...if childhood is a tomb

Editorial Pulpo

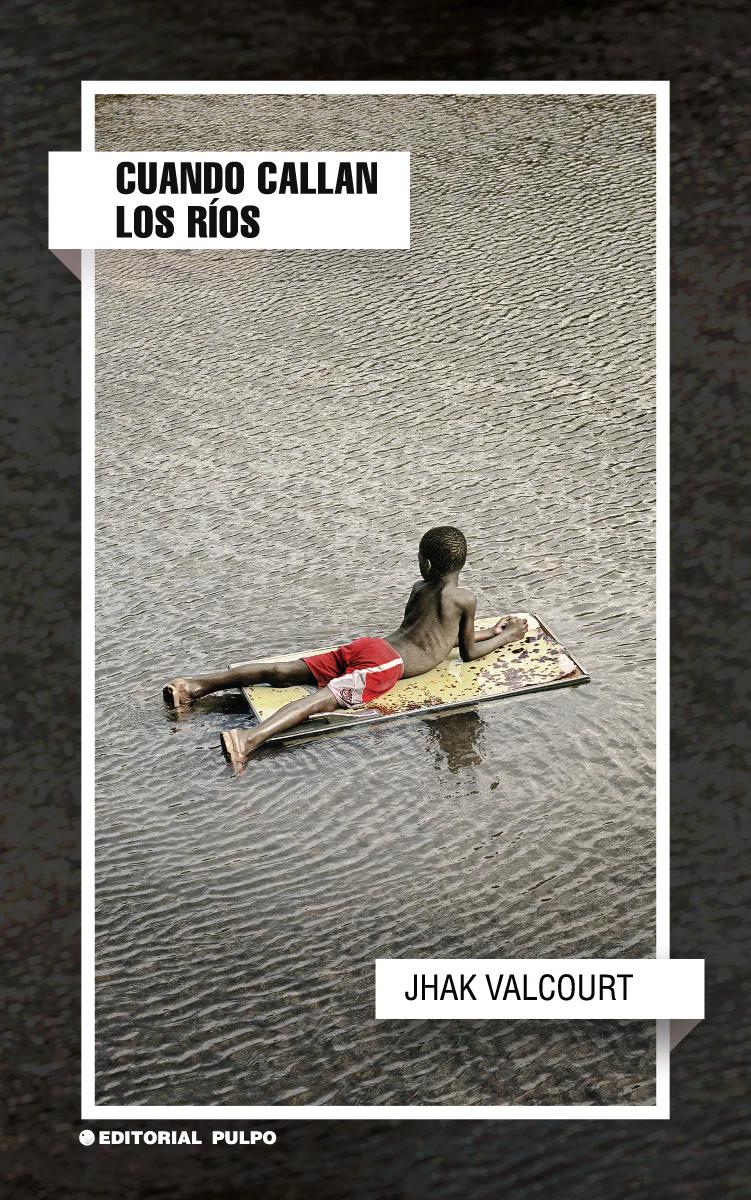

Editorial PulpoJhak Valcourt | Cuando callan los ríos | Editorial Pulpo | 53 pages | 18 USD

You know the sweet spell of memory;

a river pushes you away from the banks,

drives you toward the ancestral landscape.

Listen to those voices: they sing of loving pain

and melancholy. Listen to that tam-tam; it gasps

like the breast of a black girl.

In recent years, Haiti has suffered numerous grim and traumatic events that have eroded its institutional foundations to the very core. Since the assassination of its president Jovenel Moïse in 2021, the country’s socio-political crisis has only worsened beyond measure. One can only guess at the numbers of kidnappings, rapes and deaths of civilians at the hands of armed gangs, as well as through the negligence or complicity of the political and business sector of the island. This maelstrom of violence and uncertainty has caused many thousands of Haitian nationals to seek asylum in neighbouring countries in an attempt to repair their shattered lives.

In response, various Haitian figures, both local and from the diaspora, have turned to art to depict this complex reality, with varying degrees of success. One of these artists is Jhak Valcourt, who from his home in the Dominican Republic not only evokes and denounces the ravages that eat away at the foundations of the first black nation of America, but also carefully examines the moral and spiritual condition of the immigrant.

In this sense, the present book When the rivers are silent, composed of only 21 poems, serves as a road map of the poetic self that evokes a childhood in search of the stolen and lost home. For this, Valcourt draws on an imagination rich in Haitian landscapes and cultural elements. This pilgrimage should evoke warmth and rest, and thus resemble the mythical "Guinea road" once envisioned by Haitian poet Jacques Roumain, where the wind glides with its "long tresses of eternal night" and the streams "shiver like rosaries of bones". But Valcourt, looking back into the storage room of childhood, discovers that it is nothing more than a funereal limbo:

...if childhood is a tomb

where only black roses grow,

then here,

in the loam of misery

are we alone in the great Night?

The poet quickly strips childhood of its sanctuary, giving centre stage to fire, misery and death. Every vestige of innocence and languor is worn away by a penitential sickle, and the elegiac mood of the collection becomes more visceral and desolate. Valcourt breaks away from the tradition of French romanticism in the vein of Victor Hugo or Arthur Rimbaud and their approach to childhood lost in a framework of social inequalities. More important is the identity crisis of the poetic self that, shaped by immigration, has been fragmented and stripped, as the South Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han would say, of "narrative anchors":

But after so much leaving

After so much abandonment in every corner

In every nook and cranny of the journey

How is it possible that there is still something of you left?

This leftover,

always ready to leave again

because you don't even belong to yourself.

In short, Valcourt addresses an existentialist questioning of the immigrant and his place in a society that tends towards marginalisation. A depersonalised immigrant, a torn flag on his chest, who does not quite fit into the world. The poet turns to the faded and traumatic vignettes of his childhood to seek answers, searching for the warmth of his roots. But, above all, Valcourt focuses on pain, on the traumas of being a "man out of time" in a strange and hostile land; the permanent failure of a homeland that crumbles (the metaphor is Jacques Viau Renaud's) "like an isolated breeze of grass in the wastelands."

It should be pointed out that Jhak Valcourt ascribes to a thematic line that is trending, especially in Spain: that of shining a light on the oppressed and invisible immigrant. The young Nicaraguan William González Guevara, for example, in works such as Los nadies (2022) or Inmigrantes de segunda (2023), approaches the subject from the perspective of a poetic self sensitive to the exploitation of a mother who, being an impecunious foreigner, has to work herself to the bone simply to make ends meet. On the other hand, in Invocation to the Silent Majorities (2022), Spanish poet Paloma Chen addresses the cultural clashes, rejection and insults her Chinese parents received and kept to themselves, questioning concepts such as submission and dignity.

Jhak Valcourt in Literatur.Review: What we keep quiet in the „truck“

But Valcourt does not limit himself to reproducing laconic or circumstantial images of this reality. There are keys to his style that show his attempts to capture its subterranean narrative - his reluctance to use capital letters, the fragmented verses, the claustrophobic environment that hovers over the poetic self and its traces of anguish. The author also collects stories along the way that together seek to rescue testimonies buried by haste, fear and dishonour. Beyond the dark forge of borders, Valcourt tries to vindicate his protagonists with more lyrical and noble solutions:

They left Luis at the border

where he will become a tree

to give shade to future migrants.

Ultimately, When the rivers are silent is aimed at exploring the psyche of that helpless and forgotten immigrant. An immigrant who carries, in addition to crosses and weary dreams, a story. It would seem that, beneath the murmur of those rivers of happy or tragic memories, of that lost child, lies a man that the author invites us to become acquainted with. A man who is pained by the fate of Haiti. After all, Jhak Valcourt, with this book of poems, ventures with a firm fist into a genre that some have already described as documentary or new social poetry; which seeks, among other things, to serve as a spokesperson for those who remain shrouded by the crests of hunger and desolation, war and oblivion.