in the deep mud

Galant Lies: the poetry column under the direction of Alexandru Bulucz - loosely based on Johann Christian Günther, the baroque poet on the threshold of the Enlightenment, who mocked poets with the words that they were „only gallant liars“. Poetry will be reflected on and presented here: in reviews, essays, monthly poems and occasionally also lists of best poems.

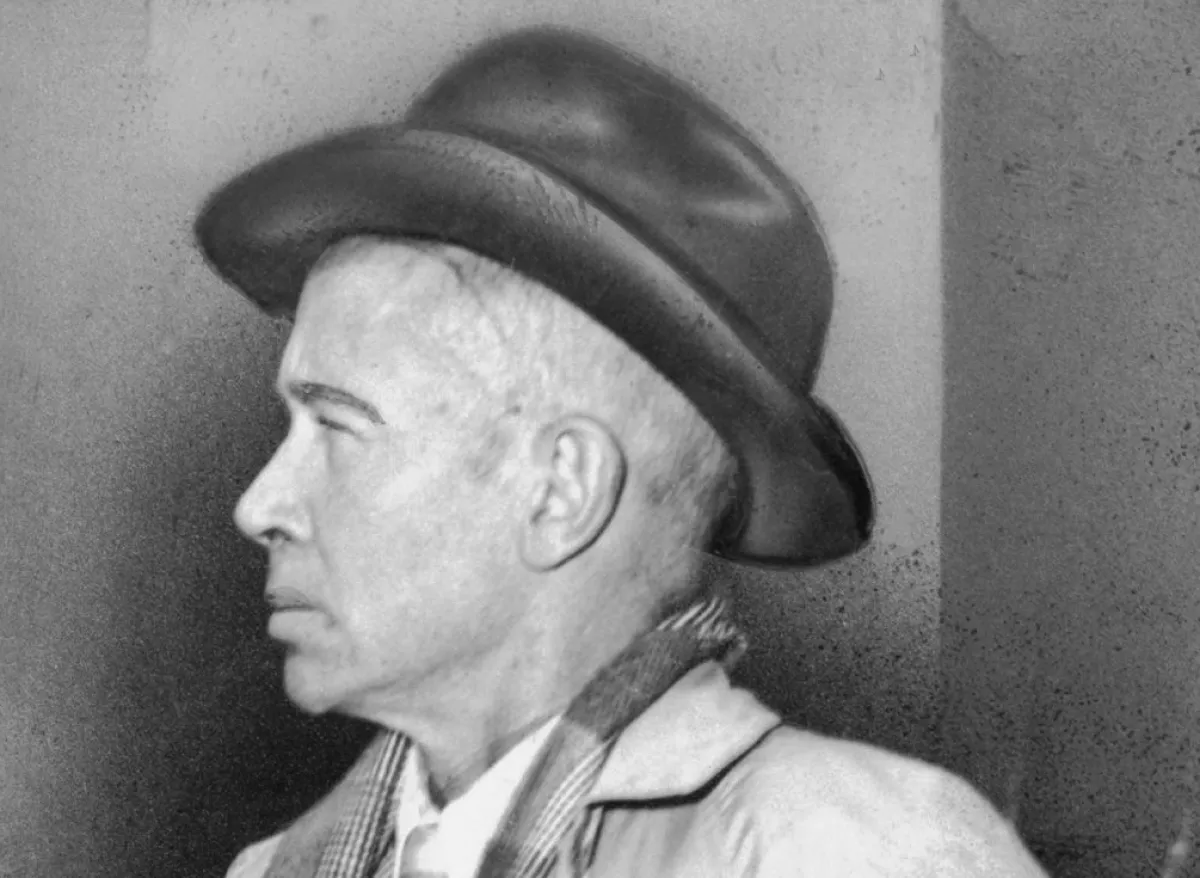

Edward Estlin, or E. E. Cummings, was 32 when he published his second volume of poetry, is 5, in 1926. His war experiences of 1917 as a volunteer in a medical corps in France were still fresh at this time. He and William Slater Brown were held for several months in a military prison camp in Normandy. The two young American writers, who had met and become friends on the ship to France, tended to stay among the French soldiers and spoke out against the war. Their letters home seemed suspicious to the military censor. After all, they had been accused of espionage by the French military. Cummings was allowed to return to the United States for Christmas 1917 largely thanks to his father, who had campaigned for this.

The poem my sweet old etcetera, part of is 5, was also influenced by the First World War. It was included in the large bilingual edition of Cumming's work in the GDR, so klein wie die welt und so groß wie allein, which was published in 1980 in the famous "Weiße Reihe" of "Volk und Welt". In his afterword, editor Klaus-Dieter Sommer portrays Cummings as an anti-American, anti-bourgeois poet. To justify his publication in East Germany, he ignores the other dimensions of Cummings, which had been emphasised in West Germany from the 1950s onwards, when it was just as ideologically important to portray him as an anti-communist poet. The fact that some of the same translated poems were presented from these two perspectives only underlines how difficult it is to ideologically define Cummings.

The preface can be found in the original on the pages of the e.e. cummings free poetry archive.

Adding to the difficulty is the fact that he delivers his poems less on a level of content than on that of grammatical and typographical experimentation, performing one burlesque after another with the language elements until the content, even in his ideological message, disappears behind the form. In the foreword to is 5, Cummings defines his "theory of technique" from the viewpoint of a "burlesque comedian", "who is exceedingly fond of that precision which produces movement", and who is not obsessed with things made, but with the making of things: "My 'poems'", he writes, "compete with roses and locomotives", as well as "with each other and with elephants and with El Greco".

The modernist style of the poem my sweet old etcetera is obvious. The greeting suggests a letter, most likely to the loved one, who is also addressed erotically in the parenthesis of the last stanza; the sparse, idiosyncratic punctuation, the repeated omission of the space, the contrast between upper and lower case and the inconsistent repetition of the Latin expression "et cetera" - all this adds up to a supposedly misplaced orthography that snatches the poetic expression from the sphere of bourgeois linguistic convention. What could be interpreted as a careless error suggests that the letter was written in a hurry or in a stressful situation, "in deep mud" perhaps even a battle scene; there was no time for stylistic smoothing; the message took precedence over the form of the message.

The narrator repeats the "et cetera" eight times, and each time the phrase has a different meaning. Twice it is split up by the line break, and once it is capitalized, thereby garnering particular depth. The person addressed in the letter, as well as the reader, completes the enumeration initiated by the narrator with each mention of "et cetera", deducing this from what comes before. Explaining it was unimportant or too time-consuming for the narrator.

In addition to the person addressed, the narrator's aunt, sister, father and mother also appear. Only the sister comes off well - her war contribution was the production, the 'making' in Cummings' sense, of countless practical items of clothing. The fact that "my sweet old etcetera" is also a poem dedicated to the sister becomes clear in the third verse, the suspended two-liner "for,/ my sister". The father, mother and aunt, on the other hand, only utter generalities typical of the era, which the narrator (son/nephew) interrupts, cutting short with "et cetera": the aunt knows about the higher meaning of war, the mother hopes for a heroic death of the son, and the father talks himself hoarse when he muses about the honour the soldier, whom he would have liked to be if he had been able, patriotically fights for in the war.

And because the narrator is dreaming and delirious about the loved one, it is a letter that, like Kafka's "Letter to the Father", is staged as a document that was never sent. This is further suggested by the poem's leap from past to present tense: Father, mother and aunt had uttered platitudes at the time, during the war, but the son and nephew is now, at the moment of his letter-writing/dreaming, "in the deep mud".

Is my sweet old etcetera an anti-war poem? Not necessarily! Rather, it brings the soldier's reality of war into collision with the couch commentary, that gratuitous idealization of war by those at a safe distance.

+++

my sweet old etcetera

aunt lucy during the recent

war could and what

is more did tell you just

what everybody was fighting

for,

my sister

isabel created hundreds

(and

hundreds)of socks not to

mentions shirts fleaproof earwarmers

etcetera wristers etcetera,my

mother hoped that

i would die etcetera

bravely of course my father used

to become hoarse talking about how it was

a privilege and if only he

could meanwhile my

self etcetera lay quietly

in the deep mud et

cetera

(dreaming,

et

cetera,of

your smile

eyes knees and of your Etcetera)