Back to the Future

Penguin Random House

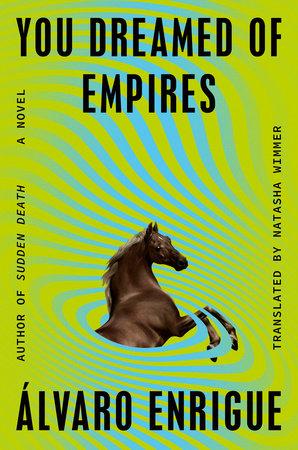

Penguin Random HouseÁlvaro Enrigue | You Dreamed Of Empires | Penguin Random House | 240 pages | 28 USD

Earlier this year, at a bookstore in Queens, New York, Álvaro Enrigue discussed his new novel, You Dreamed of Empires (first published in Spain in 2021; English translation, 2024) with me. He is a generous and erudite speaker, and held the audience’s attention as he described in detail the global effects of the so-called Columbian Exchange. He also described how Mexico City has changed since his childhood, and his excitement as a boy when the ruins of Tenochtitlan were discovered beneath the plazas of central Mexico City. If I recall correctly, he said that it was like discovering he had been living in Rome.

You Dreamed of Empires brings this buried past to light in a scant and engrossing two-hundred-and-seventeen pages. In spare, light prose, it reimagines the 1519 encounter between the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés and the emperor Moctezuma in the grand Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, surrounded by mountains, and floating in the midst of a lake. The narrative unfolds during the course of a single day. Cortés arrives in the morning and later that day comes face to face with Moctezuma. The wary, at times bumbling, and eventually world-altering meeting of the two civilizations is revealed through the preoccupations of various interested parties: the emperor, his sister, the mayor of the city, on one side; Cortés, his translators, and captains, on the other. The Guardian, in its review, accurately describes the novel as, in part, an “Aztec West Wing.”

Enrigue efficiently weaves in the background information, the layers of European and New World history, political intrigues and court hierarchies needed to follow the characters’ actions and strategizing. But understanding comes in bits and pieces. In an introduction of sorts that takes the form of a letter to his translator, he writes, “Don’t worry too much about the Nahuatl words you come across. Mexican readers won’t know right away what a macehual or a pipil is either. Let the meanings reveal themselves… You don’t need experience of parliamentary systems to understand how a European government works when you watch a political TV series made across the Atlantic, do you?… As you read, everything will be clear.”

The dislocation and sense of confusion caused by these unfamiliar words and multi-syllabic names with unfamiliar letter combinations, as well as the intricacies of a long-forgotten culture, puts the reader in the right frame of mind to appreciate the dislocation and sense of groping about in the dark that must have felt by all sides in the encounter. Like Moctezuma, Cortés, their allies, and enemies, the reader must make assumptions based on incomplete information, on a confrontation with foreignness—and continue moving ahead. In time, as Enrigue promises, everything does become clear. Or at least, as clear as anything can be when conversations between the two sides take place “through a double filter”: Malintzin, a Nahua princess and critical member of Cortés’s party, translates from Nahuatl to Maya, and Gerónimo de Aguilar, an Andalusian priest, translates from Maya to Castilian. And sometimes, the translators make their own decisions. “In Maya, [Malintzin] asked Aguilar… whether they should translate what Caldera and Cortés were saying for the benefit of the princess and the nobles and the priests crowded around the table. He whispered in her ear, also in Maya, that he didn’t think so, it was just conquistador chatter.”

The Tenochtitlan (or Tenoxtitlan) that Enrigue creates is a striking, startling place—“no dogs, no beggars, no food stalls; the ground was so clean you could lick it;” ruled by an emperor, who was “skilled, brave, and unpredictable; a formidable strategist,” and a fearsome warrior class, along with priests and their “impossible protocols,” their “shameless bloodbaths and cannibal luncheons.”

When, towards the end, Moctezuma climbs the citadel, and splashes his face with water, while the eagle warriors stream out from “colleges, palaces, and temples on their way to the Old Houses, ululating majestically as they went,” you can only marvel at Cortés’s belief that he could topple this empire — and the improbable way in which he did.

You Dreamed of Empires, along with the recent publication of fascinating studies like Caroline Dodds Pennock’s On Savage Shores: How Indigenous Americans Discovered Europe, (which Enrigue reviewed in the January 18, 2024 issue of The New York Review of Books), and David Graeber and David Wengrow’s The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity, mark the next stage in reevaluating this profound encounter and its consequences.