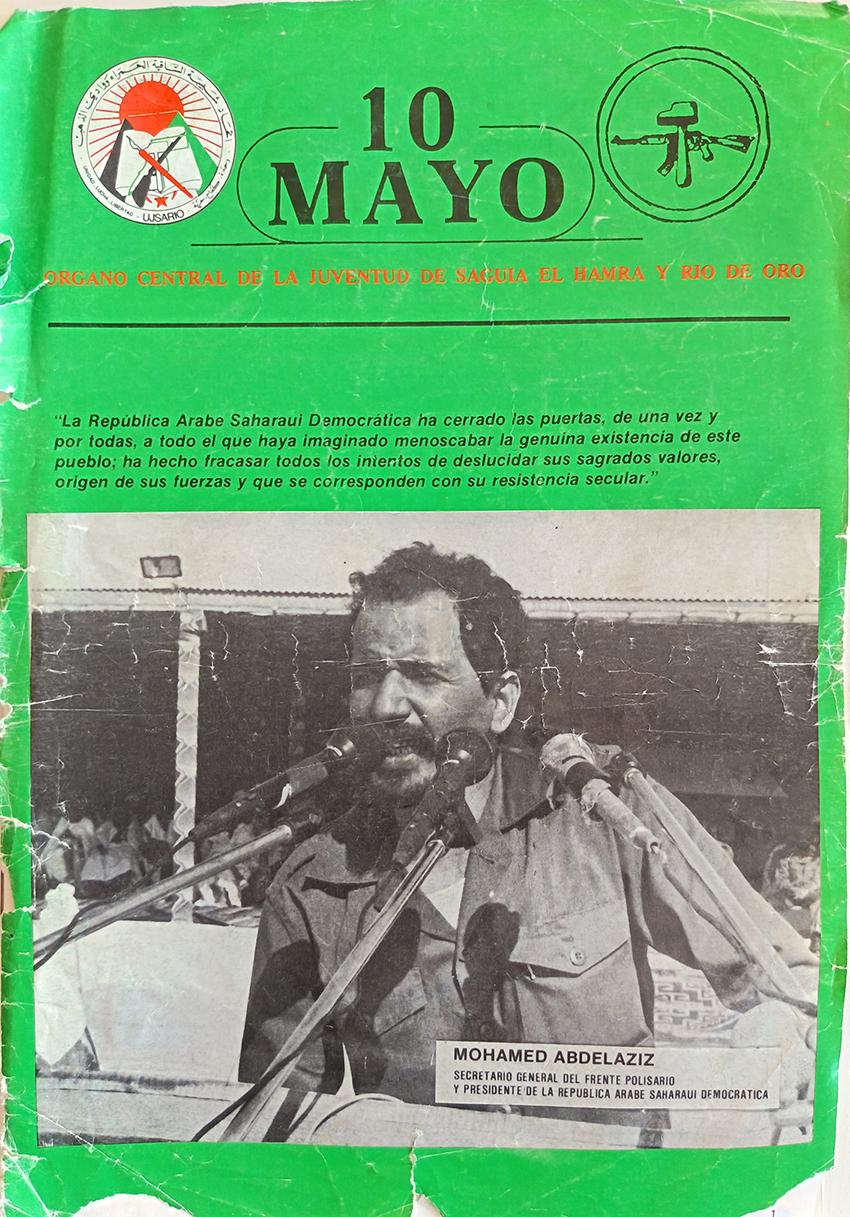

PrivateThe central organ of the Saharawi youth organisation UJSARIO, titled “10 Mayo” after the founding date of Frente POLISARIO, was published in Spanish.

Spanish in the anticolonial struggle

Despite the low level of Spanish literacy among the Saharawi population, the liberation movement Frente POLISARIO (17) also adopted a Spanish name. This reflected the common strategy of liberation movements of that time to counter colonialism through its own linguistic means. Spanish is recognised as the second official language of the SADR, taught in schools in the refugee camps from the third grade, and widely used in publications (18). For instance, the central organ of the Saharawi youth organisation UJSARIO (19), titled “10 Mayo” after the founding date of Frente POLISARIO, was published in Spanish (see right).

Besides, belonging to the Spanish-speaking world distinguishes the Saharawi nation within the predominantly Francophone Northwest Africa. Spanish thus serves as a reference to the specific Saharawi colonial experience and as an important marker of Saharawi national identity, which Morocco has long sought to erase by portraying the Saharawis as inherently Moroccan and the Frente POLISARIO as an Algerian proxy holding them captive in the refugee camps. This propaganda supports Morocco’s occupation of Western Sahara which is rooted in the aggressive nationalist ideology of a “Greater Morocco” (20).

In its founding communiqué, the Frente POLISARIO aligned the Saharawi people with the “Arab nation” and considered itself as “part of the Arab revolution”, while also affirming its African identity (21). However, support from the Arab world has been minimal. Apart from Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Yemen, Syria – which recognised the SADR – and initial support from Lebanon, many Arab nations have remained indifferent or have openly supported Morocco, including the Gulf and Jordan monarchies but even the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) (22). In contrast, the SADR has received significant support from African states, gaining admission to the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in 1982 and becoming a founding member of its successor, the African Union (AU).

At the same time, the Frente POLISARIO has cultivated diplomatic ties with Latin American states and movements, employing Spanish from the outset as a medium that reflects shared linguistic and colonial heritage (23). This shared history and commitment to anti-imperialism and anticolonialism facilitated transnational solidarity and led to the recognition of the SADR by most Latin American countries. In addition to its membership in the AU, the SADR participates in various transnational and transregional forums, including the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), the New Asian-African Strategic Partnership (NAASP), COPPPAL (the Permanent Conference of Political Parties of Latin America and the Caribbean), the Andean Community of Nations, and the Ibero-American Summit.

The Cuban influence

One of Latin America’s most steadfast supporters has been Cuba, which officially recognized the SADR in 1980. However, Cuba’s involvement dates back much earlier. In 1975, the Frente POLISARIO reported to the Cuban Communist Party (PCC) on the situation in Western Sahara (24) In 1976, Cuban doctors and teachers began working in the refugee camps, and by 2002, 477 health professionals had participated in Cuba’s internationalist missions there (25).

More impactful, however, was Cuba’s educational migration programme for Saharawi children and youth. During the Cold War, Cuba promoted a model of development that emphasised the common colonial legacy and solidarity among the countries of the Global South, offering an alternative to Soviet dependency and neo-colonial North-South hierarchies (26). This included South-South cooperation programmes to support socialist states and anti-colonial movements. The International Education Programme, which was launched in 1961 and continues to this day despite the enormous constraints imposed by the US embargo, has awarded full scholarships to tens of thousands of students from the Global South. Between 1961 and 2008 alone, over 55,000 children and youth from more than 148 countries completed their education at secondary schools, vocational schools, colleges and universities in Cuba (27).

Since 1977, several thousand Saharawi children and adolescents have participated in this programme (28). Pablo San Martín notes the influence of this group, which constitutes a large percentage of the younger professionals and cadres within the SADR (29). Many SADR/Frente POLISARIO ministers and diplomats received their education in Cuba (30).

Most Saharawis spent over a decade in Cuba, completing their education within a socialist framework that emphasised equality and collective solidarity, epitomised by José Martí’s maxim: “Compartir lo que tienes, no dar lo que te sobra” (“Share what you have, not give what you have left over”). This principle shaped the young Saharawis’ sense of belonging (31). The children overcame their initial feelings of homesickness and material deprivation by supporting each other within their peer group, transforming Cuba from a second exile into a home, albeit a provisional one. As Saharawi poet Liman Boicha recalls (32), some felt part of the ajiaco criollo, a symbol of Cuba’s transculturality described by Fernando Ortiz. This dish, composed of a variety of fresh and dried meats, legumes, and vegetables, reflects the complex composition of cultural influences in Cuba – Indigenous, African, European, North American, and Asian. Ortiz argues that the ajiaco is always evolving, with its colourful ingredients constantly blending and dissolving into a rich broth, thus serving as a metaphor for the ongoing process of Cuba’s transculturación (33). While Ortiz introduced transculturación as a counterpoint to Eurocentric acculturation, the Cuban Revolution further framed this hybrid identity in political and ideological terms associating Cubanidad with internationalism, anti-imperialism, and solidarity.

Returning to the camps after many years abroad, the young Saharawis found themselves personally, culturally and linguistically transformed, but also their place of origin profoundly changed. This led to the paradox of return, of arriving at a place that is both unknown and known (34). Much of their socialisation had taken place in Cuban society, whose values differed significantly from the Saharawi exile community. This contrast gave rise to contradictions upon their return, distinguishing them as a unique group known as the Cubarawis. This neologism blending “Cubano” and “Saharawi” captures the hybrid sense of belonging of many returnees (35). In the often painful process of their re-emplacement, language played a crucial role. Because Spanish had served as the lingua franca among international students in Cuba, many Cubarawis now felt more comfortable speaking Spanish, often mixing it with Hassaniya, creating a linguistic blend known as Hassañol. Initially ridiculed, this hybrid language helped them cope with their experience of migration and return and became a marker of their distinct experience (36).

The returnees contributed to a kind of hispanidad in the camps, evident in the spread of Spanish in daily life and initiatives like the Spanish-language news programme on RASD TV, founded by a Cubarawi. The Cubarawis comprised the majority of Spanish teachers in the schools of the camps and shaped the public space, for instance by opening restaurants and internet cafés (37). Spanish terms have become ubiquitous among refugees, often leading to hybrid language formations. For example, mantas, the Spanish plural of manta (blanket), has evolved into the Hassano-Spanish plural lemānt. Similarly, cucharas (spoons), has adapted to the Hassaniya plural al-cuachīr, while cama (bed) is declined in Hassaniya, for example as camtu (his bed). Linguistic hybridity extends beyond Spanish influences; Saharawi tea, for instance, is occasionally made on a small electric hotplate, ar-rišū, a term borrowed from Algerian language (from French réchaud).

The case of the Cubarawis illustrates how Spanish became a medium of solidarity, education, and transnational belonging, rather than merely a colonial residue. Unlike postcolonial contexts where linguistic hybridity stems from colonial relationships, Spanish in Western Sahara reflects Latin America’s anticolonial solidarity, particularly that from Cuba. The Saharawi experience embodies a South-South hybridity grounded in solidarity, utilising the former colonial language not as a “booty of war” (butin de guerre) as Kateb Yacine posited regarding French in Algeria, but as a shared tool of anticolonial struggle.

Moreover, the experiences of the Cubarawis suggest a unique hybrid belonging that challenges traditional postcolonial frameworks, such as Homi Bhabha’s “Third Space” (38). Unlike Bhabha’s model, which is based on the coloniser–colonised dynamic, the Cubarawi case highlights postcolonial hybrid identities which are rooted in anti-colonial South–South cooperation, rather than in metropole–periphery hierarchies. However, the current influence of Spanish should not be viewed solely through the lens of South-South solidarity, as it also reflects emerging transnational ties to Spain – an aspect that underscores the ambivalence of Spanish in the Saharawi context.

Transnational and neocolonial entanglements – Spain’s postcolonial presence

Since the late 1990s, Spain has emerged as a key destination for Saharawi migration from both the refugee camps in Algeria and the Moroccan-occupied Western Sahara. The migratory route between the occupied territories and the Canary Islands intensified, with an increasing number of wooden boats – the infamous pateras – carrying Saharawis fleeing social and political oppression (39). Following the Intifāḍa al-istiqlāl of 2005, the Moroccan authorities forced Sahrawi youths to make these dangerous crossings, during which many drowned or were reported missing (40). In the camps, the political stalemate and dwindling humanitarian aid pushed many to leave in search of work and stability to support their families. Most migrants were highly educated, often trained in Cuba or other countries allied with the SADR/Frente POLISARIO, yet many ended up in precarious informal jobs, with men working in agriculture or construction and women in restaurants or domestic service, sometimes without legal status. Only those with Cuban degrees – fluent in Spanish and graduates of the country’s prestigious medical schools – had the best chance of finding employment in the Spanish health sector, albeit after long bureaucratic struggles (41). Consequently, Spain, the former colonial power, not only benefited from Western Sahara’s unfinished decolonisation by absorbing cheap Saharawi labour, but also paradoxically by reaping the fruits of Cuba’s anticolonial educational solidarity.

On the other hand, transnational migration between the camps and Spain has continued to evolve, with improvements in residence regulations and living conditions for Saharawis. Spain has also become a site of transnational political commitment where Saharawi organisations mobilise solidarity for the Causa Saharaui. This transnational commitment is expressed literarily through the Generación de la Amistad (Generation of Friendship), a group founded in 2005 by Sahrawi poets educated in Cuba and later settled in Spain. Writing exclusively in Spanish, they aim to convey the suffering of their people under Moroccan occupation and to advocate for the liberation of Western Sahara. Their name reflects their gratitude for Cuban solidarity (42), while their literary use of Spanish articulates a form of long-distance nationalism that connects the diaspora with both the refugee camps and their occupied homeland.

Linguistic oppression and resistance in the occupied territories

In the occupied territories, language has become a site of both oppression and resilience. Moroccan authorities suppress Hassaniya, prohibiting its public use while promoting Moroccan dialects in institutions and schools (43), where children face harassment and punishment for speaking their native language. This repression is part of Morocco’s policy of “Moroccanization” of Western Sahara, which for five decades has sought to erase Saharawi culture and national identity, resulting in a slow genocide (44).

Yet, amidst this linguistic repression, language becomes an instrument of resistance. Saharawi activists insist on speaking Hassaniya or Spanish in court, and clandestine schools continue to teach children in both languages (45). In this context, Spanish functions as a political and affective medium of anticolonial struggle – the language of the former coloniser turned against the current occupier.

Conclusion

This essay examined Spanish in Western Sahara across four intertwined dimensions. Initially the language of the colonial occupier, it was later transformed into a medium of resistance and a conduit for transnational South-South solidarity. Through Cuban education programmes, it fostered a distinct Hispanidad in the refugee camps. Thus, unlike many postcolonial contexts, its presence in Saharawi society stemmed not from the continuing influence of the former coloniser but from anticolonial South-South solidarity. However, ongoing migration to Spain has sustained the use of Spanish in the refugee camps while also forging new neocolonial entanglements, where Spain indirectly profits from Cuba’s anticolonial efforts. In the Moroccan-occupied territories, both Hassaniya and Spanish act as instruments of resistance. Collectively, these instances reveal the complex and ambivalent role that Spanish has played in the Saharawi experience, mirroring, on the one hand, the protracted blockade of the decolonisation of Western Sahara and, on the other, the political and cultural resilience of Saharawi communities suffering under colonial and neocolonial oppression. In this context, hybridity emerges from the intersection of anticolonial South-South relations (Cuba), colonial, postcolonial, and neocolonial dynamics (Spain), and ongoing colonial violence (Morocco). Thus, language remains both an instrument of domination and a medium of political resistance. These various uses of the Spanish language across different contexts invite critical reflection on language and language policies in postcolonial societies.

+++

Did you enjoy this text? If so, please support our work by making a one-off donation via PayPal, or by taking out a monthly or annual subscription.

Want to make sure you never miss an article from Literatur.Review again? Sign up for our newsletter here.

(1) Hans Corell, Letter dated 29 January 2002 from the Under-Secretary-General for Legal Affairs, the Legal Counsel, addressed to the President of the Security Council, 2002, p.2.

(2) Jacob Mundy, “Book Review: The Ideal Refugees: Gender, Islam, and the Sahrawi Politics of Survival”, Refuge: Canada’s Journal on Refugees, Vol. 31, No. 1, 2015, 77–79.

(3) Pierre Bourdieu, Sozialer Sinn, Kritik der theoretischen Vernunft, Frankfurt a.M, Suhrkamp, 1993, p. 244; Stephan Moebius, Angelika Wetterer, “Symbolische Gewalt”, Österreichische Zeitschrift für Soziologie, Vol. 36, No. 4, 2011, 1–10.

(4) bell hooks, Teaching to transgress, Education as the practice of freedom, New York, Routledge, 1994, p. 169.

(5) Susan Arndt, Nadja Ofuatey-Alazard, Wie Rassismus aus Wörtern spricht, (K)Erben des Kolonialismus im Wissensarchiv deutscher Sprache: ein kritisches Nachschlagewerk, Münster, Unrast Verlag, 2011.

(6) hooks, Teaching to transgress, p. 169; Jürgen Osterhammel, Jan C. Jansen, Kolonialismus, Geschichte, Formen, Folgen, München, C.H. Beck, 2017, pp. 107–108.

(7) Frantz Fanon, Aspekte der Algerischen Revolution, Frankfurt am Main, Suhrkamp, 1969, p. 62.

(8) Brigitte Jostes, “Sprachen und Politik, Kulturerbe und Politikum”, Südwind, No. 10, 2008.

(9) Ulrike Mengedoht, “Die Sprache des Brotes, Frankophonie und Arabisierung in Algerien”, Blätter des iz3w, No. 247, 2000, 33; Werner Ruf, “Algerien zwischen westlicher Demokratie und Fundamentalismus?”, Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, B 21, 1998, 27–37.

(10) Alice Wilson, 1742431079 Sovereignty in Exile, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017, p. 21.

(11) Sophie Caratini, “La rôle de la femme au Sahara occidental”, in: La république des sables, Anthropologie d’une révolution, Sophie Caratini (eds), Paris, Budapest, Torino, L’Harmattan, 2003, p. 98.

(12) Tony Hodges, “The origins of Saharawi nationalism”, Third World Quarterly, Vol. 5, No. 1, 1983, 28–57; Caratini, “La rôle de la femme au Sahara occidental”, p. 98.

(13) María López Belloso, Irantzu Mendia Azkue, “Local Human Development in contexts of permanent crisis: Women’s experiences in the Western Sahara”, Jàmbá: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies, Vol. 2, No. 3, 2009, 159–176.

(14) Peter Erwig, Ausbildung in der Westsahara, Eine anthropologische Analyse zum Schnittfeld zwischen Alltagsorganisation im Flüchtlingslager, Unabhängigkeitskampf und Vorbereitung der Rückkehr, 2012, pp. 39–40; Tony Hodges, Western Sahara, The roots of a desert war, Westport, Connecticut, Lawrence Hill, 1983, p. 145.

(15) Pablo San Martín, Western Sahara, The refugee nation, Cardiff, University of Wales Press, 2010, 52; 53.

(16) Karl Rössel, Wind, Sand und (Mercedes-) Sterne, Westsahara, der vergessene Kampf für die Freiheit, Unkel/Rhein, Horlemann, 1991, p. 136; Tony Hodges, Western Sahara, The roots of a desert war, Westport, Connecticut, Lawrence Hill, 1983, p. 145.

(17) Frente Popular para la Liberación de Saguía el Hamra y Río de Oro; dt.: Volksfront zur Befreiung von Saguía el Hamra und Río de Oro; arab.: al-Ǧabha aš-šaʿbiyya li-taḥrīr as-Sāqiya al-Ḥamrāʾ wa-Wādī ḏ-Ḏahab.

(18) Pablo San Martín, “‘¡Estos locos cubarauis!’: the Hispanisation of Saharawi society (… after Spain)”, Journal of Transatlantic Studies, Vol. 7, No. 3, 2009, 249–263.

(19) Unión Nacional de la Juventud de Saguia el Hamra y Rió de Oro.

(20) Maja Zwick, “Translation matters, Zur Rolle von Übersetzer_innen in qualitativen Interviews in der Migrationsforschung”, in: Work in Progress. Work on Progress, Doktorand_innen-Jahrbuch 2013, Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung (eds), Hamburg, VSA-Verlag, 2013, p. 117.

(21) Alejandro García, Historias del Sáhara, El Mejor y el Peor de los Mundos, Los Libros de la Catarata, 2001, p. 120.

(22) See Jacob Mundy, “Neutrality or complicity? The United States and the 1975 Moroccan takeover of the Spanish Sahara”, The Journal of North African Studies, Vol. 11, No. 3, 2006, 275–306; Stephen Zunes, Jacob Mundy, Western Sahara, War, nationalism, and conflict irresolution, Syracuse, NY, Syracuse University Press, 2010, pp. 86–87. In the 1990s, Yasir Arafat attempted to dissuade Nelson Mandela, already President of South Africa at the time, from recognising the SADR; see Zunes, Mundy, Western Sahara, pp. 125–126.

(23) San Martín, ‘¡Estos locos cubarauis!’: the Hispanisation of Saharawi society (… after Spain), p. 252.

(24) Ernesto Gómez Abascal in Nicolás Muñoz, El Maestro Saharaui. Océanos de Exilio, 2011.

(25) José Antonio Monje, Solidaridad con nombre de isla y arena, Las lecciones del internacionalismo cubano en la RASD.

(26) Margaret Blunden, “South-south development cooperation, Cuba’s health programmes in Africa”, International Journal of Cuban Studies, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2008, 32–41.

(27) Francisco Martínez-Pérez, “Cuban Higher Education Scholarships for International Students: An Overview”, in: The capacity to share, A Study of Cuba’s International Cooperation in Educational Development, Anne Hickling-Hudson, Jorge Corona Gonzalez and Rosemary A. Preston (eds.), New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, p. 75.

(28) San Martín, Western Sahara, p. 148.

(29) Ibidem. See also ACN, En el trigésimo aniversario de la independencia del Sahara Occidental, Más de dos mil jóvenes saharauis recibieron en Cuba estudios universitarios superiores.

(30) Elena Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, “Education, migration and internationalism: situating Muslim Middle Eastern and North African students in Cuba”, The Journal of North African Studies, Vol. 15, No. 2, 2010, 137–155.

(31) Maja Zwick, Emplacement im Kontext der saharauischen Flüchtlingslager in Algerien, Zum Verhältnis von Orten und Zugehörigkeit unter den Bedingungen von Flucht, Migration und Rückkehr, 2024, p. 192.

(32) Liman Boicha, “Las estaciones de nuestro exilio”, unpublished, 2007; as cited in San Martín, Western Sahara, pp. 148–149.

(33) Fernando Ortiz, Cuban Counterparts, Tobacco and Sugar, Durham, London, Duke University Press, 1995; Fernando Ortiz, “The human factors of cubanidad, Translated from the Spanish by João Felipe Gonçalves and Gregory Duff Morton”, HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, Vol. 4, No. 3, 2014, 455–480.

(34) Marianne Holm Pedersen, Between Homes: post-war return, emplacement and the negotiation of belonging in Lebanon, Geneva, 2003, p. 5.

(35) Zwick, Emplacement im Kontext der saharauischen Flüchtlingslager in Algerien, p. 182.

(36) San Martín, Western Sahara, p. 151.

(37) Ibid., p. 147; Judit Tavakoli, Zwischen Zelten und Häusern, Die Bedeutung materieller Ressourcen für den Wandel von Identitätskonzepten saharauischer Flüchtlinge in Algerien, Berlin, regiospectra, 2015, p. 112.

(38) Homi K. Bhabha, The location of culture, London, Routledge, 1994.

(39) Carmen Gómez Martín, La migración saharaui en España, Estrategias de visibilidad en el tercer tiempo del exilio, Saarbrücken, Editorial Académica Español, 2011, p. 55.

(40) Association Sahraouie des Victimes des Violations Grave de Droits de l’Homme Commises par l’Etat du Maroc, Sahrawi youths and human rights defender lost at sea, New tragedy in Western Sahara: Death of numerous young Sahrawsi, among them, militant and human rights defender Naji Mohamed Salem Boukhatem, El-Ayoune – Moroccan occupied Western Sahara, 27.11.2006. See also: Gómez Martín, Carmen, La migración saharaui en España: Estrategias de visibilidad en el tercer tiempo del exilio. Saarbrücken, Editorial Académica Español, 2011, pp.55-56.

(41) Gómez Martín, La migración saharaui en España, p. 52

(42) Liman Boicha, “New Saharawi Poetry: A Brief Anthology”, Review of African Political Economy, Vol. 33, No. 108, 2006, 333–335.

(43) Jennifer M. Murphy, Sidi M. Omar, “Aesthetics of Resistance in Western Sahara”, Peace Review, Vol. 25, No. 3, 2013, 349–358.

(44) Jacob Mundy, Western Sahara Between Autonomy and Intifada; Stephen Zunes, Jacob Mundy, “Introduction: The imperative of Western Saharan cultural resistance”, in: Settled wanderers, Sam Berkson and Mohamed Sulaiman (eds.), London, Influx Press, 2015, pp. 11–12.

(45) San Martín, Western Sahara, p. 141; Zunes, Mundy, “Introduction: The imperative of Western Saharan cultural resistance”, p. 22.