The present as past

Plaion Pictures / Studiocanal

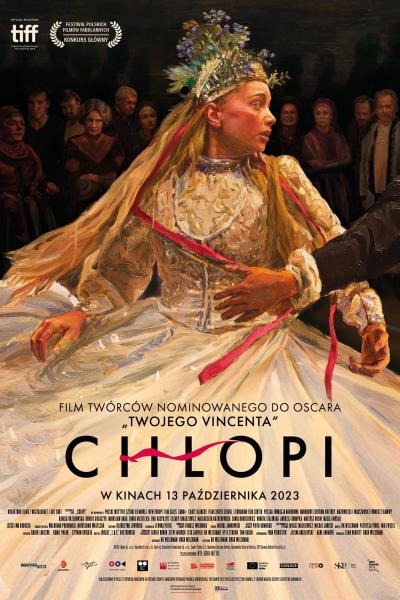

Plaion Pictures / StudiocanalThe Peasants | Dorota Kobiela & Hugh Welchman | 115 minutes | Poland 2023

"The snow fell straight to earth as if through a fine sieve, it fell evenly, monotonously and silently, covering roofs, trees and hedges, like a bleached fabric, blanketing the whole earth in its soft down."

- W.G. Reymont, The Polish Peasants, Volume 1 (Autumn)

Władysław Reymont's 1902-1908 epic, published in serialised form, is one of the great novels of the early 20th century, for which the author won the Nobel Prize in 1924, rightly outshining the also nominated Thomas Mann. Rereading this almost forgotten novel, which is over 1,000 pages long and divided into four seasons, one is surprised not only by its exceptional linguistic quality and razor-sharp ethnographic inventory of rural life, but more than anything, Reymont's almost overwhelming relevance today.

Reymont uses the stylistic devices of both realism and literary naturalism, choosing an unusual narrative path with his portrait of peasant life in an imagined Polish state at the end of the 19th century. On the one hand is the father and son story between the richest farmer in the area, Matheus Boryna, and his son Antek. Their relationship becomes a dysfunctional nightmare when both fall in love with the same woman, the young, self-confident Jagna Paczesiówna. She conforms to local custom and marries the much older father, but does not stop following her passions. However, these passions of a modern woman do not only consist of longing for Antek. As with Theodor Fontane and his Effi Briest, Reymont is careful not to pass moral judgement on his heroes, but to show them as part of an outdated system. Their actions are time-honoured and supposedly strengthen the small community. Nevertheless, all involved sense that times are changing and Jagna is not alone in her undefined yet pulsating search for her own longing and a new identity. A search in which physical lust and its significance are thematised in an extremely modern way.

While this is the narrative hook, Reymont primarily tells the story of a village shortly after the abolition of serfdom has released its inhabitants from their previous isolation from the world. He tells of hierarchies between rich and poor, of vicious, passionate and tender human relationships, of unimaginable famine, of amoral nobility and of merciless investors from abroad who, by buying up land, threaten to deprive the villagers of their means of subsistence.

From today's perspective, these neoliberal conditions are so easily transferable to the current situation in the global South that Reymont's great novel connects with your heart and soul simply for its universal foresight - a modern film adaptation was indeed long overdue.

However, the novel's length and its ambiguous, complex plot already calls for either an overlong cinematic epic or even a series of films, to do Reymont any justice. Or taking the risk, as Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman have done, of selecting a representative excerpt to give an understanding of what this novel could still mean today.

In The Peasants, Kobiela and Welchman opt for the simplest and perhaps most predictable form, the triangular story between father, son and wife. In the novel, this also functions as the driving force of the social universe and which, as already mentioned, can also be seen from today's perspective as early feminist empowerment of a woman living in a patriarchal society. Kobiela and Welchman stick closely to the book's dialogue and action, the four seasons are accurately integrated, as are the festivals and music, and although societal rules for women, at that time sold practically like cattle into marriage, are also placed centrally, there is room occasionally for feelings and moments of reflection.

As in their last film Loving Vincent (2017) about the death of Vincent van Gogh, the pair of directors transform The Peasants into an artistically sophisticated meta-format. Initially filmed with actors, the sequences were then animated. In Loving Vincent, these animations were in the style of van Gogh; in The Peasants, it is the painting of contemporary Polish painters of the late 19th century, whose style is not only adapted but also accentuated by the embedding of several paintings by artists such as Józef Chełmoński, Ferdynand Ruszczyc and Leon Wyczółkowski. These elaborate, artistic animations, the result of over 200,000 hours of work, give the film a constantly surreal, almost psychedelic character that is impressive and unique.

At the same time, however, this approach also robs Reymont's story and its characters of their narrative intensity, their suffering and passion. The bitter poverty, alluded to in passing, dissolves into shimmering, artistic delight, as does the story of love and suffering of the three protagonists, and of Jagna in particular. It is true that transitional moments in their lives - the cabbage festival, the wedding, the seasons - become, with just a few brushstrokes, impressive symbols of a simple life. But feelings and emotions, always central to Reymont's work, are notable for their absence .

While the film adaptation reserves the right not to make moral judgements, this often seems contrived and understated, particularly so in the cruel final scene, which recalls Nikos Kazantzakis' Alexis Sorbas and the film adaptation by Michael Cacoyannis.Because of course, the envy and the resentment that come with living in constant economic (and political) uncertainty are not simply a reaction to a young woman’s empowerment and her strong feelings. Rather, it is society as a whole that is relevant and makes people who they were then and are still today, in very similar economic and political circumstances. Frustratingly, this aspect has been omitted from the film adaptation - a real shame, because what remains is nothing more than the skeleton of this dense literary masterpiece.

However, if you can’t remember or are not familiar with the original, Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman's ambitious film adaptation is thoroughly convincing; the way in which the animations first accompany the narrative framework of early female empowerment, then propel it towards the bleak dénoument, is almost language become film and a moment that is as intoxicating as it is illuminating.