"People are only really dead when nobody thinks about them anymore" *

Astiberri

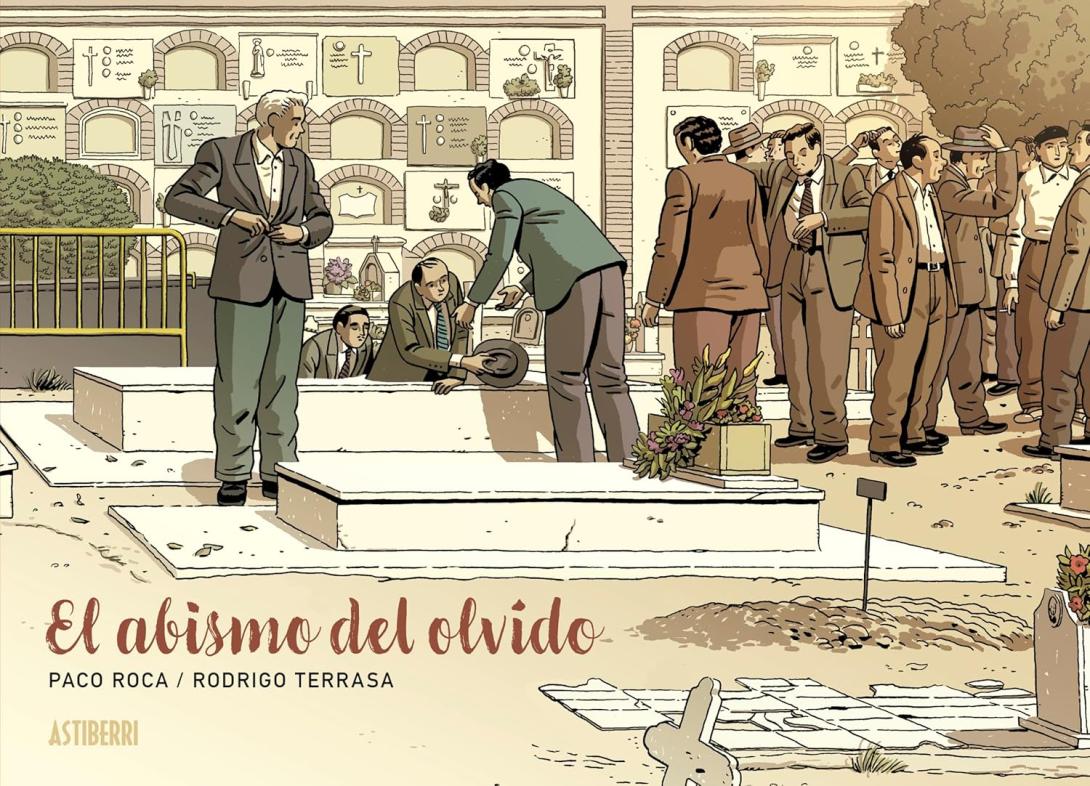

AstiberriPaco Roca, Rodrigo Terrasa | El abismo del olvido | Astiberri | 296 pages | 25 EUR

Leoncio Badía, a gravedigger in the 1940s during the Franco regime in Spain (1939-1975), is one of the protagonists of this graphic novel by Paco Roca and Rodrigo Terrasa. We watch him at his gruesome work of stowing dozens of delivered corpses in large mass graves. Unperturbed by his orders and his irritated colleague, he has taken it upon himself to preserve the memory of the victims, a dangerous and prohibited activity. To this end, he secretly places small, named vials into the graves to facilitate later identification of the bodies. It's an unusual perspective for readers to approach a topic that is omnipresent in Spanish society, that of the crimes committed during the long Franco dictatorship (the number of disappearances is estimated to be at least 100,000 to 150,000), which have left bloody and traumatic scars on many families to this day.

Shifting perspectives are a key feature of the authors' approach to this politically sensitive subject, beginning on the very first pages, where we observe a lizard scuttling into a hole in the ground, startled by the rhythmic pounding of footsteps. We soon realise that this is the sound of a firing squad taking up position in a compound in the east of the city of Valencia, where they will systematically kill people who, for various reasons, are deemed unacceptable to those in power - for example, because they are communists. The perspective then shifts to a young recruit, completely overwhelmed by events and not even understanding why he is there, before zooming in on one of the condemned men, whose fate is in turn linked to another protagonist.

Thus, the narrative style of this comic - drawn with the characteristic simplicity of the ligne claire - is both masterful yet always accessible, unfolding a complex structure that oscillates between various characters and levels, between the years 1940 and 2013. Transitions are often skilfully executed and fluidly designed, with explanatory flashbacks and digressions inserted into the plot. In some passages, however, these explanations do lead to a certain textual density, pre-supposing a historically interested reader.

Rodrigo Terrasa carried out extensive research for this book in order to be able to tell true stories of the people who died in the mass graves of Valencia - a process he explains in an epilogue, supplemented with photos. Paco Roca has also already explored his home city of Valencia in the biographical Return to Eden. This results in a sober, rather documentary view of events which, not withstanding the artistic flair that also incorporates surreal imagery of metaphorical and cosmological ideas, does characterise this graphic novel. To further substantiate the historical authenticity of the narrative, a photo of one of the deceased is integrated into the drawings at one point. This clearly demonstrates the work's didactic approach, which draws attention to grievances in Spanish history and contemporary society. For example, it delves into a controversial law from 2007, which allowed the families of victims of the dictatorship to exhume their loved ones. This is also one of the main narrative threads surrounding Pepica Celda, who in 2007, already eighty years old, sought to retrieve the remains of her father, executed and dumped in mass grave 126, in order to give him a dignified burial next to her mother. Her example shows how many bureaucratic hurdles have to be overcome in order to reach one's goal - often after many years. This law is a highly political issue and continues to polarize the debate about coming to terms with the years of civil war and dictatorship, a period in which many who would rather it was forgotten have absolutely no interest.

The authors repeatedly emphasise and demonstrate that the human need to bury one's loved ones with dignity runs deep. In doing so, they also reference - with vibrant colours in a contrasting style - the Greek myth of Achilles and his friend Patroclus, whose ghost pleads for an honourable burial after Patroclus is killed in battle. The gravedigger Leoncio Badía and the octogenarian Pepica Celda each wage their own exemplary and unflinching war against an inhumanity that refuses to acknowledge the need for a dignified burial and thus an appropriate culture of remembrance. Readers must decide for themselves whether they share the conviction that - as the graphic novel claims - forgetting is death, commemoration brings people back and opening graves liberates their souls.

In any case, El abismo del olvido offers a shocking and, due to its many perspectives, multifaceted insight into a complex -and in Germany, little known - part of Spanish history and its repercussions to this day. It is particularly vivid and emotional in the moments where concrete suffering is recounted, be it a child's final encounter with his father before his execution, or the clandestine observation of a shooting by a young woman concealed in a tree.

+++

Did you enjoy this text? If so, please support our work by making a one-off donation via PayPal, or by taking out a monthly or annual subscription.

Want to make sure you never miss an article from Literatur.Review again? Sign up for our newsletter here.

*Bertolt Brecht