The wall

It is summer in the global North and winter in the global South. Reason enough to bring summer and winter together in August's Literatur.Review and publish previously untranslated or unpublished stories from the North and South of our world.

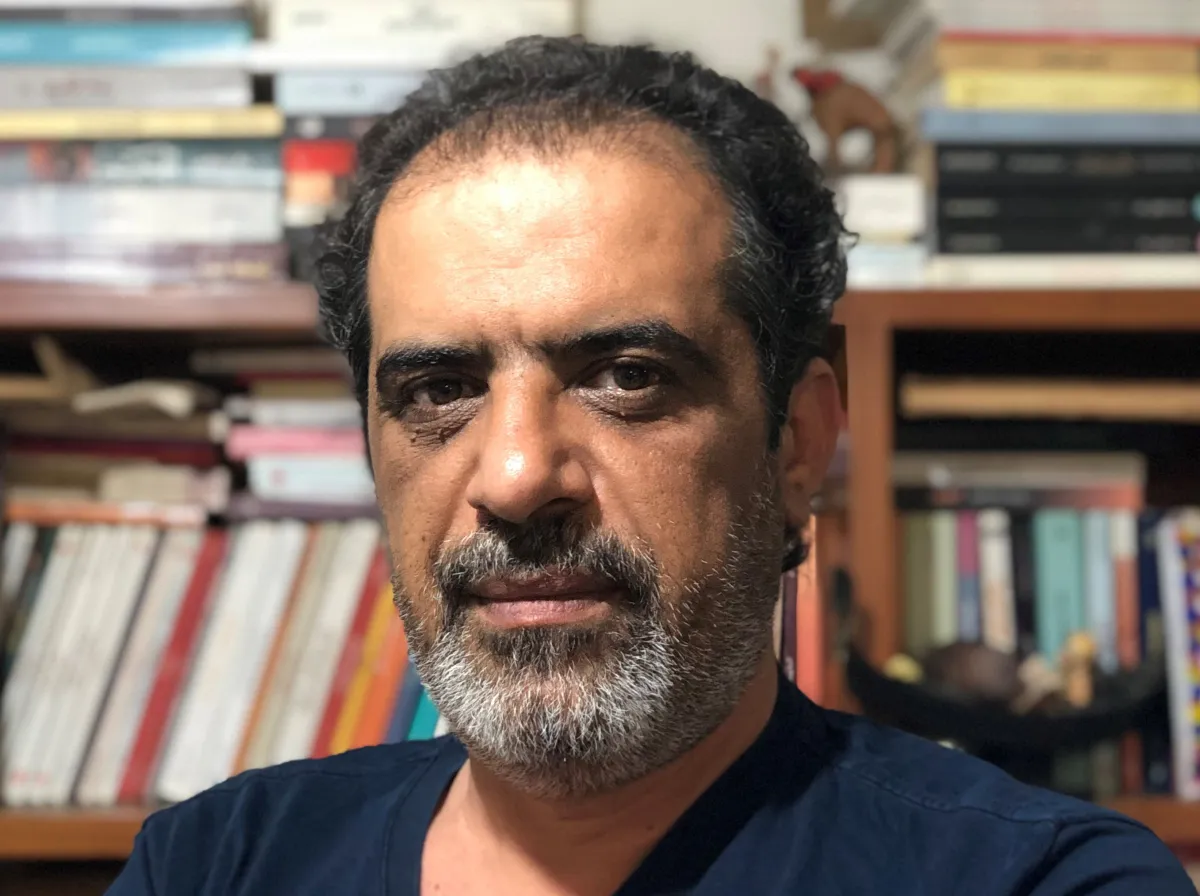

Rami Tawil is a novelist, short story writer, translator and screenwriter. Born in Syria in 1974, he has written several screenplays for television and cinema, including two broadcast series: Al-Hurub and Sira' al-Mal.He has worked for the cultural page and literary supplement of the Lebanese newspaper Al-Akhbar. In literature, he has published several novels with Dar al-Saqi: Raqsat al-Zill al-Akhira, Hayawat Naqisa, Qubba'at Beethoven; as well as collections of short stories: Qabla an Tabrud al-Qahwa and Imra'a 'Ind al-Nafidha. In children's literature, his works include: Lasta Wahidan (shortlisted for the Sheikh Zayed Prize - children's literature category, 2023), Ajnihat Adam, and Mamlakat al-Musiqa. He has also translated several novels from Italian, including Ma'jam 'A'ili, Shakl al-Ma', Hubb, and Al-Mustahil.

As children, we used to spend most of our days in the street, escaping our narrow and cluttered family homes. Actually, it wasn't a street at all, but rather a narrow alley wedged between two rows of low, haphazardly built buildings. Yet, by tacit agreement, we called it "the street". It was our space, the scene of all our childhood activities: running, playing football, marbles, and our favourite game of all, Cops and Robbers.

We never felt cramped there. The two hundred and five paces separating one end of the alley from the other seemed like an immense expanse, a veritable adventure playground. Only the stone wall at the southern end of the alley sparked our unease and curiosity. On the north side, we could sneak off into nearby neighbourhoods similar to ours, but on the south, we came up against this wall, an impassable barrier stopping us in our tracks and obscuring whatever lay behind it.

Our childish imaginations conjured up all manner of stories about what might be behind this wall. Some of us saw verdant gardens stretching as far as the eye could see, surrounding a sumptuous palace inhabited by a prince and his dazzlingly beautiful princess. They owned many horses and rare animals, including lions and tigers. Others, on the contrary, imagined an abandoned house inhabited by djinns and spirits, who fed on children they captured at night. Some went so far as to tell tales of children's heads found decapitated and thrown behind the wall, or of traces of blood and young girls' hair, cut and then braided, hanging from the top of the wall like ropes, serving as a warning to keep us away. We would only need to hear a story once before we would start recounting it as though it was a personal memory. And yet, none of this stopped us from trying to break through the wall, to make little holes in it, the result of long hours of effort, in order to spy on the unknown and feed our childish dreams with ever more wild and terrifying images.

For years, this wall was the boundary we dare not cross. When we ran, it was our finish line. When we played football, it served as our goal. Every day, we walked these two hundred and five steps dozens of times, between the northern entrance to the neighbourhood and the wall to the south. Until one morning, we were woken by the din of machines and the tumult of workmen: the wall was being demolished.

We gathered in the middle of the alley, wide-eyed, terrified of what might emerge from behind the wall. The work went on for a long time, throwing up thick dust that obscured our view and fired our imaginations tenfold. Staring into that unknown side, we swapped whispered guesses, each of us fearing that our worst predictions would come true while secretly hoping that reality would disappoint.

Finally, the dust cleared. The wall had become a pile of crumbled stones. All that remained was a barren wasteland, with no trace of trees, no princely palace, no haunted house. Just a wasteland strewn with rubbish. And we couldn't understand why such a place had been hidden from us for so long.

Immediately, all the legends we'd invented vanished from our minds. We were overjoyed: at last, we'd be able to venture beyond the confines of our alley. The days passed slowly, as the rubble was cleared away. We continued to play in the usual space between the alley's northern entrance and its southern end, where the wall had stood. The ground was levelled, the earth dug up, then buildings erected. An asphalt road was laid between them, apparently extending our alley. Yet none of us ever ventured down it. As if the old legends still lurked there.

It was in this neighbourhood that we grew up, watching generation after generation of children play in the alley. They, too, were content to walk the two hundred and five steps before turning back, ignoring the part now clear and open to them - but this didn't stop them from passing on to each other the legends we'd invented as children about what lurked there. Stories we told them, thinking we were making fun of childish imaginations.

This story is taken from the collection A Woman at the Window, published in 2023 by Dar Al Saqi in Beirut.

(English adaptation based on the French translation from Arabic by Rita Barrota.)