Pregnancy cravings

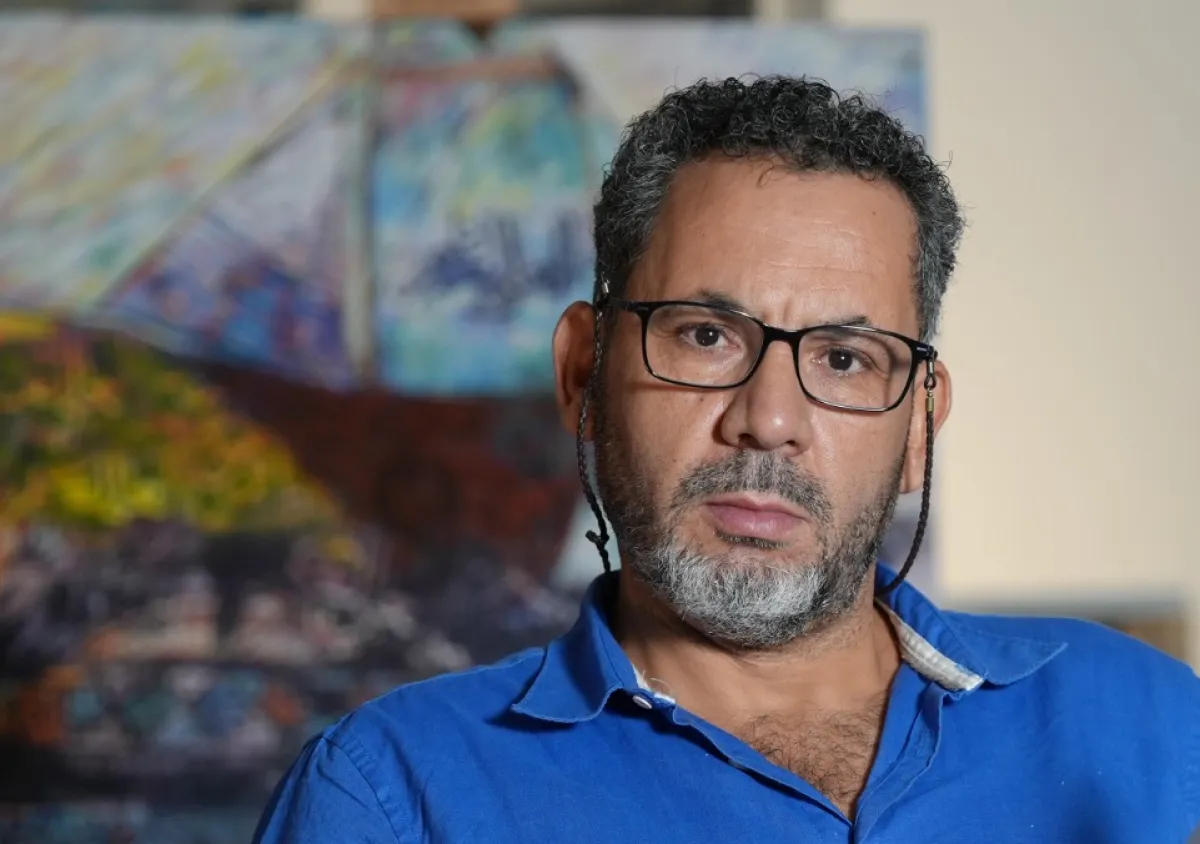

Hassan Marzougui is a Tunisian writer and media professional, holder of a DEA in civilizational studies from the University of Tunisia and producer of cultural and documentary formats.

The fact is, he wanted to kill me.

He pointed his gun at me, just like that, quite naturally, and said in a rough voice quite at odds with the gentleness of his face:

- If you don't take back what you've published, I'll put a bullet between your eyes.

Then he returned the pistol to its elegant black holster, spat in my face, and walked away.

The image of that black pistol adorned with the government emblem remained etched in my mind for several moments. It stuck there, terrifying me at first, but as I thought back to the feigned gruffness of his voice, and his gentle face, I felt a cold sweat run down my back.

I wondered, as I wiped away his saliva: can a policeman, whose livlihood I pay for with my taxes, really kill me with a gun provided by those same taxes? What would he say in court? Would he claim to have killed me because of a simple piece of fiction he didn't like?

That, in itself, is a story. A smirk escaped my parched lips, and I felt my shirt absorb the moisture sliding down my back.

I wasn't brave enough, even though I was convinced that this kindly face, camouflaged behind a forced, rough voice, was more lost than I was. He wanted me to believe, with this harsh posturing and his gun in his hand, that he had the courage to kill a writer branded a traitor.

Suddenly, a scattered thought gathered in a shadowy corner of my mind, in the manner of old papers and strewn debris accumulating on the sidewalk of an abandoned street:

A policeman wants to quell a scandal ignited by a text written by his writer cousin, by extinguishing it with a bullet fired from a "national" pistol. And this writer cousin, in turn, wants to incorporate this bullet into a text that would make him a 'real' author. One whom people would read after discovering his bullet-riddled corpse. Critics would consider this text - after my death, of course - a rare example of writing from personal experience, in the spirit of those great authors who did this. That bullet would make me a great writer.

The same wry smile returned to my pale lips. I stood up. My cousin had disappeared.

And since I'm a citizen who fears the police, either talking to them or even about them, and since things had come to the point where a gun had been held to my face, I withdrew the text on the spot. But it was too late: many people, whether I knew them or not, had already read it, alerted by the stir it had caused. It had circulated on numerous websites, both "yellow" and "white".

I still have to confess that I'm a cowardly citizen, but I wanted to be a brave writer. So I invented narrators for my stories, like dogs who left no subject untouched. I didn't really believe in fiction. I needed something real, a fact, an event. I needed visible prey to deliver to one of my dog-narrators to chew on like a chicken leg.

I withdrew the text after it went viral and people read it, and I lost out twice: once when that spit hit me in the face and tarnished my dignity, and a second time when my text was broadcast as a sin, not a story.

It was only after receiving a summons - which took the form of a 'courtroom' in the house of my Uncle Siddiq, the head of the family - that I was able to dispel the fear that had gripped me since the day of the gun, although the dampness running down my back reassured me a little.

At this meeting, all the voices I heard were naturally rough, no affectations. Uncle Siddiq had gathered us in his reception room. He's the oldest member of the family and I sign my texts with his name. He knew my grandparents, my cousins' father, my father, and all the family's deceased, but he's often muddled when it comes to the newborns. We call on him in crises to feel connected as a family, around a patriarch. When it comes to other conflicts, he hardly features. He only intervenes in disasters of the past, to give his opinion on matters dating back to a time we have little knowledge of. He is both narrator and witness. Everyone considers him to be the only one who still holds the truth of the past, truths required to resolve the conflicts of the present.

And now we needed him for this strange conflict, foreign to the family.

Uncle Siddiq began with a sermon of religion, custom, kinship and law - law he didn't know, but he quoted the word out of courtesy to my policeman cousin. This was all to convince me that I had dishonoured my cousins, and to convince them, themselves, that they had the wisdom and greatness of soul to forgive me, and that the honour of their father and paternal grandmother could not be shaken by a wandering scoundrel like me.

These words appeased some, but not all - especially not the one with the gentle face. He's the policeman the family is proud of, the one who stands by them in critical moments, and behind him stands a whole state - or so they like to think.

I let them smash the words over my head like bricks, and felt the dust of their insults settle over my face. I had to bite my tongue. The arguments I kept to myself would have been no match for the verbal bricks and spit raining down on me (my cousins had inherited this annoying habit of spitting as they spoke from their father, just like my grandfather).

My uncle attempted to interrupt the flow of insults:

-After what your cousins have said, you must realise the extent of the offense you have inflicted on them, and on all of us. You therefore have no choice but to apologise and declare before everyone that what you have written is nothing but a lie, pure slander.

The one with the gentle face spoke:

- With your permission, Uncle Siddiq.

Then, addressing me:

- We will accept nothing but a written apology, published on those same sites where your damned text appeared.

Uncle Siddiq asked what the word "sites" meant, but no one answered. They had no time to explain a concept this old man would understand with difficulty, if at all.

My gaze met that of the policeman, who stroked his gun. I then remembered his disgusting stream of spit.

- Very well. I apologise to you, cousins, in front of our eldest, haj Siddiq... Everything I wrote was pure fiction.

Signs of relief appeared on the uncle's face, but a firm voice broke the calm:

-No. Don't play games with us, impostor. Call a spade a spade. Everything you've written is a lie. And until you explicitly mention the word "lie" in your written and published apology, we won't accept it.

- I hope that's clear, Uncle Siddiq, and you're my witness. So that you don't come later and reproach us for our actions.

- It's clear, my son.

The older brother's tone was firm and definitive.

What was striking about this meeting was that one moment they were judging me as a teacher and the next, an intellectual. They threw reproaches in my face saying that I was a disgrace to intellectuals and the literati. That a true intellectual writes with honesty, does not lie to the public, and must serve as an example to his students... And they concluded with this sentence: " You? An educator of generations? You're a disgrace to education."

No sooner had their destructive machine fallen silent than they scrutinised me like a cousin who had betrayed the family honour, out of jealousy of his cousins' success in commerce, piety and fortune - while I remained a heretical teacher, begging to have my articles published in obscure journals.

The whole time, I remained silent, my eyes flitting around like a little rabbit, watching their faces. Each hideous face was followed by an even more repulsive one. But I wasn't afraid. On the contrary, I felt this strange excitement at the idea of unleashing one of my narrators on these faces to tear them apart.

I know them all. I know their secrets, their scandals. I know that what I know would be enough to flay them in a large text or dissect them one by one in small stories - depending on the mood and the whims of the writer.

The atmosphere was heating up. Each who spoke was louder than the last. But no-one dared to go into the details of what I had written; they were content to deny the whole story. My story - previously published, then withdrawn - was the omnipresent absentee of the meeting. It was obvious that they hadn't read it, but had heard about it. And that sent them back to a gnawing truth, a truth suspended in their minds, outside my text, that they all dreaded.

In reality, I'd written what they already knew, then added what they couldn't even imagine. I've always been convinced that there's no history without scandal. And that our scandals are our most explosive asset.

At that meeting, that inner hunger to write a new story opened wide before me. For they know what I know. And they know that others like me know what I know. But as soon as what we all know turns to ink on paper, they deny all knowledge.

I finally dared to ask a question:

- If what I've written is a lie, why are you angry? I didn't mention names or places. I wrote a story in the abstract. So why do you think I was talking about your grandparents?

Uncle Siddiq's face twisted - he'd thought the matter had been settled by accepting my written apology. But I was detonating a bomb, the consequences of which he might not be able to withstand. My question was so destabilising that I heard insults such as "son of a bitch", threats and intimidation. If it hadn't been for the presence of my uncle, all hell would have broken loose that afternoon.

I smiled slyly, then rephrased my question:

- Dear cousins, removing the text now- which I already did two days ago - and what you are now doing, even killing me (with this, I turned to the one with the tender face, whose eyes seemed to tremble) - won't do you any good. Even before you shoot me, the text will come out like a bullet. All your angry reactions will only prove that what I've written is true. That's why, as a cousin who cares about family as much as you do, I advise you to simply let it go.

Everyone was disoriented, and I felt that the kind-faced man had lost his power over me. Siddiq was watching their reactions like a train driver fearing that a careless child or a drunkard might cross the tracks. As for me, I was feeling the pleasure in writing again, and with this, I felt I was gradually regaining the upper hand.

I then threw another question at them, brimming with cleverly calculated naivety:

- Answer me honestly: have you read the text?

Uncle Siddiq started, as if he'd just felt a pain in his side:

- What do you mean?

- I simply mean: have you read the text? Have you read the whole thing, six or seven pages?

Uncle Siddiq turned to the group, then to me, and muttered:

- I haven't read it... And what does "published on sites" mean? I don't know about sites. I know about books, yellow ones and white ones.

No one answered. Clearly, his question served to buy them time to answer him, not me.

As he insisted on knowing what these sites were in order to divert attention from my question, one of those present explained that they were websites, similar to newspapers or magazines, except that you read from a screen instead of paper.

Uncle Siddiq nodded, pretending to understand, without taking his eyes off my face. He was looking for a way out of the trap I'd caught them in. My last question had seemed insignificant but was actually my winning card. If the answer was "no", I became a defendant without a crime; answering "yes" would draw them into more detail, and give me the opportunity to ask unexpected questions - all of which would provide material for my next story. I could feel the tail of my narrator-dog ready to devour the lame leg of the story.

I could feel the tail of my narrator-dog wagging, ready to pounce on the lame leg of the story.

After a silence, repeated threats, and the glances of Uncle Siddiq - which I noticed shifting from accusation to shy admiration - I said to them:

-You see well, my cousins, how wrongly you have accused me. Have you noticed, Uncle Siddiq, that they accuse me of a crime when they haven't even read the text?

- ...

When he sensed that my cold words had truly shaken them, Uncle Siddiq straightened his posture. It was clear that he was going to speak, to bring the conflict to an end, having perceived that the balance was tipping equally between the insults hurled and the fear felt. He was looking for a sensible way out.

- Listen, you youngsters, whatever happens, you're family, cousins. What I've heard about what that idiotic young man - your cousin - wrote should not serve as a pretext to reveal our secrets, nor should it give outsiders an opportunity to laugh at our family's glorious history... A history you unfortunately know far too little about.

- Personally, I need to know more. I've always had the feeling that my father didn't tell me everything, Uncle Siddiq.

He ignored me, adjusting his turban and placing it back on his head like an upturned pot.

- What you wrote about your aunt Umm al-Kheir and your grandfather Saleh is totally unfounded.

- And what did I write?

- Don't play the fool. You know very well what I'm talking about.

- I only wrote what my imagination dictated to me, what my mind constructed. This is not an attempt to dig up the family's past.

- I don't understand a word you're rambling on about, and I don't intend to dwell any longer on it.

The faces of my cousins expressed a fragile firmness, betrayed by their collective embarrassment.

- What I've heard is totally untrue.

- And what have you heard?

Uncle Siddiq noticed my smirk, and also that kindly face that threatened to burst like an overstuffed sack. He decided to put an end to the discussion once and for all:

- Listen to me and don't interrupt, and you too, listen to me carefully.

At that moment, I lit a cigarette and pulled the tea tray towards me to drop my ashes. The gesture was deliberately casual, but I wanted them to interpret it as arrogance, a provocation. Uncle Siddiq saw all this, but seemed in a hurry to get it over with before things got out of hand. He spoke plainly, staring at a point in front of him, not looking at anyone. He looked as if he were peering into a past whose weight he would like to escape.

- The story people have been spreading for years is a pack of lies about your grandmother Umm al-Kheir. And your grandfather Saleh was not the man you've been told he was. The late Hajj Saleh - may God have mercy on him - never committed adultery with the pious Hajja Umm al-Kheir.

My cousins' faces turned crimson, while I maintained a feigned expression of neutrality, so as not to break the thread of the tale Siddiq at last seemed ready to unwind. My inner dog was already sniffing out the clues to this new story.

- Your father, Hajj Mansour, is indeed the legitimate son of your grandfather, Hajj Tijani. But may God curse the one who was the cause of all these suspicions. I don't want to go into the details so as not to reopen wounds that died with the people who lived them. Uncle Siddiq glanced at me. This time, I was being targeted. I looked concentrated, moved, as if to encourage him to speak more.

- Hajj Saleh, you may know, was an attractive man. He lived under the same roof as his brother Tijani. They shared their meals, their daily lives... Only sleep separated their homes: each had his own room, as was customary in those days.

My cursed narrator - this dog - began to let his imagination run wild: an attractive young man, his sister-in-law, the heat of the desert, the harshness of life... I closed my eyes for a moment. Siddiq struck me with his cane and I was jolted from my reverie.

- What people don't know is that when Umm al-Kheir became pregnant, during her period of cravings and weaknesses, she became attached to Saleh. She looked at him morning and night, drew close to him, and as I told you, he was handsome, may God have mercy on him. But it was out of her control; the laws of pregnancy. When she gave birth to Abdullah, he looked a lot like his uncle Haji Saleh. But women, with their mischievous imagination, embroidered stories.

This mention of women's imaginative power struck me: I had never used a female narrator in my stories. Why not choose a female dog instead of a male for this particular story? A spark went off in my head. Then I returned to the uncle's voice.

- Young people, that's all they were... (he swallowed hard) and a whim of pregnancy. Yes, a pregnancy craving.* And God is my witness. God knows I've already said it to many, but it was embarrassing to say it to you. But you had to hear it from me. I thought silence would eventually dry up this wound like a sore knee... But wounds don't heal when you scratch them with your fingernails.

*In Arabic, الوحام is an important phase during a woman’s pregnancy in which she strictly refuses or eagerly desires food or other things. If she wanted something but didn’t get it, the shape of the object will be visible on the baby’s skin when it is born.

Uncle Siddiq wiped his face, as if to wash it clean of sweat and dust. I turned around: the faces had regained colour. My cigarette had gone out.

The friendly-faced one spoke:

- We must thank Uncle Siddiq for his courage and wisdom.

Then he turned to me:

- The solution is for you to add this detail to your story.

- What detail?

- The story of... Ah... the craving... yes, the craving. Very well.

I left without saying goodbye. Uncle Siddiq had waved me off. He didn't want to meet my eyes. I felt that great compromises often require a great lie.

At the door, a question from the devil himself landed in the nest of my head, and I turned to Uncle Siddiq as I slipped on my shoes:

- What puzzles me, uncle, is that this tic of spraying a little saliva while speaking is a well-known habit of my grandfather's, and inherited by my cousins... but not by my father, nor my brothers...

Uncle Siddiq had already turned to my cousins, ready to tell them what they wanted to hear. He received my question like a blow to the head. He shook his head, saw me standing in the doorway, straight as a post. Then he said in a calm, wise voice:

- I told you - it was because of the pregnancy cravings... That's right, you rascal. Just the pregnancy cravings.