Happiness is like a language that must be learnt

Transit

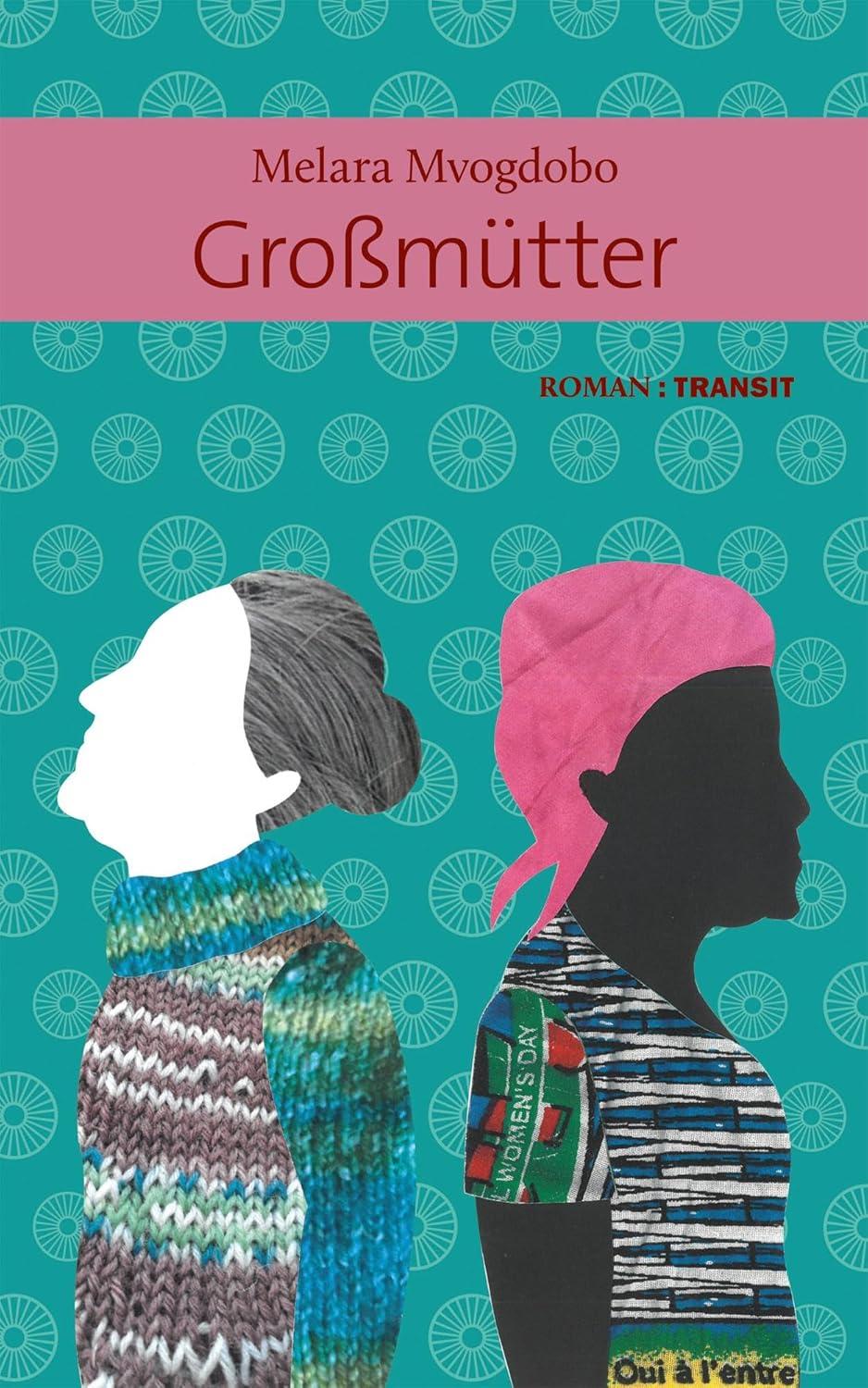

TransitMelara Mvogdobos | Goßmütter | Transit Verlag | 128 pages | 18 EUR

It's rare that a book appeals to everyone in our reading group. But this was the case with Melara Mvogdobo's slim, 128-page novel. When I read a ten minute except from "Grandmothers" on the subject of "Sharing" - we don't read a book together, but each read something on a predetermined topic - it provoked an unusually intense reaction, both in terms of language and content.

This may be because Mvogodobo, who was born in Switzerland in 1972 and has both Swiss and Cameroonian grandmothers, does not recount the story of her own assimilation or search for identity as a second generation immigrant, as Yandé Secks does in her debut novel Weiße Wolken (White Clouds), published a year ago. Instead she takes on the role of the granddaughter as listener, giving voice to two grandmothers whose roots could not be more different.

In small vignettes, also differentiated in colour in the book cover design, we learn about the coming-of-age of two women from two completely different cultural backgrounds. While in Cameroon it is the grandmother from a well-to-do family who resists the almost unavoidable expectations of a polygamous marriage, yet falls short in both her relationship with her husband and in her own personal fulfilment, the grandmother from Switzerland, who comes from a simple, rural background, does not have the problem of having to share her husband. Even so, she too is unable to live out her basic desires. Forced into a "marriage of convenience", she suffers at the hands of her husband's violence and dominance just like the Cameroonian grandmother.

The interweaving of these two life stories through brief everyday vignettes written in the first person is as disturbing as it is poetic, as the reader senses how close two cultures can be, despite their geographical distance, and how broad the similarities in male ignorance and stupidity, as well as female desires.

Melara Mvogdobo's unflinching depiction of polygamous relationships and everyday life in Cameroon recalls the Ghanaian author Amma Darko, and her vivid portrayals of both her experience as a migrant in Germany and the demoralising everyday life of women in Ghana, subject to the dictates of polygamous marriage as they are.

However, unlike Darko, who unfortunately has hardly written anything since her return to Ghana, Mvogdobo also writes in Grandmothers about the everyday life of a young farmer's wife in Switzerland, where dreams mean nothing and where, even in the old people's home, a blind eye is turned to a man's violence against his wife. In the resulting moral and physical liberation, which is depicted as minimalistically and unsparingly as the moral fragmentation and liberation in Ágota Kristóf's great trilogy Le grand cahier / La preuve / Le troisième, Mvogdobo leads the reader into a present in which the grandmothers, with the help of their granddaughters, learn to be happy as one might learn a language. And if, for example, happiness means eating pizza twice a week, then so be it!