It's all nonsense here!

Lektora

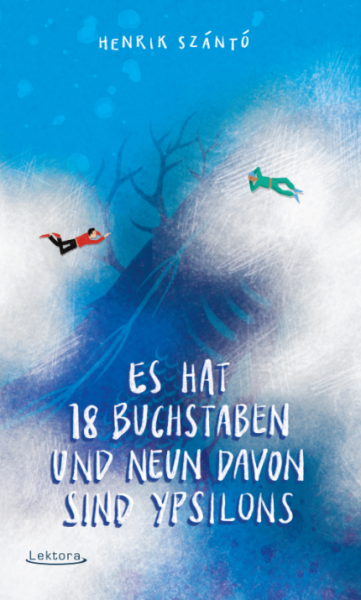

LektoraHenrik Szántó | It has 18 letters and nine of them are ypsilons | Lektora Verlag | 104 Seiten | 14,80 EUR

On entering the ORF studio in Klagenfurt for the Days of German-Language Literature 2024, you are briefly confused. The jury are arranged in a semicircle on the stage, with the chairman sitting in the middle. But surely the writers and literature itself should be the focal point here? So where is the reading area for the authors? A quick look round reveals the lectern, located between the audience, facing the jury - to all intents and purposes part of the audience, suggesting that the author and studio audience should listen to what the jury has to say to them. The layout of the room immediately reveals how this event is structured and the power relations it follows. Whether this setting is a successful idea in this context is doubtful. At the very least, the set-up clearly demonstrates that places, spaces and spatial details can greatly influence one’s perception of events within them. Rooms reflect realities, focus on certain details and can sometimes even change reality. A space is therefore never just that, but always an expression of something residing deep inside it.

This is exactly what Henrik Szántó is talking about in his text 'A Staircase of Paper', which he will be reading at the 48th Days of German-Language Literature. A house is about to be demolished after the discovery of an aerial bomb. And now it speaks - no, screams - in a breathless echo of the memories etched into its walls. The house has always been a silent observer of all that goes on; it has seen everything, but been powerless to intervene. Yet the spirits of its dead inhabitants still haunt the corridors of its memory. In temporal synchronisation, generations of postmen mill around the entrance hall, delivering eviction notices, love letters or bills. Current and former residents hurry past eachother, unseen, in the stairwell. Student parties are celebrated, love stories ignite and fade. And slowly but surely, a particular memory surfaces. Before 1933, the house was owned and lived in by the Sternheims, a family of Jewish watchmakers. However, one of the SA men who smashed the Sternheims' shop window during the pogrom night of 1938 also lived here, and later, the Gestapo officer who had arrested the family and then taken up residence in one of the confiscated apartments. Only in his case does the house come alive, angrily whispering the echo of this memory to him without cease, with the hissing of his radiator. Layers of memory overlap and entwine. What will remain of them when the house is demolished and replaced by a new building? An impressive funeral chorus of fragmented and repressed memories is intoned: Grandpa was involuntarily in the SS.

Henrik Szántó presents a furious tableau of images with this text, impressively recited. As a spoken word artist, he is able to create a rhythmic and dynamically paced collage of memories. This expanse of language and memory causes us to question how and what we remember, repress or forget. The echo of the text resonates for a long time and settles in our consciousness: Where are the forgotten in the walls to find peace when the spaces for memory disappear,are torn down? Memory needs something tangible!

The jury found much to praise: Klaus Kastberger said: "This text shifts things into one another in a breathtaking way." Philipp Tingler was "touched by the openness of the text", Thomas Strässle found the interweaving of time “very virtuosic."

Despite the jury’s plaudits, the author surprisingly came away empty-handed, as if the text had been lost somewhere in the corridors of ORF Carinthia. Was it perhaps mislaid in the labyrinthine power structures of the jury? Or could the jurors no longer remember their own review - had they suppressed it? This text in particular deserved a stronger echo. To help preserve its memory and give it the space it deserves, we would like to refer you once again to the homepage of the 48th Tage der deutschsprachigen Literatur 2024, where you can either read it yourself or listen to the author read it aloud.

Henrik Szántó is an author whose name must not be forgotten.