Ruthless accuracy

Reading is such an incredibly subjective process. So much plays into it. How you feel about the author. What you know about him. What you have already experienced with them. Whether what you read opens a door in your own memory or experience. And so on. If you have seen Edgar Selge as a theater actor, how he can bring wit and originality to any role, then that also means that you are willing to give this book a large advance of sympathy. It carries for at least 50 pages, by which time a genuine interest must have formed.

After the dedication "For my brothers", a cryptic King Lear quote follows, but then it's straight into medias res: House concert at the Selge home, with 80 prisoners from a juvenile detention center.

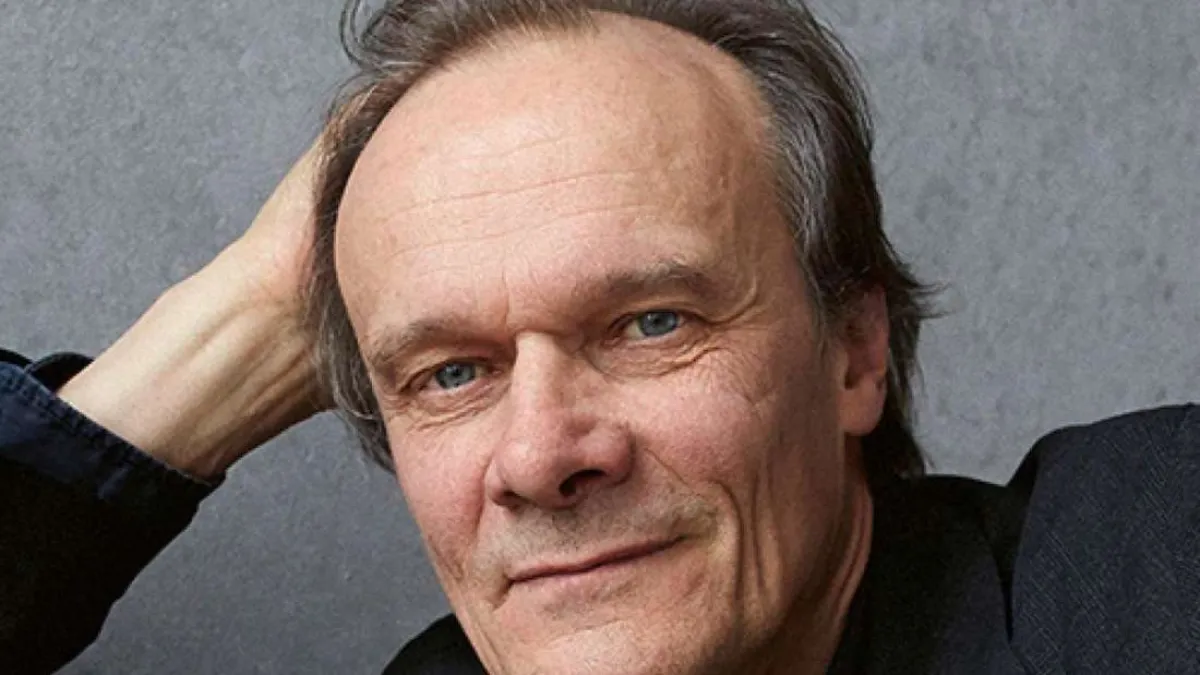

Edgar Selge | Hast du uns endlich gefunden

Rowohlt Verlag | 300 pages | 24 euros

Edgar Selge tells the story from the child's perspective, from the son's perspective. Music is a narrative and thematic leitmotif, everyone in the family plays instruments, Mozart and Beethoven are household saints. The father is an excellent pianist, the brother Werner becomes a professional cellist. The extraordinary thing about his childhood: Edgar Selge's father, a senior government councillor who plays in this house concert himself, is the director of a juvenile detention center and because everything that children experience is normal for them, it is for Edgar too. Somehow this immediately brings to mind Joachim Meyerhoff and his youth on a psychiatric ward ("When will things finally return to the way they never were"), his father also a director. Unusual circumstances of a childhood, episodic storytelling. Meyerhoff calls his book of memories a novel and thus immediately admits what is actually self-evident: the narrative about one's own childhood must fill in gaps, must invent dialogues, paint details. Admitting a lack of objectivity makes sense and is consistent. Karl Ove Knausgård did the same with his six-volume mammoth novel autobiography, "Min Kamp" in Norwegian. As a reader, you usually forget that, at least when you're captivated.

The fascinating thing about childhood memories is the attempt to take us back into the mind of a child, into the world of a child. Selge seems to do a great job of this, in any case he makes his remembered experiences resonate and sing. The continuous present tense helps, you slip into his head and sit at the family table. But just as he occasionally jumps into the future of the adult and thus leaves the childhood building, some sentences are also wiser than the experiencing child. This is not a pity, because otherwise the reader would miss out on crystal-clear analyses or later insights. For example, he writes about his parents' opinions: "But I have to turn their views around so that I can come to my own." A sentence with universal validity. It is an essential part of any emancipation process from one's parents to fight for the right to interpret the things in life. Older siblings can be very helpful in this process, in Selge's case his brothers Werner and Martin, who get into heated arguments with their father when it comes to his anti-Semitic theories or his repression of Nazi atrocities. The young Edgar's secret visits to the cinema are also part of his dissociation from his parents and their doctrinaire, national-conservative cultural tastes, with which he fights for a world outside the family in which he can be part of the current popular cultural scene. Just as he can immerse himself in worlds of battle and war in the garden of the house thanks to his strong imagination, he escapes into the adventure worlds of classic films at the movies and gains James Dean as a big brother and role model. His experiences at school, his first love and his conversations with juvenile delinquents also allow him to broaden his horizons. But the focus of the narrative remains the family.

Although the educated and highly musical father regularly beats little Edgar and terrorizes him with his demands, he cannot help but love him and look up to him. This, too, is a fate of universal truth and the drama of countless tormented children. The reader has to endure the child's repressed rage, which he cannot feel, making it emotionally exhausting to read at times. However, the emotional tension then breaks out in seemingly completely incomprehensible actions. Edgar steals, lies, tricks, destroys sympathy, disappoints and provokes, making your hair stand on end as you read.

The ruthlessness and accuracy with which the author describes the child's complex and often ambivalent emotional state is breathtaking. Like all great literature, it offers the opportunity to illuminate one's own inner world down to the deepest chambers by comparing or understanding, as it were, together. How did I become who I am?

The book describes the generation between the world wars from the perspective of a child born in 1948. The father lost two brothers in the First World War. At the end of the Second World War, the parents fled Königsberg for the West, still very upper middle-class in character, but with deep roots in National Socialism. They were unfamiliar with democratic post-war Germany, preferring to be completely absorbed and isolated in music. The older brothers are against it, demand a confrontation with the Nazi era, but allow themselves truces while making music together; the younger Edgar is confused, suffering, loving, observing, tactical, still completely caught up in the world of war. He wants to understand his parents, he loves them. He works his way through them. There is the following sentence about his father: "He doesn't want to come across as a Nazi, but his entire structure of thought and language was built during this time, and he can't find another one so quickly." Is there a better sociological-psychological analysis of this generation in one sentence?"

He also finds empathetic words for his mother's unhappy life, which did not meet her needs. And he describes - perhaps you have already experienced it yourself - the shock when he suddenly becomes aware of similarities with his own father, with whom he also has to share his own first name. Parents as an inescapable fate, the confrontation with them a lifelong task that the author does not yet seem to have mastered.

"Have you finally found us" - the eponymous sentence comes from a dream in which Edgar Selge searches for his parents as an adult - is an astonishing debut. I'd love more of it.