A touching nostalgia

Poetenladen

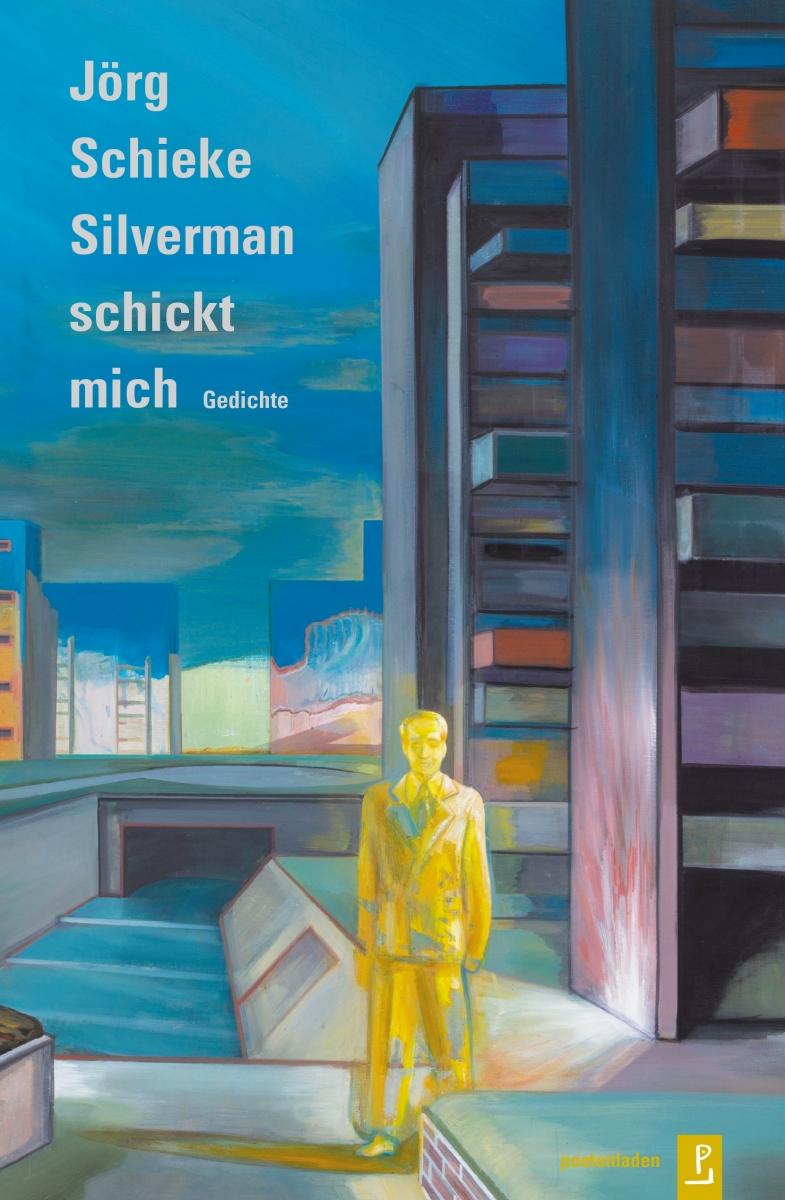

PoetenladenJörg Schieke | Silverman sends me | Poetenladen | 88 Seiten | 19,80 EUR

Silverman - a name with Yiddish origins - is still common today. Author Jörg Schieke does not reveal much about the eponymous protagonist in his new volume of poetry. We learn of a son called "Silverman junior", of Silverman's affinity for culture and that he is a good boss keen to manage his own appointments.

The narrator - Silverman's employee and delegate, in whom he even holds a share - is the man for the hard graft, the organiser. He, who describes himself as "the great middle-man", does the press work, the booking and recordings, feeds the animals and occasionally does security duty. We can only guess what kind of work that might be. However, there are clearly shades of animal ethics and social criticism. Violence against animals and property is denounced, as is a so-called " age of sweeping". The narrator makes this latter point about Silverman's cultural program, which includes visits to "Europe's zoos, Thailand's cuisine and Brecht's Brahms".

The search for further characteristics of Silverman proves futile, even where the metal silver, which gives him his name, plays a role - as in the poem "Silver in February", which offers a surprising explanation of loneliness:

The word

loneliness means the relationship of people

to the obligatory, the notorious

disappearance of time.

Jörg Schieke was born in Rostock in 1965 and grew up in Stralsund. He studied at the German Literature Institute in Leipzig, during which time he was also editor of the literary magazine EDIT, and has worked as a radio journalist for twenty years, primarily for MDR. "Silverman schickt mich" is his fourth volume of poetry.

The skillful use of omission and thought-provoking riddles is an effective device in these three cycles of Jörg Schieke's poetry collection. The charm of his poems lies in the fact that they cannot be fully deciphered. What does the 'staircase butterfly', a former paymaster and steelworker, represent in "Flügelldings"? Is it a symbol of the memory of his time in the military and a career path specific to the GDR?

This address is inactive, destructive, and it belongs

to you. The staircase butterfly (ex-paymaster) scratches

at the door. It lives with the scarves, in the lost property

box, and when something moves in there, it flutters open.Your address is inactive, depressive. The staircase butterfly (ex-

steelworker) scratches at the door. It

lives with the scarves, in the lost property box, and

when something moves in there, it flies to you.

In the lost property box, Jörg Schieke also finds language. At one point, someone is sent home "zum Kulpen" - "kulpen" is a Low German variant of "to sleep". And so the spatial and temporal setting of the poems can be ascertained . Wolgast, Laage, Binz, the Baltic Sea - we are dealing with the North German region. There are also certain references to the time: for example, the Walkman, which came onto the market in 1979 and became a status symbol for young people in the 80s, the emblem of their new way of life. Typical Eastern words such as "Plast" and "Plaste", which have been disappearing since reunification, indicate that this space-time also has a political dimension.

Poems from the first cycle serve as a prelude to the second. There, the career choice has not yet been made, but is already being courted. In Rostock they are looking for a teacher, in Laage for a locksmith, in Wolgast it is the federal government that is offering jobs. "Many professions burn out in the local heat, regardless of location" it says at one point.

In the second cycle, the question of profession is then resolved. You find yourself as the "only high school graduate/ among all the antichrists":

Stationed

in the electro-agrarian Thuringian Forest, behind the

two-meter fence with the sprinklers.

Sprutzen was the name given to the soldiers in basic training in the NVA, which was also very hierarchical in terms of comradeship.

This is an autobiographical story about the sprutzen "Schiecki" and how he is treated by his seniors, the so-called "Lädies" - a word invented by the author. Jörg Schieke seems to be saying that the 'Sprutzen' were treated as a jack of all trades by the Lädies, (hints of the english 'ladies'), according to the idiom "girl friday"

The leftovers flew all

day, floating like fluff

through space. Whereupon again -

Schiecki, finally bind the apple grits

tight. Slits in the silver paper, holes to breathefor my dear vitamins.

Which brings us from the good boss Silverman to the Lädies, in whose service the Sprutze has to endure some unpleasant things. The discourse on work, which runs like a thread through the volume of poems, is permeated with a touching nostalgia, with words such as "Heimgang", "Nieheimgepäck" or "Nieheimbriefe", as well as the desire to be "cured of everything reminiscent of home" and preferably liberated.

A systematic poetic examination of the NVA was long overdue. Jörg Schieke has mastered it brilliantly, with this demonstration of his command of poetic language. When he writes of a "scale of obscurities", heshows a fine sensitivity to his own poetic style. When he reflects on the consequences of a misspelling in the last poem of the volume, you turn back and once again enjoy the clever word play that rhymes "Kontinente" with "Harry Bolafente" (sic!)