After reading Tajimara

Rodolfo Lara Mendoza is a Colombian writer. He has published the book of short stories La gravedad de los amantes (Editorial UIS, 2016; Cero Squema Editores, 2022) and the poetry books Esquina de días contados (Pluma de Mompox 2003), Y pensar que aún nos falta esperar el invierno (Pluma de Mompox 2011) and Alguna vez, algún lugar (Turpin Editores, 2018), the latter included in the collection Palabra de Johnnie Walker, published in Spain.

I do not know what convoluted route has led me from a story by García Ponce to an old episode I thought forgotten, nor what importance it may have today. There are roads that begin in books and end in life, although as a rule it happens the other way around.

The story is titled "Tajimara", and it is perhaps because it is narrated from inside a car, that reading it has taken me back in time. I could see myself again, a silent child, sitting in the bus which took me to school, a neighbour at the wheel. It was a yellow bus, meant for the transportation of state employees. One rainy morning, I saw from one of its seats the same "fir trees shaken by the wind, the brown mountains and the grey, washed-out sky" that the narrator of "Tajimara" sees. Although in my city there are no fir trees, and instead of mountains it has only a small hill whose green fades as the dry weather progresses.

It was the 1980s. I lived in a suburban neighbourhood, on a street with nineteen tiny houses. Not so tiny were the souls that inhabited them - I could name them one by one and do them justice in the face of time's relentless obliteration. I could put my hands in that factory of oblivion in a brave attempt to save them from death. To recreate their lives, to relive their loves.... Isn't that what literature is for?

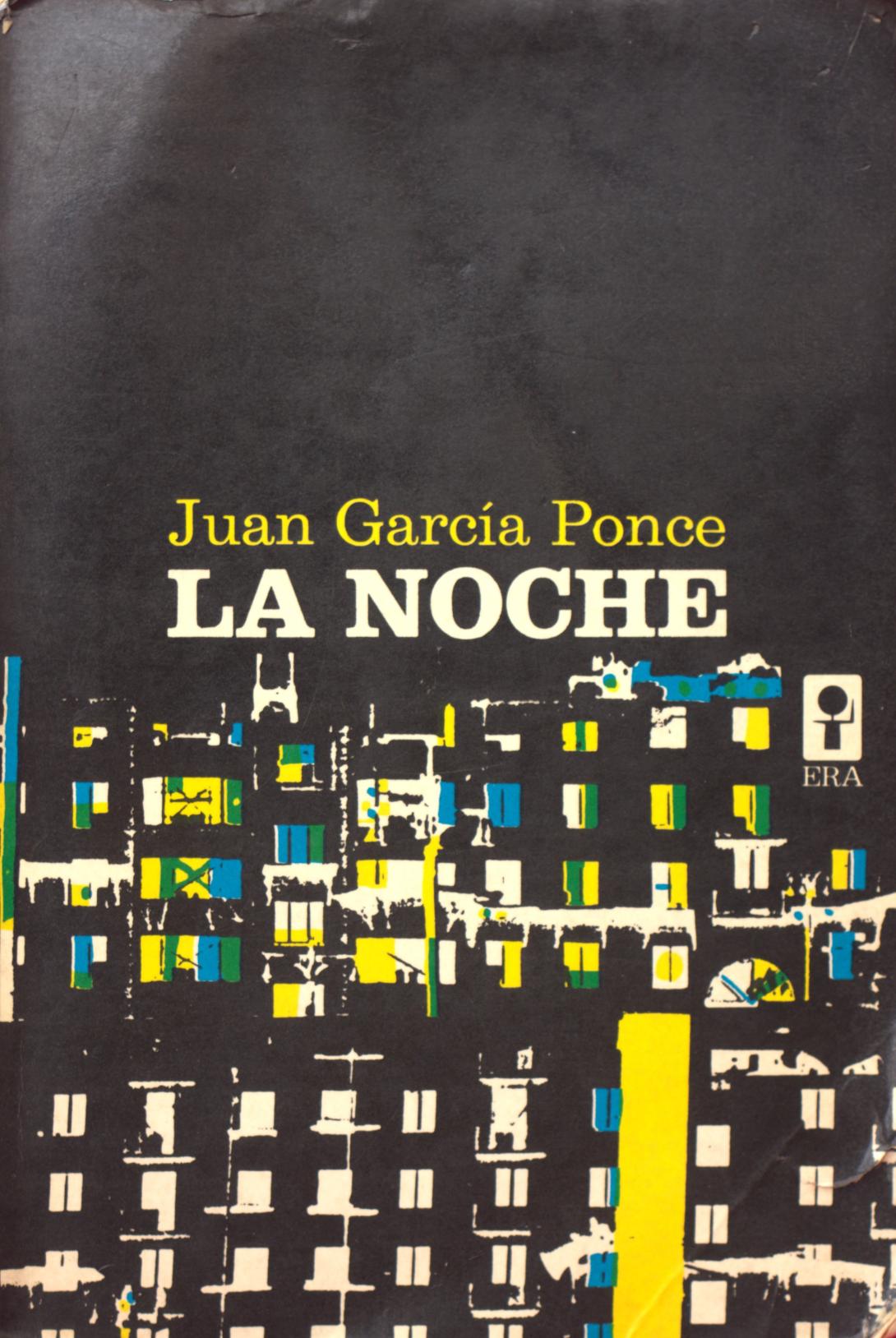

ERA

ERAJuan García Ponce | La Noche | ERA | 87 pages | 6.56 USD

Included in a 1963 volume of short stories entitled La noche, "Tajimara" depicts the love-hate relationship between the narrator and Cecilia, their meetings and misunderstandings, and the "eternal stupid game" he lent himself to: "a masochistic egotist who had found the perfect partner." Line after line, an inventory of wounds is presented. On a rainy afternoon, while being driven by Cecilia to a party in a town outside Mexico City called Tajimara, the narrator recalls the times he made the trip with her to the workshop of Julia and Carlos, a sibling couple seemingly engaged in incest. Listening to Cecilia hold forth, the narrator recalls the years when he was lost in love with her, and those times when he thought he had forgotten her, only for her to appear again, ready to reignite his feelings:

Before, Cecilia and I had driven these same twenty kilometres countless times; but the landscape had never seemed so melancholy to me as it does now. In a sense, her driving was always almost symbolic. I had been guided to where she wanted all my life, and when after six months of not seeing her she suddenly showed up to invite me to Tajimara again, I didn't even have time to think about how I felt, I simply accepted, aware that I would never know if I loved her or hated her.

Four years after the publication of "Tajimara", in 1967, García Ponce was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. His life began to hang by a thread. Little by little he lost his motor skills. His voice, until then fluid, became slower until it was dark, clumsy, disjointed. Just like his voice, I write this: a story that wants to move forward but flounders in the gaps of my memory.

I don't know if I took that bus during my six years of high school, between '85 and '90. I should have taken it: there was a shortage and the neighbour didn't charge me. Terrible things happened in my country during those years. The eruption of the Nevado del Ruiz volcano. The seizure of the Palace of Justice. The assassination of the director of El Espectador: Guillermo Cano. The Villatina tragedy. The car bomb attack on the DAS building. The assassination of presidential candidates Bernardo Jaramillo Ossa, Luis Carlos Galán and Carlos Pizarro Leongómez. And amidst all this, the return of my father.

It was terrible, the way I reacted to that event. He had left the city after breaking up with my mother and one day he came back to visit us. Knowing this, I hid in the yard. I stayed hidden among my chickens for a long time. There was something of García Ponce in that gesture. When asked why he always wore black, he would answer quoting a Chekhov character: "Because I am in mourning for my life". I always wore colours and in my only monochrome stage I was inclined to wear white. But mourning, like the procession, goes within. "Behind every sin there is a sinner who hides in the shadows and never shows his face." Something extremely fragile had been broken at that moment: the trust and love I had for my father. I would come to know it later, when others also lost the trust and love they felt for me and I could see myself, lost on the same drunken path where he himself had become lost.

The first bus announcement came at five o'clock: after topping up the radiator with water, the neighbour would rattle the hood in the silence of early morning. We would just be getting dressed, or even still asleep, dreaming, and be forced to run. We would leave on the bus earlier than any other children. In the first months of the year, with the streets still dark, and already towards the month of May with the sun beating on our faces. I use the plural because I was in the company of other children. Two childhood friends. El Negro, who attended the same school as me, and Puya, who went to a different one. We would drive past our school before six o'clock, cross the city from end to end and only an hour later, when Puya was gone and we were on our way back, El Negro and I would get off, just in time for the school gates opening.

One morning, the neighbour pulled my mother aside. He explained to her that one of the female passengers had complained about using the vehicle as a school bus and as a result, he would have to drop me off on the way, so the woman wouldn't see me. My friends were not affected: El Negro was the neighbour's son, and Puya got off a little before the woman got on. It must have seemed an injustice to me. That someone who didn't know me would put me down... Something similar happened to the character of "Tajimara". On a whim, Cecilia would take him on and off the bus of his feelings:

The endless afternoons when I tried to please her and the mingled smell of our bodies after talking for hours on end in bed with our legs intertwined, staining the sheets with ash. "Sometimes I don't feel anything. It's no use. It's always been the same for me. I'm sick." Always with whom? But then, with her sweat rolling, she would wrap her legs around my waist and I would search for her inside and after tossing and turning and moaning and sighing she would finally loosen up and murmur "thank you, thank you for waiting for me" (...) Then she would spend the whole day with me. I never tired of looking at her. "You, you". "No; I am no longer that one. Don't dream, don't invent. It's all over."

Cecilia loved only herself, but he didn't notice. Or maybe he did. Love and self-deception travel on the same bus, obliged to sit together. Not for nothing does the narrator say: "We compose everything with our imagination and we are incapable of simply experiencing reality."

I remember the neighbour as an honest man, of iron moral principles. Extremely rigorous and reserved, given the festive atmosphere of our neighbourhood. He could well have decided not to take me, but for some reason he chose to be permissive. Maybe he saw in me something of his son or maybe he was haunted by some ghost: that of having launched a petition, years ago, calling for us to leave the neighbourhood, after my mother separated from my father and moved in with another man.

The fact is that from that day on, the waiting began. From that hour still in twilight when the bus left me in front of the school. From that hour when I sat on a parapet counting the minutes until the caretaker opened the gate. The waiting and the loneliness in that street where nobody passed, or the few who did were still bathed in the water of sleep. People who barely said hello, leaving no room for the slightest conversation. Then I would have liked to read "Tajimara". To meet Cecilia, the woman in the story. Capricious like no other, ridiculous to the point of exhaustion, "fragile, absurd, shy and shameless... so difficult to penetrate and so unbalanced, and sometimes also so silly". The same one who had me taken off the bus, I know now, brought to my reality of those years by a strange loop in time. Only then can I understand what she was like, who she was, and what she had against me. For I never knew her name and her face I have forgotten. Perhaps I never saw her, absorbed as I was with what, by way of discovery, was offered to me outside: the morning chaos of my first city and, a little later, its gift of loneliness: the wait in front of the still-closed school, and that feeling of desolation so similar to when a love is lost.