Nothing is certain: anytime, anywhere

Voland & Quist

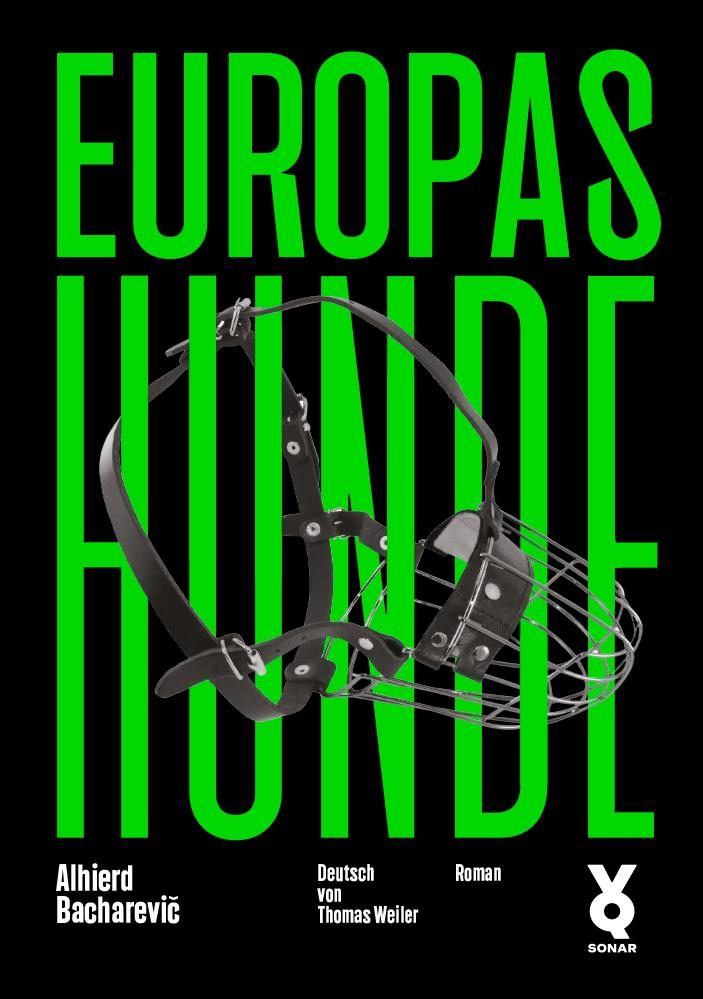

Voland & QuistAlhierd Bacharevič | Europas Hunder | Voland & Quist | 744 pages | 36 EUR

The author and essayist Alhierd Bacharevič published his novel Dogs of Europe in 2017 in his native Belarus, where it has since been banned. In spring 2024, it was published in German by Voland & Quist. The author writes from a magical perspective. What is that, a magical perspective? In Chad (I managed a project there in the mid-eighties, far from any city), an employee can come to work with a small cut on his finger and, when asked how it happened, might answer: "The saw bit me." Magical thinking gives everything a life of its own. This should not be confused with magical realism, the narrative strategy first adopted by Latin American writers but now widely used to soften the sometimes harsh edges of reality. For those who think magically, things are not "dead", as we describe them in rational thinking, but living and capable of action. This way of thinking, this method, underpins the entire novel. At the beginning of the book, a police officer suggests to Oleg Olegovich, the protagonist of Part I, that he probably knows many languages. Oleg answers in the affirmative, but then wonders whether it is he who knows the languages or in fact, vice versa. Normally, a book is read. Dogs of Europe is different. Yes, the reader reads the book, but the reverse is also true. The book also reads its reader.

This magical concept has an immediate effect on the language. There are completely unexpected images on almost every page, often with contradictory characteristics. It is so well written that this never seems far-fetched, artificial or rococo. No. Everything is coherent. And Thomas Weiler has done an equally fantastic job translating the work into German. Although Dogs of Europe is anything but an easy book, it is so engrossing that you won't want to put it down.

Right at the beginning, after the contents page, we find an excerpt from a poem by W. H. Auden about the death of W. B. Yeats. Two and a half stanzas from the third part of the poem are printed.

"In the nightmare of the dark / All the dogs of Europe bark, / And the living nations wait, / Each sequestered in its hate;"

The excerpt ends with the line: "Follow, poet, follow right / To the bottom of the night ..."

This conjured up the following image: Europe is on the brink of the Second World War, the dogs are the warmongers, the nations hate each other and the descent into the depths of hell is imminent. But Alhierd Bacharevič is manipulating us. He is not quoting correctly, because the three dots (...) do not exist in Auden's poem. Bacharevič has added them and at the same time omitted the following two lines:

"With your unconstraining voice / Still persuade us to rejoice;"

These two lines give the poem a different twist. In his novel, the author constantly wrongfoots us similarly. The dogs can be the warmongers, but at the same time we all are, caught by dog catchers when they deem it necessary. Everything has a double meaning.

Alhierd Bacharevič mentions - or alludes to - almost all the important novels of European culture from the last 200 years. Going back even further, the Odyssey and the Tales of a Thousand and One Nights are also points of reference. Likewise Pythagoras, who would rather be killed than disturbed while drawing circles. He appears twice, indirectly. The Wonderful Journey of Nils Holgersson with the Wild Geese by Selma Lagerlöf, a superb book, plays a major role, but Alhierd Bacharevič tells the story of young Nils in two different versions, neither as Selma Lagerlöf had conceived. The ghost of Kafta haunts throughout, but is only mentioned by name in the last part (The Trace), where a street in Prague is called Gregor Sander Street, an allusion to Kafka's story The Metamorphosis, the protagonist there being Gregor Samsa. And Dionysus, the Greek god of wine, who brings chaos and is the antagonist of the rational Apollo, who represents order, is also at play in this book. Why else are there so many people for whom drinking alcohol is the elixir of life? People are as entangled in their fate as are the characters in the early Greek tragedies. Didn't the protagonist of the final part, Teresius Skima, a handsome, fashion-conscious, mini-skirted man in the year 2050, get his first name from Teiresias, the blind seer from Greek mythology, who once lived for a few years as a woman?

The poetry excerpt at the beginning of the book is like a dedication, which struck me as a threshold to be crossed, head humbly bowed. We first enter the realm of Oleg Olegovich. He finds himself being interrogated by the police, who are trying to solve the death of a young man known to him. And it's about an made-up language, Balbuta, invented by Oleg. ("I called it Balbuta. God alone knew why. And that god was me."). Based on the French verb "balbutier", meaning to babble or stammer, Oleg's dreamt up language is one of freedom and great beauty, not particularly suited to strictness, discipline, law and judgment. Balbuta, this language of freedom, is the central theme of the novel. The pages are scattered with small sections written entirely in Balbuta.

In Part I (We are as light as paper), Oleg develops his language and eventually forms a small circle of four people who are able to speak it. But it's also about the dictatorship in Belarus and Russia's claim to conquest, the wish to reintegrate into its empire the territories lost after 1991. He portrays this in the games of adolescent boys and writes sentences such as: "Their hastily thrown-together peoples spoke Russian cheerfully, although on paper they had their national languages. Sounds kind of familiar, doesn't it?" A thinly veiled Vladimir Putin is portrayed in the novel as an immature child, trying to work out what some youths are up to. In the final part (The Trail), set in 2050, there is a "New Russian Empire", which once more includes Belarus. Opposing it is a Greater Europe which, strangely, has strictly monitored internal borders and its own national currencies. The euro and the Schengen area no longer exist. But the Russians have not yet been able to claw back the Baltic States from the West - they form the eastern border of Greater Europe.

The second part ( Of Geese, Men and Swans) is set in 2049 in a village on Russia's western border, not far from Minsk. The villagers live in great poverty, under constant surveillance and threat of punishment by caning. Almost all the young men are drafted into military service and never come back, especially from the southern border. Bishkek, Kabul, Tehran, Harbin and Pyongyang are all Russian cities, or at least that is what the villagers believe. But they also believe that Minsk, the old Belarusian capital very close to them, no longer exists. Paris, too, they believe to have been obliterated by a (perhaps atomic?) bomb. But Minsk and Paris do make an appearance after all.

All six parts of the novel are carried by people who think and question. Only these really matter. Oleg is one, as are two of the three young people with whom he shares his language of freedom. In Part II it is a boy, Part III (The Neanderthal Forest) an old shaman, in Part IV (Thirty Degrees in the Shade, Novel of a Summer Day) it is Oleg again, carrying a plastic bag through Minsk on a summer's day, a Minsk as it might have looked in 2015. He is supposed to deliver the plastic bag to someone for his mother. But can it really be Oleg? Like Oleg, the first-person narrator lives in a very small apartment, and as a reader you immediately think of him, but this narrator happens to see Oleg in a café, talking to his first student in Balbuta. It's a familiar scene from Part I. In Part V (The Time Capsule), Oleg appears as a teacher, although we only realise that it is him in Part VI (The Trace). In this last great story, 2050 is devoid of literature and poetry both in the East and West. The very idea is rather embarrassing. Books? Ugh!

In addition to the six main parts, in which there is always at least one element that acts as a baton in the relay race, there are also five shorter parts, poems and an Italian recipe - poetry of sorts purely in terms of flavour, and because it contains such sentences "... basil, cure me of jealousy, of Russianness and other delusions...".

Dogs of Europe is a rollercoaster. It takes some courage, but the rewards are rich. Fortunately, the publisher has set the page numbers almost floating at the top of the left-hand margin, a good two centimetres above the text. This allows you to hold on tightly as you read, like the handles in a car when it turns sharply or goes up and downhill. Why left and not right? Because the reader is a driver, not a passenger! Someone who acts and is not acted upon, by dictators for example. One who asks questions and knows that not all of them can be answered. This is how Alhierd Bacharevič dignifies his "clientele".

Those who pick up this book will be enchanted. However, in the final part, the boundaries between living in heaven or hell are becoming blurred. Will we ever know for sure? Is there a clear difference between the two? Aren't heaven and hell interchangeable, at least a little bit? Like the black and white dots of yin and yang?

But no life is without hope, even though the word hope does not appear once in 740 pages. The author puts the following words into Oleg Olegovich's mouth on page 21: "I know that the impossible is possible. Otherwise there would be no need to live." This is how we get through hard times.