What I don't seek, I find

Poetenladen

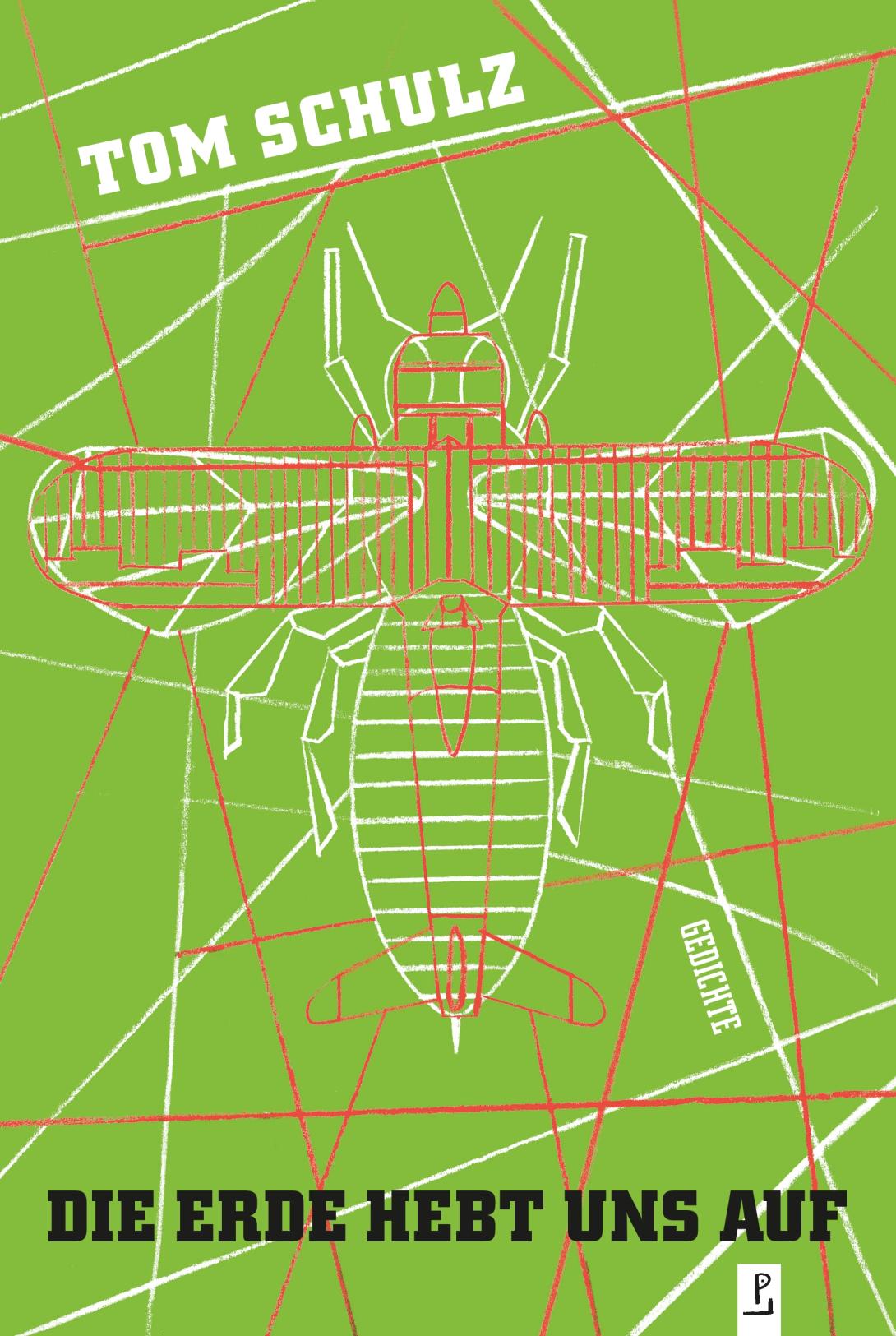

PoetenladenTom Schulz | Die Erde hebt uns auf | Poetenladen | 72 Seiten | 19.80 EUR

"The earth lifts us up. Where we lay/ left, where we were abandoned. There, is space/ to dig, and the thread of happiness holds." Tom Schulz comes to this conclusion in his poetry collection Die Erde hebt uns auf (The earth lifts us up), published by "Poetenladen" in Leipzig. But where the feeling of happiness ends, an awareness of the critical state of our habitat re-emerges, and the poem becomes political, a critique of destructive capitalism.

One of the key concepts of the philosopher and deconstructionist Jacques Derrida is "destinerrance". This French amalgamation of "destin", "destination" and "errance" - meaning "destiny", "destination" and "odyssey" or "wandering" - is a paradoxical spatial and temporal figure of speech that can best be translated as "erroneous fate". Anyone writing literature is embarking on a subjective quest, searching for something ill-defined, namely chance.

For the poet Tom Schulz, too, wandering is a central motif. "What I don't seek, I find", he writes in his new volume of poetry Die Erde hebt uns auf: "soweit ich irre, gibt es den/ Weg, mich findet wieder Hang, Wein und Senke" (unless I'm mistaken, there is the/ way, I find the slope, vine and hollow again).

The terrain explored in the first cycle of the book is in Italy, on the Adriatic. The gardens with their flora and fauna, through which the reader wanders, still resemble a paradise of sorts. Finally, language itself is found: "Poetry, delicious fermenting apples". For there is text in every body:

Then

we climb the ladder, above us leaves and pears (not

stars), shared with the wasps. In each body

a text that says: leave me unfinished, open to all

sides -. We read in the book of the night with our

hands: the ant writing, clearly decipherable.

Tom Schulz teaches us to see perfection in what is incomplete and open on all sides, without ignoring the danger that man has exposed creation to. God exists, but he has become almost meaningless, reduced to the size of a pea; the Risen One, who once squatted among seasonal workers, has been lost; and the figure of St. Mary is as plastic as the beach chairs on the Adriatic or the pipe on which a woodpecker taps.

Thus Tom Schulz merges his description of nature as becoming one with the landscape, his criticism of capitalist environmental destruction and his apocalyptic vision of an impending explosion tearing apart "the angry narratives" towards which we stagger in a carnival mood.

From the development of agriculture, when agricultural work symbolised the marriage of the god of heaven to the goddess of earth, to the senseless exploitation of nature by corporations that have taken the place of the gods - this is the bitter evolution that Tom Schulz shows us:

The earth becomes the owner of our companies.

What we take from it, what we grow, we no longer sacrifice to the gods. Corporations are no

stars, profit zones are dwindling.

[...]

Who exchanges shares, who pumps

back what has been siphoned off? ... Already

geckos are moving into the hall with the masterpieces.

A shovel of sand to crown us.

And the animals reach the supermarket ark.

The portrait poems of the second cycle, in which Tom Schulz places the subjects in specific locations, are also accompanied by social criticism. In the poem about Hans Arp, this is evident in the reference to "well-furnished suede handbags".

However, the portrait poems, which bear witness to an extensive reading biography, become particularly interesting when they enable a political identity connection to the author Tom Schulz. The poems about "Bobrowski in Friedrichshagen", the "Volksarmisten in Tautenheim", "Johnson bei Travemünde" or "Hilbig in Edenkoben" remind us that Tom Schulz also has an East German background. He was born in 1970 in Großröhrsdorf, Saxony, and grew up in East Berlin. These texts also speak of an East as an "approach in ashes, happened, done/ committed, forgotten"; of "old concrete fields" and "asbestosis"; of a "home child/ among informers" and "border fences"; finally of a "worker/ with two left hands".

The third and final cycle of the book is distinguished by its humour. It is a satire on our times The ancient Roman poet Ovid, whose Metamorphoses are still read today, is sent among the moderns - much less mythically exaggerated than in Christoph Ransmayr and his ghost story The Last World. As a media critic, he is read in Vogue, Zeit or Kronen Zeitung. In Austria, he shouts after "the undead Jörg Haider" that he should sneak away. As a love poet, he criticizes progressive gender politics. He reflects on the existence of poetry as a shopkeeper and in the context of social media. His polemical attacks continue to the end.

With the formality, beauty and melancholy of the first cycle, the political rigour of the second and the belligerence of the third, Tom Schulz has published an outstanding volume of poetry.