Being able to love nothing and no one

Zsolnay

ZsolnayGianfranco Calligarich | Wie ein wilder Gott | Zsolnay | 208 pages | 24 EUR

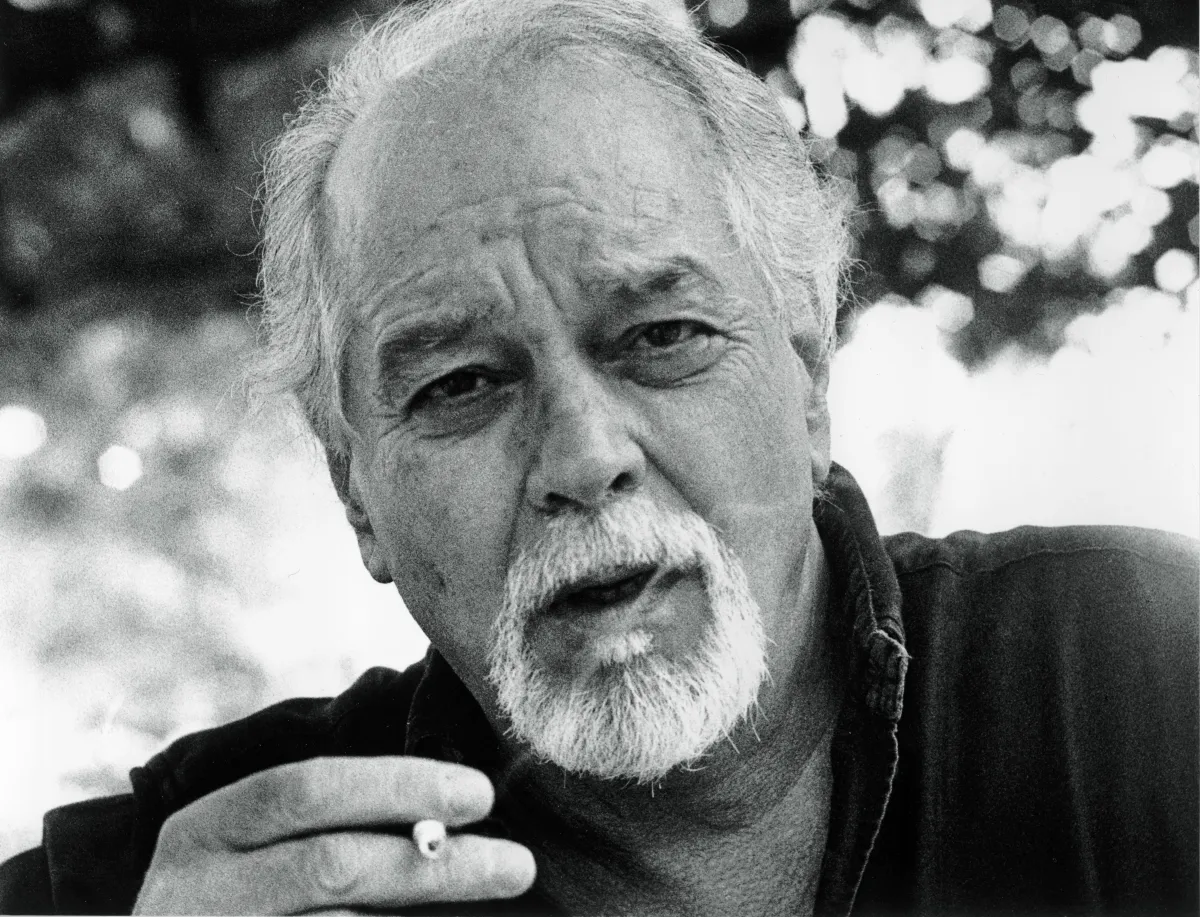

Whoever thinks of Gianfranco Calligarich, born in 1947, will probably know him for his astonishing literary rediscovery in 2022, when his 1973 debut novel The Last Summer in the City was republished and became a huge success. A novel set in Rome, it was anything but a romance - rather a melancholic paean to youth and dreams, reminiscent of the young Marcello Mastroianni in Fellini's La Dolce Vita and written so laconically and with such irony that now, 50 years later, it reads with the same freshness as it did then.

Calligarich's new novel is also written with this postmodern impetus. This time, however, it is not about his life, although there is a little Calligarich in this novel too, as Calligarich comes from a family in Trieste, but was born in Asmara in Eritrea in 1947 and then grew up in Milan. Calligarich had already explored his family's colonial involvement in La malinconia dei Crusich (2017) which won the Viareggio Prize; in Like a Wild God, he now turns his attention to Italy's earlier colonial involvement in present-day Ethiopia and Eritrea, where the foundations were laid for families like the Calligarichs to leave their homeland.

Calligarich tells the story of one of the many adventurers of the 19th century, of whom David Livingstone and Henry Morton Stanley were only the spearheads of a small armada whose exploits were kept alive as heroic stories told in every conceivable format until the end of colonial times. Today, these stories are being recontextualized, for example in Petina Gappah's captivating Out of Darkness, Shining Light, which no longer tells the story of David Livingstone, but that of his porters. Or, returning to the Ethiopian cultural sphere, an indigenous perspective is added, as in Maaza Mengiste's dark The Shadow King. In some, all fictional trappings are dropped and the story is journalistically dissected, accurately and mercilessly, as in Michela Wrong's great study I Didn't Do It for You: How the World Betrayed a Small African Nation.

Of course, Calligarich is also aware of this shift, and in his thoroughly researched story about Vittorio Bottego, the only fabricated voice is that of the narrator. The impossibility of telling this dense heroic epic of Bottego, who justifies his Wikipedia entry solely through a successful expedition down the Juba River and a failed and ultimately fatal expedition on the Omo River, is countered by Calligarch with several strategies.

In terms of content, he focuses on the fundamentally chaotic Italian politics of the late 19th century, which oscillated between colonial megalomania and a scathing criticism of the colonial program - officers of the Italian army like Bottego would repeatedly be driven to despair when long-awaited plans were thwarted and spontaneous alternatives had to be sought. Calligarich portrays his anti-hero in such a disjointed and postmodern way, that his actions seems consistently more like those of the greats of later pop culture - in line with the punk philosophy "It's better to burn out than to fade away", he restlessly explores previously undiscovered rivers, sometimes pointlessly. Not only does this have nothing of the heroic about it - there are the grotesque and cruel shootings of porters, for fear they might desert - but it is so often botched, even at the planning stage, that the reader is surprised that Bottego doesn't die on his first expedition. And the fact that Bottego sees "his" river as a "wild god", giving Calligarich's novel its title, doesn't make it any better, because ultimately the conqueror of such a river, mountain, desert or sea still sees himself as a new, even wilder, god.

In addition to these breaks in content, which rule out any heroic story from the outset, Calligarich also deprives his hero of a voice of his own. As with his young Roman hero in The Last Summer in the City, it is laconicism and irony that consistently break up the flow of reading and create the irritation that we ourselves naturally have with our own "colonial" expectations of a story that is also abundant in its cruelty. Calligarich does not allow this to happen. Instead, he hints, scatters bait, only to break off casually, for example when it comes to the many important half hours in the novel: "The half hours. But that's how it was. And always so far. That was as far as things went between the two of them in San Lazzaro. Delia Montenero. Nothing and no one would he be capable of loving except his life of discovery." This makes sense and is cleverly conceived, but readers who identify with the novel are likely to be disappointed because they are somehow always deprived of what they were promised.

As a novel, however, it works, not least because Calligarich is a chronicler of his time, reporting not only on the distortions of the human soul and politics of the past, but also on the neo-colonial desires of our present. After all, a failure like Bottego is astonishingly similar to the successful, neoliberal heroes of today's transnational corporations, who are hardly inferior to the colonial governments of the 18th and 19th centuries in their drive for expansion and the corresponding strategies.