Plugging the leak

It's summer in the global north (which is winter in the global south), and for the month of August Literatur.Review is bringing them all together, publishing previously untranslated or unpublished stories from the north and south of our world.

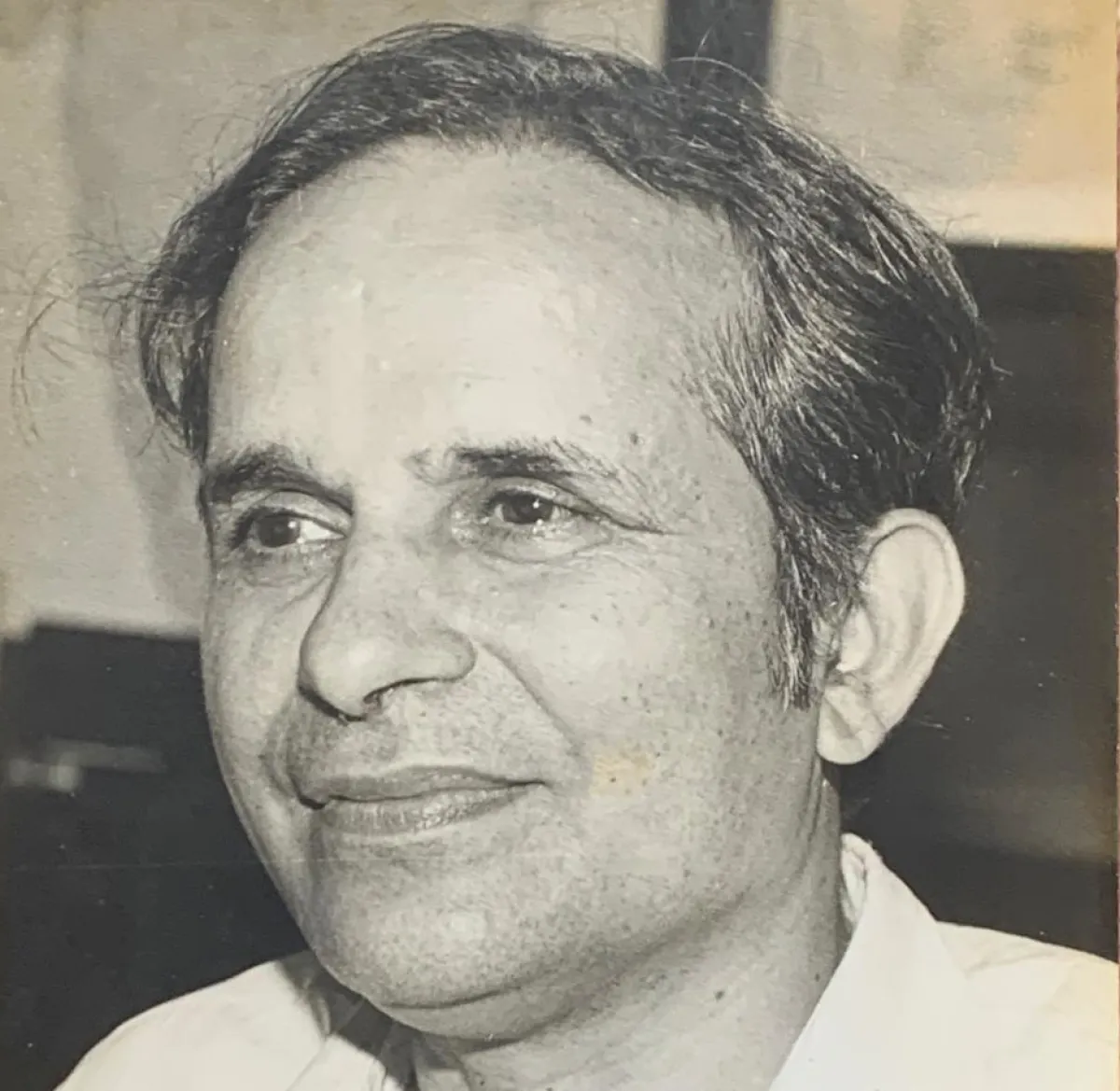

Ghanshyam Desai (1934–2010) was a modernist, experimental short story writer. He was born and brought up in the small principality of Devgadh-Baria, now in Gujarat.

Thats my father coming home, I’m sure. Isn’t that squat figure by the warehouse, him? Yes, it is him – bare chested and with his black cap. He had walked off that morning ordering us to mind the shop. With this attitude, what sort of business could you expect? Most likely he had gone to Ismail’s place to have a smoke. Ba grumbled, ‘Is this Ismail the only friend he’s managed to find? Why, the man’s just out of jail! It’s either ganja or cards all day long!’

That’s how it was, day in and day out. Ba and Bapuji don’t get along at all. I have no idea when it started, but ever since I can remember, they’ve always been at each other’s throats. Mostly he’d thrash her as if pounding grain. My mother would cry, protest and swear. This would invite a further beating. I would side with my mother. Not openly, but in my heart. I am very young and not very strong, while my father is built like a rakshas. One blow and he can knock down a wall. I was terrified of him. I usually sat silently in a corner, but as I grew older, my turn too came.

Bapu has a grocery shop. The shop in front, our living quarters at the back. In our village, homes were built without any kind of plan, and generally consisted of seven or eight rooms laid out in a straight line, one leading to another. If you looked in from the outside, you could see half-open sacks of grain, flies humming over iron containers of jaggery, cane baskets filled with dates, a scale lopsided with heavy weights; the swing in the first room; the bed in the middle room; the shadowy form of my mother in the kitchen; the bean creeper climbing the wooden frame in the backyard, and next to it a shed built of bamboo where you could wash and bathe. Like a sparrow making frequent fluttering visits to its nest, my father would come here to take a leak.

Ba would say: ‘Your father has two bad habits: guzzling cupfuls of hot tea dhag-dhag every fifteen minutes, and pissing it all out dhag-dhag in another fifteen.’

This was an unfortunate habit of my mother’s. Once she got going, she could never stop. And that too in front of my father! Even when beaten, her howls would be interrupted with curses.

Where has Bapa disappeared again? I saw him a moment ago passing Nannu Paanwala’s shop, swaying side to side like an elephant, holding the hem of his dhoti, and spraying jets of paan. He must be wandering nearby. If we are lucky, he may have gone to Raman’s stall for a cup of tea. When he comes back he’ll find some excuse to start a fight.

‘His home is like a war zone,’ people said. ‘There are constant battles going on there. How would Goddess Lakshmi ever enter such a home?’ The root of my parents’ conflict revolves around wealth. Ba came from a wealthy family. She was married when still in her cradle. When she began married life, her husband too was wealthy. The decline started soon after. All five homes they owned were sold. I have heard that they also owned the biggest jewellery shop in the village, and were forced to sell it. Bapa then tried his hand at various ventures but failed to succeed at any of them. Advised by an astrologer to deal in red-coloured items, he started a business selling dried red chillies. The only result was to induce severe burning in the chests of family members. Another astrologer prophesied that dealing in liquid items would fill his coffers with gold bricks, so he began to sell adulterated ghee and oil. Nothing changed. The family’s capital gradually disappeared. Finally, when there was barely enough money for food, he opened a grocery shop. If you could not sell the grain, you could at least eat it . . .

So, far from marriage fulfilling a rich girl’s expectations, my mother was obliged to sell her ornaments. She protested vehemently, but there was no option. ‘If he would only give up his friendship with Ismail and his addiction to tea, our household would be back on its feet,’ she lamented daily.

Bapa would bellow, ‘Get off my back, woman! It’s you who brought ill-luck the moment you stepped into the house! What can I do about it? I’ve been running about like a rabid dog, but nothing succeeds.’

Ba was disgusted by my father’s habits. She had burnt the midnight oil to read all four parts of Chandrakant and endured her mother-in-law’s taunts to finish reading Yoginikumari. She loved to read. She knew the Ramayan and the Mahabharat by heart, and if she could not lay her hands on anything else, she would read the newspaper wrapping on packages.

This incensed Bapa. ‘So you think yourself a great scholar, do you? Reading, reading all the time! Isn’t that all you’ve ever wanted to do?’ he would snarl and slam her in the back.

‘Yes, and I would have continued to do it if I did not have to produce your children!’ Ba would reply bitterly. Her love of reading, her interests, her simple nature – everything had evaporated after her marriage.

And is it any surprise that she had become so bitter? What a lot she had endured! She had suffered four miscarriages. The first foetus was a two-headed, three-eyed monster. Ba barely survived that time. The government doctor had given up hope, but she survived somehow. Later, she often wished she had not.

Her eldest surviving son was reserved and obedient. He sat unmoving wherever he was placed. Through his narrow slanted eyes he would watch silently the arguments, fights and beatings. At most he would turn his head away. Ba would say, ‘See how happy my Mota looks when I take him on my lap and feed him a lump of jaggery! He strokes my face just as though he understands my pain!’

When Mota was small, he too was often thrashed. But as he grew older he refused to tolerate it any more. When he was thirteen or fourteen, he ran away from home. We searched high and low, reported the matter to the police and sought our own relatives’ help. But in vain.

Ba would reminisce: ‘My boy had such delicate skin. If only he had stayed back a few more years, he would have been strong enough to return his father’s blows. He was already so tall and well-built. He would have been such a support to me!’ She thought about her eldest son continuously. On every festive occasion, or whenever anything special had been cooked, she would sigh, ‘If only he were around . . .’ And her eyes would mist over with tears.

I often feel Mota’s presence next to me. He talks to me. His narrow eyes focus intently on me. He strokes my face. I say to him, ‘Why did you have to run away?

Together we could have protected Ba. We would have straightened Bapa out.’ He is often on the point of tears. Then he shakes his head and raises his hand to pacify me. I reply, ‘Don’t you worry so much, Mota. I am here, aren’t I? Just let me get a little older and start earning, and see how well I take care of you. I won’t let him harm a hair of your head.’

Ba often hugs me tight and says, ‘Son, you are my only support.’ And to tell the truth, it is only because of this that I endure Bapa’s cruelty. Otherwise I too would have followed Mota long ago.

When Ba can’t stand it any longer she says, ‘Get me out of this hell. I cannot bear it anymore.’

But this hell is like a bog. The more you try to get out of it the more it sucks you in. And I lack the strength to pull myself out. My helplessness makes me mad. I can’t stand and watch silently like Mota did. I feel like picking up a five-seer weight and bashing Bapa’s head in. But I lack the courage. And I’m just too small.

Look, my father seems to be coming home. From his gait it seems that he is in a foul mood. If someone happens to cross his path, he’s had it.

Bapa was climbing the steps to the shop. ‘Get off your ass,’ he yelled and grabbing my hand flung me out of the way.

‘Oh, ho, just look at the conqueror of the world, Sikandar the Great himself!’ Ba greeted him.

Eyes red with anger, Bapa seized her by the neck and punched her twice or thrice in the back. Something snapped within me. Consumed by rage I lost all control over myself. I knocked down a sack of grain and began jumping on it. ‘Why are you hitting her?’ I screamed. ‘Let go of my mother, let go!’

Seeing me stomp on the sack, my father let go of Ba. He stood up panting, and glared at me. Taking hold of my ear, he twisted it hard. As I tried to wrench his hand away, we both tumbled onto the sack. He thrust my hand aside and hit me on the head. Everything went dark and before I knew it, a violent kick landed on my waist and I doubled over with pain. I wanted to scream, I wanted the whole world to hear me howl, but the sound would not leave my throat. Eventually, the pain subsided. When I looked up I could see my father walking slowly from one dark room to the next. He passes by the swing, and scratching his head, enters the kitchen. ‘Some tea,’ he orders as he plonks down unsteadily on his heels. Pouring the hot tea into the saucer, he slurps it down noisily. I don’t know why but I can’t bear the sound. I am overcome by an uprush of disgust for my father, for his unrestrained violence, for his shop, for the way he sits on his haunches slurping endless cups of tea, for the bamboo shed where he goes endlessly to piss.

My head was throbbing, my back and sides were sore, and I didn’t think I would ever be able to escape this hell. Bapa stood up, and hitching up his dhoti, made his way to the bamboo shed.

Suddenly I found that Mota was standing by my side. ‘Did you see how Bapa bashed us? Did you? He drank his tea, dhag-dhag and has now gone to pee, dhag-dhag, ’ I said.

Mota’s tiny eyes lit up with laughter. How he laughed. Here I stood, welts rising all over me, my body burning with pain, and all Mota could do was laugh? As if to clear my confusion he said, ‘Hey, little chap, why don’t we just solder his leaking pipe?’ Both of us doubled up with laughter. ‘Oh won’t that be fun! How he will hop, hop, hop!’

We couldn’t stop laughing. And as we laughed, a single tear slid down my cheek on to my tongue. The taste of salt lingered in my mouth.

Glossary

Raksha: Demon

Ba, Bapa: Gujarati for mother and father

Dhag-dhag: Quick quick or fast fast. It implies force and burning heat

Jaggery: A traditional non-centrifugal cane sugar

About the book

The short story published here appeared in 1977 in Ghanshyam Desai's collection of short stories Tolu, which will be published in English translation for the first time as part of the Ratna Translation Series 2024. We would like to thank the publisher and the translators for the rights to this preprint.

About the translators

Aban Mukherji is a freelance writer and translator. She has a master’s degree in History.

Tulsi Vatsal, a graduate of Oxford University, is an independent researcher, writer and editor. Both have co-translated a number of books from Gujarati into English Their translation of Dukhi Dadiba and the Irony of Fate has been shortlisted for the Valley of Words translation awards.