Come in. I'll show you my pictures. I painted them myself.

Reprodukt Verlag

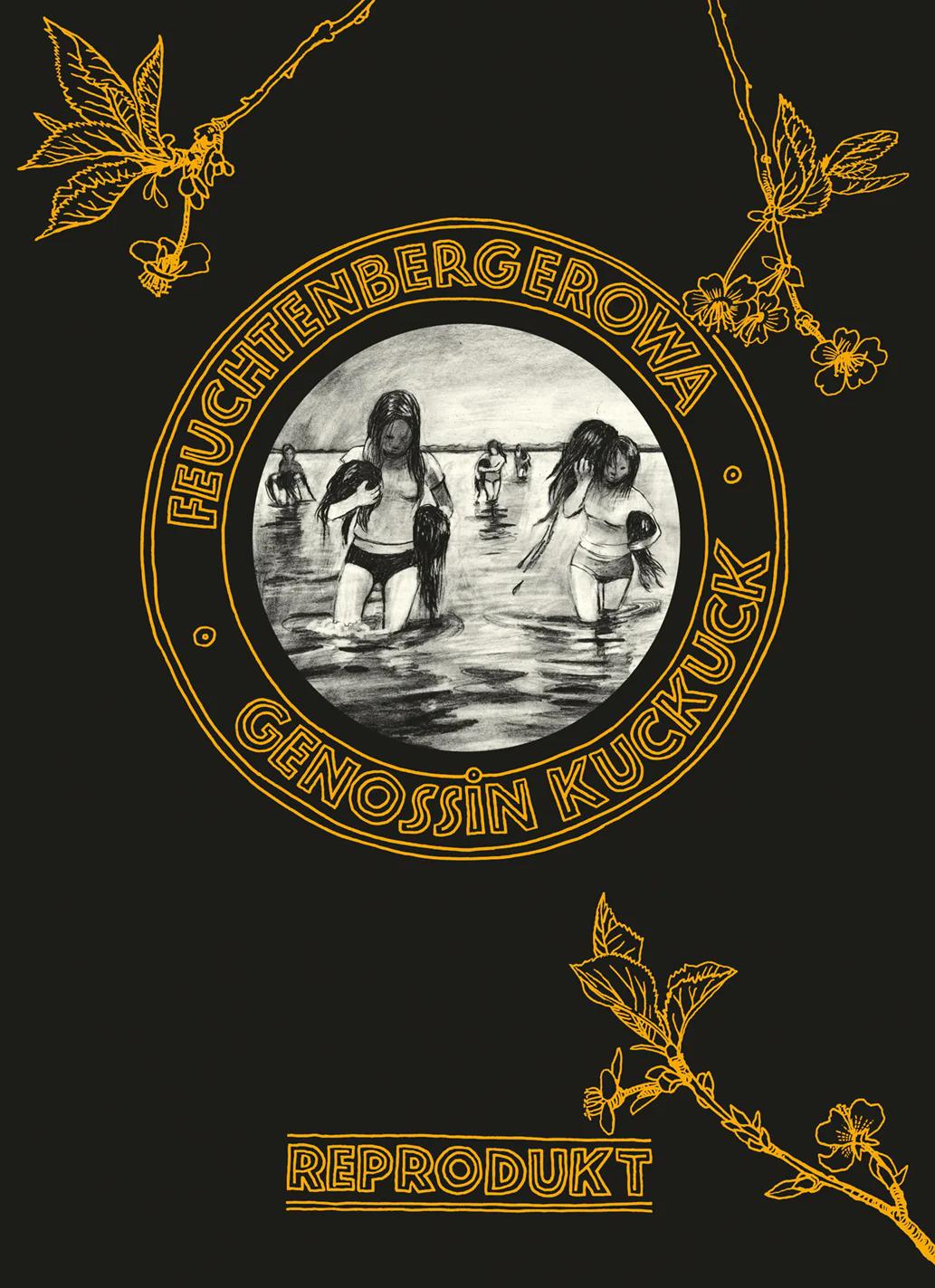

Reprodukt VerlagAnke Feuchtenberger | Genossin Kuckuck | Reprodukt Verlag | 448 pages | 44 EUR

So now, some award-worthy literature! Anke Feuchtenberger's Genossin Kuckuck (Comrade Cuckoo) may not have won the Leipzig Book Prize, but it did make the shortlist: it's been a long road for the medium to become a recognized art form. The work illustrates, through labyrinthine narrative paths, the story of two girls from the 1960s to the early 1990s in the German Democratic Republic (GDR). It is only logical that it has now also been nominated for the Max und Moritz Prize at the Comic Salon in Erlangen, important within specialist circles.

As children, we used to meet in our garden in fine weather to read comics. Mickey Mouse, of course, was top of the bill. This easy reading was tolerated rather than welcomed by our parents, who always asked why we couldn't read something more appropriate, why it always had to be these rubbishy magazines. We couldn't particularly argue our case, other than that we just really enjoyed them. The awareness that this was a unique form of storytelling came later. When Hugo Pratt's 'Corto Maltese' appeared in the Zack magazines, it triggered first a hunch and then a search for clues that quickly led to Eisner and Spiegelman. It was immediately obvious that this was art. And now that in Germany too, prestigious book prizes for comics are within reach, there is no longer any talk of rubbish.

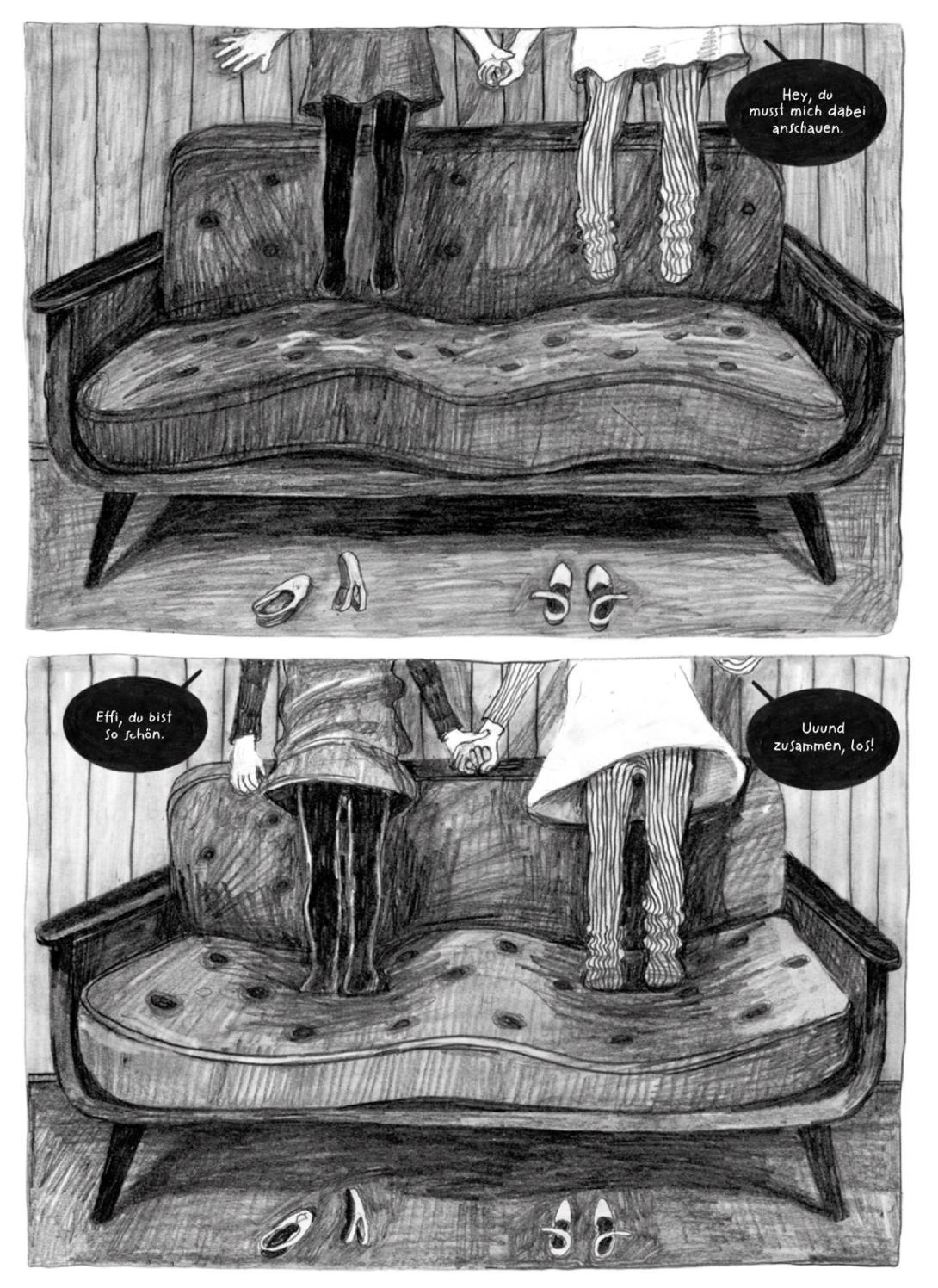

And yet Anke Feuchtenberg's Genossin Kuckuck is, quite frankly, not a comic at all. Picture book would be a more fitting description, if that term wasn't so embedded in children's literature. So, illustrated novel, i.e. graphic novel, is actually apt for this work. Even if otherwise, it makes little sense to distinguish between a comic and a graphic novel, this difference is stylistically relevant in Feuchtenberger's work. Her narrative style repeatedly avoids some of the principal elements of serial storytelling typical of comics. Looking at the first few pages, for example, the bouncing of the protagonists Kerstin and her friend Effi on the couch (see pictures on the left) is not shown in a horizontal panel sequence, which would emphasise the chronological sequence of events. Instead, the vertical division of the individual images and their distribution over several pages puts the temporal aspect back behind the spatial aspect, creating a kind of delay, a certain floating weightlessness, parallel to what is being depicted.

However, this also sets a narrative baseline for the entire book, as this weightlessness, this gravity-defying storytelling, is the central narrative device in Feuchtenberger's graphic novel. She very often dispenses with a chronological plot development, taking more an associative, erratic and fragile approach, which in turn corresponds to the fragility of the characters and their social circumstances. In the same way, references to myths, fables, local legends and fairy tales continually set the story free from reality. On the one hand, of course, this is due to the childlike view of the world that the protagonist Kerstin initially holds. However, it is also a deliberately chosen stylistic device of detachment, reminiscent of the cinematic storytelling of Guillermo del Toro, who, for example in Pan's Labyrinth, uses the filter of the fairytale to obscure the view of the 'real world' on the one hand, whilst simultaneously interpreting and illuminating it. We can see that Anke Feuchtenberger perhaps also had in mind Bertolt Brecht's V-effect; in keeping with his spirit, she prefaces each chapter with a heading that represents a reflectively distanced antithesis to the classic development of suspense. This allows her to talk about, among other things, abuse, physical and psychological violence, social pressure and political persecution in the GDR, without having to lay these things down in concrete terms. All of this tends to appear behind or between the images, but is not hidden by this narrative style, sometimes even becoming more clearly visible if you engage with this sophisticated narrative approach. And best of all, there's the added sparkle of the memory of a fairy-tale childhood.

Anke Feuchtenberger's graphic novel is a visually stunning, enigmatic and disconcerting book, that takes a very intimate and subjective look at its protagonists and their surroundings. Whether this is a novel, a comic or something completely different is ultimately irrelevant. What is important is to read it with an open mind, to let go of too-rigid ideas of plot development and image sequences. The book deliberately breaks away from narrative rules and boundaries, rising above them. It is therefore important to pay close attention to Rosi's words at the end of the story: Come in. I'll show you my pictures. I painted them myself.