Between Eros and Thanatos

© Reprodukt

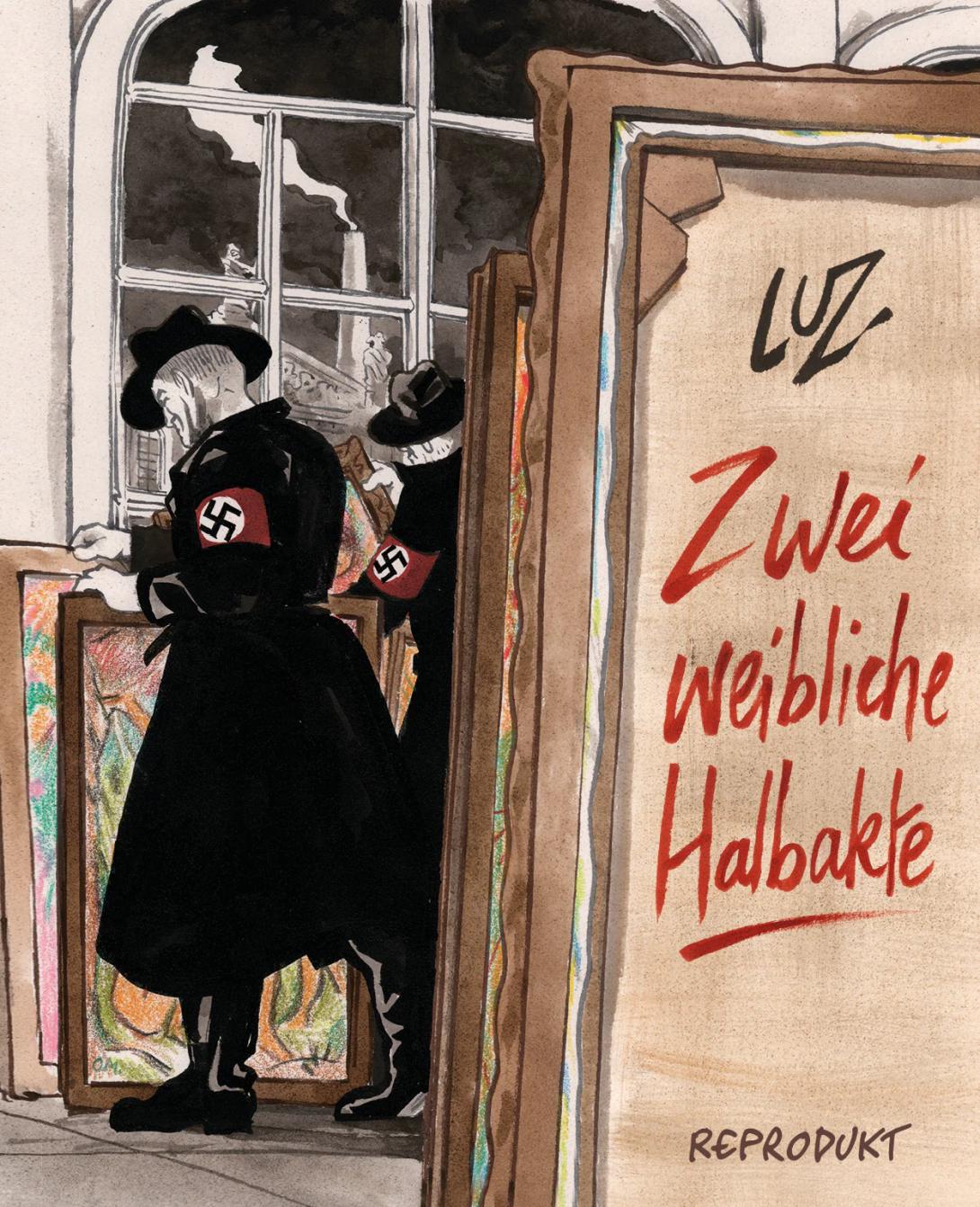

© ReproduktLuz | Two female semi-nudes | Reprodukt Verlag | 192 pages | 29 EUR

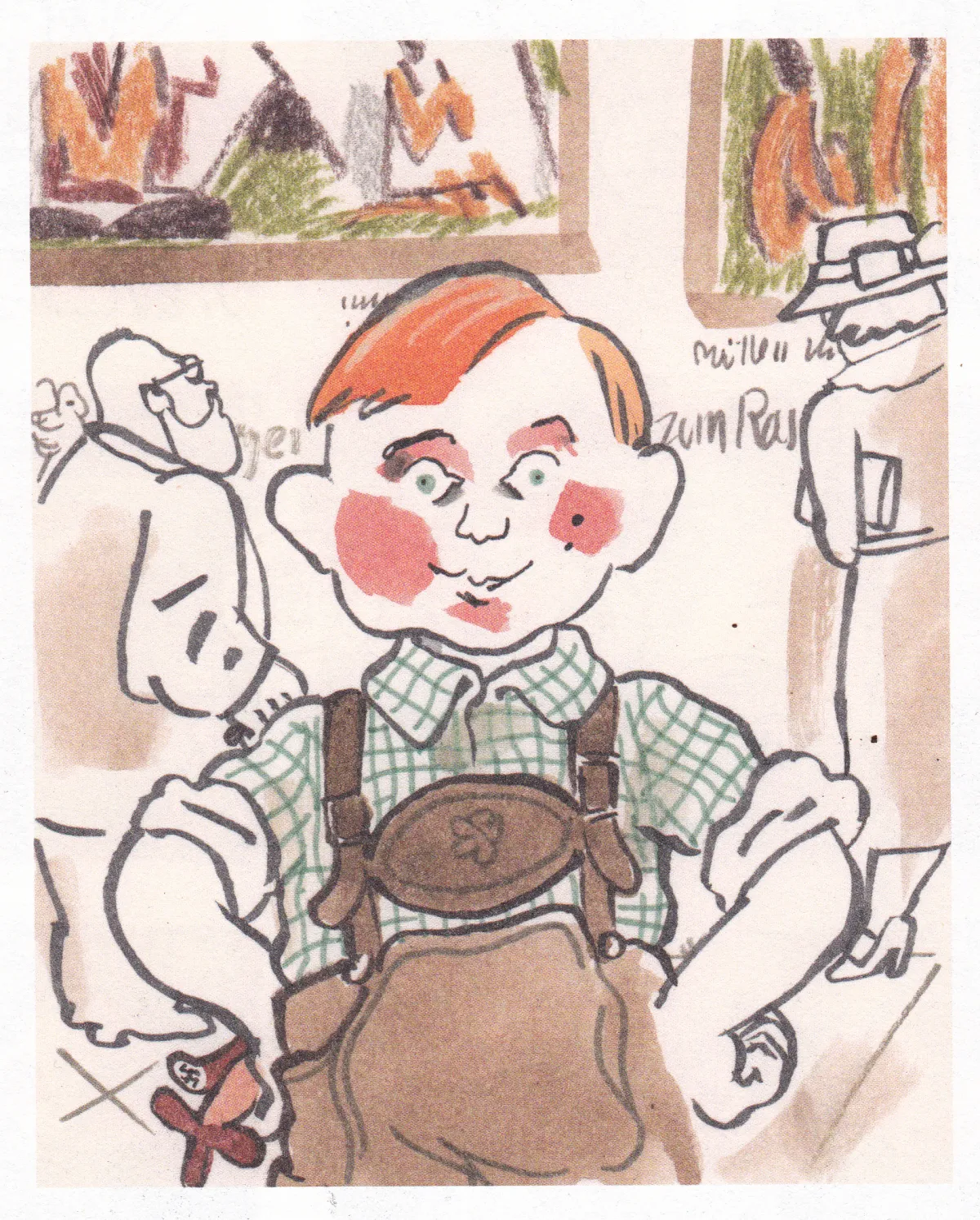

The little boy stops and looks at us. He is actually looking at a picture in an exhibition, but the illustrator's perspective makes us feel as though we're the ones being observed, and we stare back - we are the picture. At first the boy is sceptical, he seems uneasy, disturbed by what he sees, but then he fixes his gaze on the artwork. The toy, a small fighter plane in his hand, becomes completely irrelevant and insignificant. He squints his right eye and immerses himself in the sight, sinking and falling completely out of time and space. He no longer just looks, he sees.

This is the moment: Lothar, the boy, has fallen in love with the picture. Eros has shot his arrow and hit him in the heart. But the very next moment he is pulled away - one last look, then the crowd comes between him and the picture.

The painting in question is "Two Female Half Nudes" by Otto Mueller from 1919. Lothar saw it in 1937 at the Munich exhibition "Entartete Kunst". There it was hung far too low, to emphasise its inferiority, being a "cultural Bolshevik depiction of pornographic character". Merely children's scribblings, worthless rubbish, this low placing is meant to convey - but it brings the picture right to Lothar's eye level.

Luz's graphic novel "Two Female Half Nudes" now tells us the moving and gripping story of Otto Mueller's painting of the same name. Luz uses a surprising narrative trick to do so. We experience the story exclusively from the limited perspective of the painting. The reader always sees what the painting 'sees'. At first glance, the framing of the panels remains faithful to the classic comic book layout, with uniformly sized frames lined up consecutively. Then you notice that these are interrupted by oblique or tilted shapes. The panel sizes vary repeatedly, sometimes occupying an entire page, then shrinking to the original size. What does not change, however, is the format: Luz's comic develops a radical form of storytelling here by adapting the entire panel structure to the physical dimensions of Mueller's original painting (120 × 90 cm). Each page reproduces this vertical format, making the individual panels resemble sections of a museum exhibition display - the story itself is exhibited, unfolding before the painting and before us. Göbbels, Göring and Hitler pass by, museum visitors focus on the work, other works of art stand opposite it and seem to correspond with it. If the picture is turned, tilted, hung or slanted in the course of its history, the panel systematically follows suit. This strict formal discipline turns the book itself into a kind of inverted, walk-in history gallery: the reader does not move through a classic comic book sequence, but lets the events emerge, whilst at the same time being virtually forced by the perspective to identify with the picture, to merge with it. What drove Luz to seek out and build such a close connection to the work?

Luz, whose full name is Rénald Luzier, was one of the formative minds behind Charlie Hebdo. As co-founder of the magazine's relaunch in 1992, he was instrumental in developing a satirically provocative and socially critical style. His cartoons were known for their sharp irony, their ability to get to the heart of complex issues and their willingness to break taboos - until January 7, 2015 changed everything.

Luz was not a victim of the attack on the editors of Charlie Hebdo because he was late to the editorial office that day. By the time he arrived, the attackers were already on the run. Which can be seen as an incredibly lucky coincidence: The assassination struck Luz to his core, personally and artistically, triggering an existential crisis: fear and guilt overwhelmed him, leaving him unable to draw for months. In May 2015, he announced that he was leaving the editorial team of Charlie Hebdo. The period following the attack was marked by an intense search for healing, a confrontation with trauma and the struggle to find a way back to drawing.

With "Catharsis", Luz not only succeeded in returning to art; the volume is also a reflection on this process. In it, Luz deals with the attack with brutal honesty and intimate confrontation, addressing his barriers, fears, doubts and self-reproaches: "I now felt the need to show what it looks like in my inner world." "Catharsis" shows him lying in bed with his wife on his birthday, the day of the attack, and his subsequent late arrival at the office, when the perpetrators had already fled. The Freudian interplay of Eros and Thanatos opens up for Luz and the reader with almost unbearable clarity: while Luz and his wife make love, his friends and colleagues are being murdered. "Catharsis" thus becomes a kind of visual diary documenting his internal struggles. However, it also marks the beginning of a healing process, both personal and artistic.

In this context, Luz's new graphic novel "Zwei weibliche Halbakte" can be understood as a further step on this path of reconstruction. It is a work that revolves around the fragility of people, their relationships and their work, but also addresses situations of vulnerability and the search for healing. The turbulent history of Otto Mueller's painting serves as its backdrop.

The comic begins with the scene of the painting's creation in a forest near Berlin. With the painter's first strokes, we see the image emerging. Mueller's first dabs and areas of colour on the canvas open up views of the picturesque surroundings and of the model Maria, Mueller' wife. And from then on, we look with the artwork through its more than one hundred years of existence up to its current home in Cologne's Museum Ludwig.

We see with the painting how its owner, the lawyer Littmann, takes his own life in 1934 because of the reprisals of the National Socialists. We see how the painting is sold unsuccessfully at auction in Lucerne in 1939. We see how the art dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt is seduced by the beauty of the painting and exchanges it for other works of art before later selling it himself. We see how the painting was donated to the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum (now Museum Ludwig) in Cologne in 1946. It remained there until 1999, when it was returned to Ruth Haller, Littmann's daughter, from whom the Museum Ludwig reacquired it in 2000. We see all this through the eyes of the painting.

Luz works with his characteristic drawing style throughout this comic - a concise mixture of quick, seemingly sketchy strokes and precise emphasis on the essentials. As in his adaptation of the novel "The Life of Vernon Subutex" by Virginie Despentes, his special ability to capture complex atmospheres and characters with only a few accurate lines is evident. The figures are not naturalistic, but rather typically caricature-like, though always capturing the essence of the person and the situation.

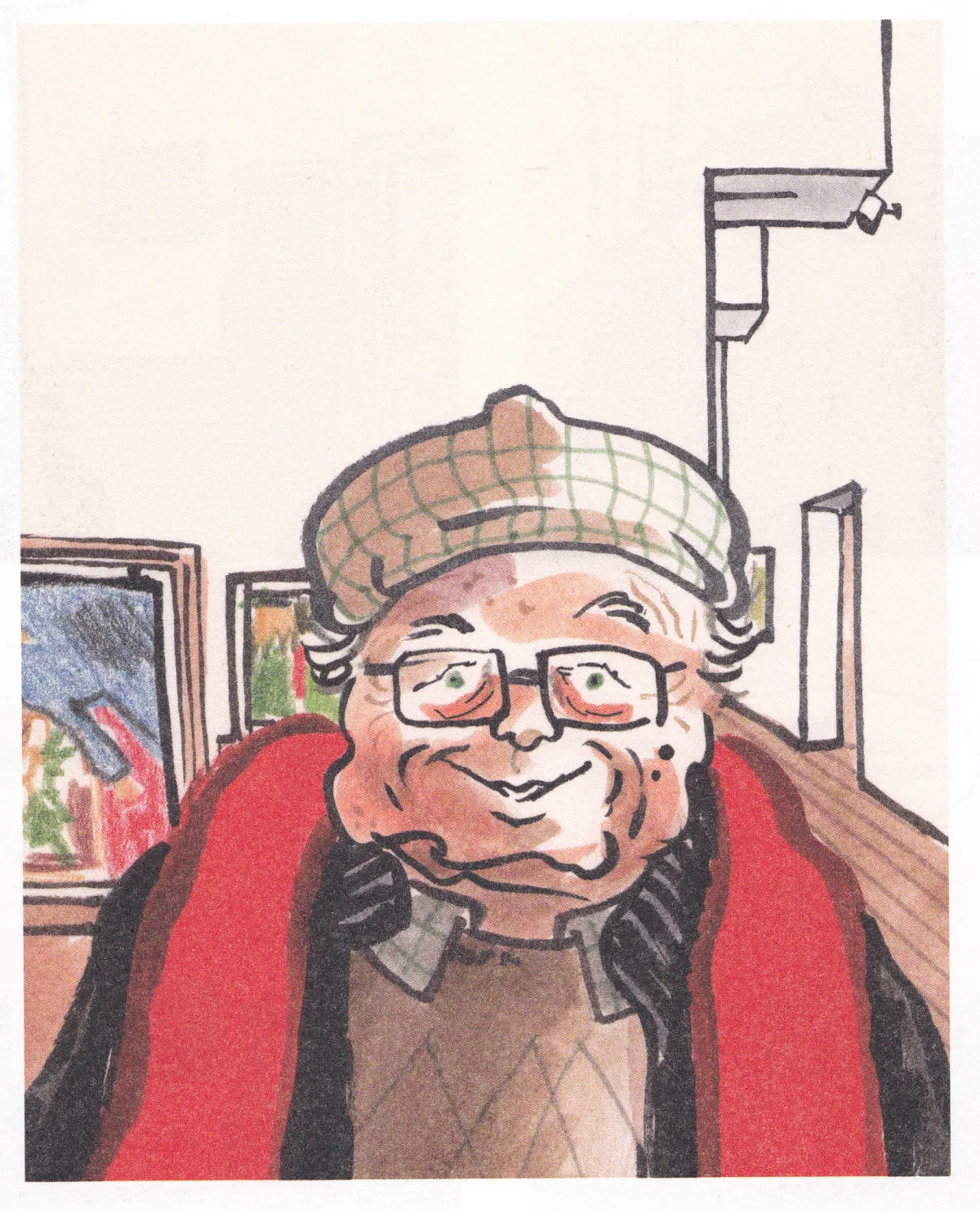

And so, of course, we recognize him immediately. Lothar has become an old man, he drags himself somewhat wearily through the tour of the Museum Ludwig. But Lothar it undoubtably is! And then they meet. His somewhat vacant gaze suddenly becomes focused! At first the old man is sceptical, he seems uneasy, disturbed by what he sees, but then he stares intently at the work of art. The cane, which he now needs for walking, becomes completely irrelevant and insignificant. He squints his left eye - no, he smiles; it used to be his right eye - and immerses himself in the sight, sinking and falling completely out of time and space. He no longer just looks, he sees. And the moment is repeated: Lothar, the old man, has met his love again. Eros has shot another arrow and hit him in the heart.

But Lothar is called away again. Probably for the last time... One last look - the museum is closing, it's getting dark: Eros and Thanatos.